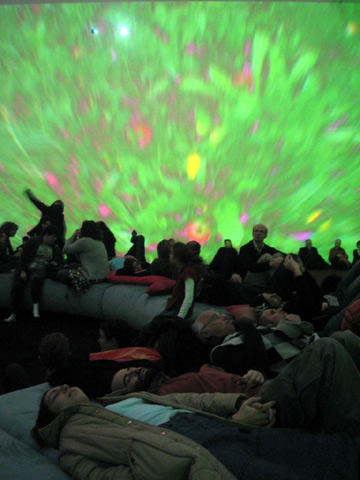

The ‘wow factor’ in Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist’s buzz-generating new video installation in the Museum of Modern Art’s atrium is huge. Featuring fields of flowers, Pour Your Body Out (7534 Cubic Meters) recalls MoMA’s ill conceived installation of Monet’s Water Lilies there four years ago. But while the towering space diminished Monet’s painting, memorably prompting critic Peter Schjeldahl to compare it to a “big, soiled Band-Aid,” the sullied beauty of Rist’s piece is deliberate; it has no problem commanding the area and overwhelming viewers.

Pour traffics in familiar clichés about the closeness of women to the natural world without adopting any particularly critical point of view. A modern-day Eve chomps apples and swims nude while lily pads, giant strawberries and other fruit bob around in the water. Watching her romp through a flower farm, caress an earthworm, and snap heads off flowers is sheer visual pleasure. Her lighthearted impersonation of a wild boar running through a grassy field is hilarious.

In a video produced by MoMA, Chief Curator of Media Klaus Biesenbach likens the site-specific piece to a pool in which the audience sits inundated by projected light. When the protagonist’s menstrual flow turns the waters blood red, the atrium takes on the aura of a womb or birthing pool. “You don’t need to be a feminist critic,” writes New York Times critic Karen Rosenberg, “…to understand the significance of a female artist unleashing a red torrent on MoMA’s immaculate white walls.”

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lL3NJdxfrAA&]

Like Doug Aitken’s video projection on MoMA’s exterior a few years ago, Rist’s piece is an attractive spectacle. But it also radically feminizes a normally cold and masculine space (Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk first installed there alongside Monet’s Water Lilies set the tone nicely), not only with its subject matter but with the gaudy drama of several stories of fuchsia colored drapes and a enormous circular couch that invites visitors to lounge, chat and even sleep. As children played and one visitor slipped into a tai-chi routine, the atrium didn’t seem so much feminized but humanized, recalling MoMA architect Yoshio Taniguchi’s guiding vision “…to create an ideal environment for the interaction of people and art.”

Pingback: Week 13: Relational Aesthetics: Real Recognize Real | Issues in the History of Photography