British artist Steve McQueen’s current feature film, Hunger, has received pretty much universally positive reviews. Tracing the last six weeks of the life of Bobby Sands, the IRA hunger striker imprisoned in the Maze prison near Belfast in 1981, Hunger is a film that has sent journalists clamoring for synonyms for “harrowing” and “bleak.” The first notable thing about the publicity for the film is that his name isn’t suffixed by “not that Steve McQueen” on the posters dotted around the London Underground (he’s high profile enough not to need that). The second is that it forms part of what might be considered the wearing-down of barriers between mainstream cinema and video art.

The relationship between artists and the cinematic mainstream is one–until recently–with a relatively unsteady history. Cindy Sherman’s 1997 Office Killer was a campy extrapolation of the artist’s work in the 90s, all high-key color and shlocky gore. Larry Clark’s films, on the other hand (Kids, Bully, Ken Park) operate in symbiotic relationship with his photography, exploring similar territory of teenage sexuality and territorial awareness. They are defiantly outside the conventional Hollywood aesthetic, despite having undoubted influence on it. John Waters has similarly flickered between broad and narrow audiences, even featuring Cindy Sherman as herself in his joyous Pecker from 1998.

Video art itself has taken on an increasingly high-gloss approach over its short history. Bill Viola’s somewhat portentous video installations have harnessed the slick special effects of Spielbergian fantasy to hugely popular effect. And Rodney Graham’s brilliant deadpan films, like 1997’s Vexation Island, replay Hollywood cliché in its own cinematic vernacular, fusing Beckett and the historical epic in a hilarious and mesmerizing fashion.

Arguably, without Julian Schnabel’s unprecedented rise into mainstream cinematic culture with 2007’s The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, McQueen’s Hunger would have had difficulty finding a similar foothold. Schnabel’s widely acclaimed films have lent some retroactive luster to his critically frowned-upon smashed-plate paintings of the 1980s (Basquiat and Before Night Falls gathered critical steam before last year’s four Oscar nominations for Diving Bell).

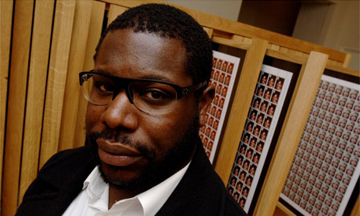

The commercial and critical success McQueen’s film seems to be garnering could have positive impact on his work too. Although an accomplished and widely-acclaimed artist in his own right (he was the 1999 winner of the Turner Prize and will represent Britain in the Venice Biennale next year), McQueen’s ongoing attempt to have his For Queen and Country project–postage stamps depicting British servicemen and women killed in Iraq–put into circulation by the Royal Mail has so far been turned down. The project, which has already gone on display in Manchester and London and is now heading to Edinburgh, is on par with his stark and unflinching vision in Hunger. Both are assertions of the need for political engagement in public discourse, and are explorations into relatively uncharted artistic territory; both cinema and art could gain from Hunger‘s success.