While the prospect of yet another Andy Warhol exhibition will be met by most gallery-goers with an indifferent shrug, Other Voices, Other Rooms, the new show at the Hayward Gallery, attempts to illuminate “lesser-known” aspects of the artist’s output–namely his forays into television, music production, filmmaking, album sleeve design and photography. The poster outside the gallery inventories the exhibition’s entire contents—well over 300 objects in total—in blaring neon caps. I defy anyone to read the legend for 33 Photobooth Photographs without feeling their will to live shrivel away.

Maybe it’s too cynical to extrapolate from the show’s paucity of well-known material an inability to secure significant loans (there are only five paintings). After all, the show trumpets its stone-turning analysis of the minutiae of the artist’s works on all of its advertising (“Think You Know Him? Think Again” teases the strapline on the posters, underneath a not-very-intriguing Polaroid self-portrait with a rubber skull) and claims to “shed new light” on an artist whose works seem to bounce between museums on a permanent basis. But the show itself–three large rooms whose curatorial conceits breathlessly make up for some very mediocre work (a star-spangled enclosure houses over forty individual TV screens showing his mind-numbing cable TV shows made between 1979 and 1987)–misses more than it hits, and is a reminder that greater exposure doesn’t necessarily mean greater understanding.

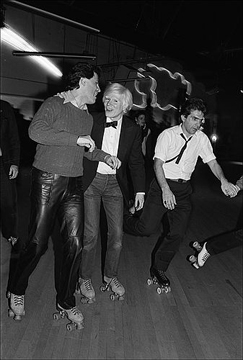

There are few artists with a stronger and more tenacious hold on the public imagination than Andy Warhol, but the more you see him (in mugs, t-shirts, mousemats, tattoos, interior design, greetings cards and, of course, Hollywood), the less you actually know him. His ubiquity has allowed myths to grow like mold on the surfaces of his paintings: Andy the camp Pied Piper, facetious and nasal, ready with an acid put-down; the user of losers. The everything-counts free-for-all of the exhibition implies a Midas touch that Warhol palpably didn’t possess. Any exhibition that features both a series of electric chair screenprints and a videoed performance of Duran Duran in their cocksure heyday can’t help but feel lopsided. The juxtaposition serves merely to limn the shape of Warhol’s visionary talents: at its best, his art is one of a finessed poise, leavened by a post-Surrealist acceptance of the happy accident–what Dave Hickey calls “exactly wrong.” The worst Warhols are a lapse in concentration, a falling-back on the haunches of his own myth; the best let things happen in an extremely concentrated, extremely controlled way.

Like Francis Bacon (whose retrospective happens to coincide at Tate Britain), Warhol’s public statements are a kind of pantomime narcissism some distance away from his real self. In both shows, biographical minutiae are given pride of place. By far the most popular room in the Bacon show is the display of minor ephemera–letters, scribblings, drawings, art books and photographs–that act like the preserved shinbones of saints in Catholic churches. In the Warhol show, the crowds around the glassed-in Time Capsule (scatterings of invites, letters and snapshots) were three people deep. Yet for all the media-friendliness of both artists, and their willingness to pad out articles with a juicy bit of misanthropy, they share a sensibility that is at once disinterested and profoundly moral. In their art, modern horror is framed in fields of affectless color, serialized and blanched of emotional meaning. And for both, the artist is a smokescreen for the art, a reflection in the glass of a screen or a painting.