The other day I had accidentally hit the strikethrough function in Microsoft Word and so as I was typing my carefully chosen words, they were simultaneously being crossed out. “Okay, I get it,” I said to my MacBook, irritated that my machine was mocking my toil.

Two of this summer’s group shows addressed the sense of futility I felt: Cancelled, Erased & Removed, at Sean Kelly Gallery, included works spanning 1960-2008 that took as their subject paradoxical instances when the opposing forces of making and unmaking, growing and disintegrating, presenting and concealing are inseparable. Meanwhile, a distinctive vein of humor in Marion Goodman Gallery’s Deep Comedy, which covered 1970-2008, was the absurdity of meaningless gestures.

The historical cornerstone of Cancelled, Erased & Removed was Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning (1953), in which the artist took an eraser to a drawing that the Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning had given him—thus the obliteration of one work gave birth to another. Knowing Rauschenberg’s plans, however, de Kooning challenged the younger artist by giving him the most heavily marked drawing he had, and indeed, Rauschenberg was not able to entirely rid the paper of its original image; faint traces of ink and crayon remain.

Fast forward half a century: in Mike Bidlo’s suite of 16 Erased de Kooning drawings (2005), one of which was up at Sean Kelly, Bidlo meticulously copied de Kooning’s drawings of women, photographed the replicas, erased his own work and then attached the photographed drawings to the backs of the their “originals.”

Rauschenberg’s act was art historically Oedipal: overtly hostile to Abstract Expressionism, the transformation of de Kooning’s dark drawing—via painstaking labor—to an essentially blank page signaled a revolt against AbsEx’s emphasis on universal expression, and the celebration of the unique painterly mark spilling forth from the tortured artist-genius.

Bidlo’s work is focused around a different, if related, set of issues—primarily the implications of appropriation. There are of course many ways to read this work, but one aspect of its meaning is that through its excess, Bidlo’s reprise pushes Rauschenberg’s gesture into the realm of the absurd. To spend endless hours mimicking the work of one artist (de Kooning) and to then un-do that work by mimicking the work of another artist (Rauschenberg) and to save the record of the original effort in a place where no one can see it (on the back of the erased drawing), is a colossal act of deadpan self-effacement.

Enter Deep Comedy. Curated by the artist Dan Graham with independent curator Silvia Chivaratanond, this exhibition brought together work that critiques social, political and artistic institutions through formal and conceptual strategies involving play and an inclination toward the absurd.

One of the strands within the show featured works that represented great amounts of energy being expended on pointless or fruitless activities, epitomized perhaps by Allen Ruppersberg’s Honey, I rearranged the collection (The Red and the Black) (2002). This poster-size silkscreened image of a fancy domestic interior is covered in Post-It Notes that offer desperate, funny, and poignant explanations of the work’s title: “Honey I rearranged the collection to separate works which seem to be about ideas from those which are truly splendid”; “Honey I rearranged the collection because that is all there is left to talk about”; “Honey I rearranged the collection but everything remained the same only more so.”

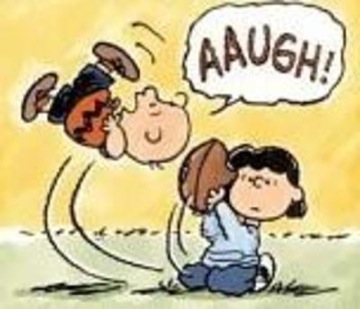

Humor is subjective, of course, but within the genre there is a lineage predicated on reaching too high, undertaking Sisyphusian tasks, and other acts that will most likely be wastes of energy ending in failure. When, against all odds, the underdog triumphs, we feel good; when he doesn’t, we’re supposed to think it’s funny. Lucy in the candy factory; Charlie Brown with his football; Corky St. Clair waiting for Guffman. What is it that’s so funny about futility?