What if, instead of talking about what makes an artwork controversial, we focused on what makes an artwork difficult?

Difficulty has long functioned as a keyword in poetics and music criticism. Generally, when a literary critic identifies a poem as “difficult” she makes no value judgment; the word is used to describe the poem’s accessibility (not only in terms of comprehension, but in terms of pleasure as well). A poem can be hard to read—actively so—and still be very good, and very moving. A poem can also be “easy,” accessible, and also be formally elegant and deeply compelling. “Easy” poems are sometimes difficult, though, in that they can be so simple that they challenges our sense of what a poem is (William Carlos Williams wrote poems like this). Similarly, music can be difficult to play, and difficult to listen to—difficulty is part of music’s vocabulary. And, like poems, music can be incredibly simple in its structure and yet be very challenging for the audience (think: John Cage’s 4’33”).

What if, instead of focusing on what makes something controversial, we focused instead on this line between the simple and the difficult? What if we start a conversation about Tony Smith’s Die (1962), for example, with “What makes this hard to talk about?” and “What information do you need in order to ‘get’ this work?” Questions like these help us to understand what lies behind the controversy that certain works leave in their wake.

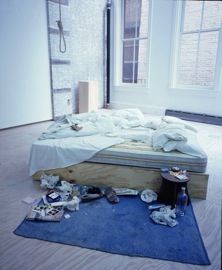

Tracey Emin, My Bed (1998) and Tony Smith, Die (1962)

For instance: like Smith’s Die, Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998) is controversial because it looks so simple—Emin’s viewers tend to ask “couldn’t I just exhibit my bed?” and wonder why it “counts” as “Art.” It can be grasped at a glance, but like Die, it also tells stories that can only be accessed via familiarity with its art historical context. Emin’s installation comments on how work by women artists will always be read as personal no matter what they do, so one might as well just exhibit one’s bed. It also, to a certain extent, cites Die. Smith’s six-foot sculpture deliberately recalls the dimensions of a coffin, and, like a coffin—or a bed—it seems to be waiting for a body (this made it famously challenging for Michael Fried, who found it more “theatrical” than “sculptural” and, for this reason, controversial). You can’t “get” that side of art like this without doing a little work yourself. Even the simplest works, in other words, often contain within them their own forms of difficulty.

Andy Warhol, Torso (Double) c. 1982

Andy Warhol loved controversy and made work that was labeled “obscene.” His Torso series openly flirts with pornographic convention. It isn’t formally difficult. It’s easy to figure out what’s going on, and it doesn’t demand that much from us—except in the way that it positions the viewer in a homoerotic relation to the image, which is a challenging experience for some. In that sense, its difficulty, and its controversial dimension, is specific to how the viewer feels about looking at the image.

We arrive at the following question: is simplicity itself what makes some work controversial?

Pingback: Crying Wolf | Art21 Blog