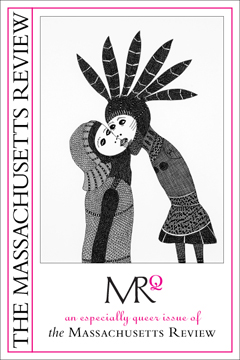

Recently, I was catching up on my reading and discovered a wonderful interview with Art21 artist Laylah Ali (Season 3) by Allan Isaac in the Spring/Summer 2008 edition of the Massachusetts Review. Filled with various insights about ways to “read” her images, the interview is essential reading for Art21 fans interested in Ali’s art.

Entitled “Here Comes the Kiss,” the interview discusses a number of her series including, Typology, Greenheads & Notes with Little Illustrations. Here is a snippet of the conversation that focuses on the riveting cover image, which is pictured above:

Allan Isaac: The Kiss and Other Warriors is reminiscent of the iconic Kiss by Gustav Klimt. Yours has the same concern with intricate patterns but your version is almost clinical emotionally. Did you actually have Klimt’s in mind at all?

Laylah Ali: I certainly thought about the title, and knew that his work would be an unavoidable reference, but I wasn’t really interested in commenting on his work. I knew my kiss wouldn’t be very romantic.

AI: Could you talk a bit about the Warriors part? A kiss comes into being at the moment of contact. Is the kiss being personified here as a violent figure?

LA: I think of the Kiss as a character — like a nickname for someone. “Here comes the Kiss” or “don’t mess with the Kiss — he will kill you.” I know it is open to other interpretations but that is my personal favorite. I think of the Kiss as a warrior.

Laylah Ali, Untitled, 2005, gouache on paper, 6.5 x 5 inches

Later in the interview she elaborates on how she thinks the art viewing experience is different from a personal encounter with a book:

AI: Could you explain the “performance of viewing”? How do you imagine the different viewing communities that form around the painting and around the book?

LA: When one goes into a gallery or museum to look at art, there are usually others around: viewers or guards, often security cameras as well. One perceives, actively or otherwise, other people viewing, and so I find that the reality of other people’s physical presences has to be reckoned with on some level. Also, the work itself is often given a rarefied or exalted status, even if it is a work that is trying to defy that exaltation. One has to negotiate the relationship of one’s own physical being with the work presented: Distance? Intimacy? Can you touch it? Is it a fast exchange, like a quick hello or something more like a kiss, where one gets very close and looks into the work, almost too close? This all can be part of the allure of seeing shows in person.

I think that the best works in such spaces take all of that into account and play with it. But that’s harder to do with paintings and drawings, which tend to be mindful of their boundaries. As for the book, one can minimize his or her physical presence. When I read, I often feel that I have no body, or that it is in a kind of hibernation as I read. Interactions with books can allow for an intensive privacy that can allow for a less guarded interaction — perhaps people are more vulnerable and open in that situation.

All text & image reprinted with permission from the artist and the Massachusetts Review. Back copies of the issue are available for purchase here.