If the impact of Katrina now seems minimal in the rest of New Orleans, in the Lower Ninth Ward it was obviously devastating. My guide, who has since become a friend, explained to me that the fields all around were once as densely packed as the city’s other neighborhoods. That knowledge deeply impacted the way I looked at the art in the area.

It wasn’t surprising, then, that many artists decided to use the “home” as a basis for their art. Katherina Grosse chose to paint a home at 5418 Dauphine Street; Wangetchi Mutu “sketched” one out of wood at 540 Caffin Avenue; and Leandro Erlich erected a ladder which leans on a window in mid-air, hovering as if it was ripped from a wall.

Below are some of what I saw among the ruins of the Lower Ninth Ward. It’s not surprising that many of the works seem obsessed with standing witness to the injustices that the surrounding community faced.

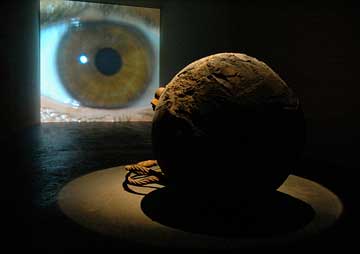

Janine Antoni (Season 2) T-E-A-R (2008)

The lead wrecking ball stands alone in front of a projected eye. The giant eye evokes the nightmare vision of George Orwell’s big brother (1984), where we are always being watched. But here the eye seems to have witnessed some form of destruction. The wrecking ball sits in a spotlight and echoes the shapes on the screen. I sensed the heavy burden that witnessing a tragedy can entail.

Ghada Amer, Happy Ever After (2005)

My guide told me that this piece was moved during the biennial and as a result the vines never grew up the trellises, which read, “Happy Ever After.”

Situated by the infamous levee that flooded the Lower Ninth Ward, when I sat on the round bench in the middle I could only imagine that if the vines had grown fully, the whole landscape would disappear, allowing me to imagine myself in a fantasy world of blue sky and greenery. Unfortunately like the promise of the Lower Ninth Ward, Amer’s piece was never fully realized in New Orleans, but it was a beautiful idea nonetheless.

\

Mark Bradford (Season 4), Mithra (2008)

Bradford’s epic sculpture never impressed me much in photographs,but in person, its scale and form were breathtaking and inspiring. A replica of Noah’s ark from the Bible’s Old Testament, it is manufactured out of wood and covered with advertisements that have since peeled and washed away. Moving around it you feel like you are confronting a relic from a bygone age. It dwarfs the surrounding homes and made me wonder about the nature of religious redemption.

Leandro Ehrlich, Too Late For Help (2008)

Rather literal in its meaning, Ehrlich’s piece was the most surrealist piece in the biennial. It was well situated in a swath of the city which resembled the empty surrealist landscapes of Yves Tanguy or the war-ravaged scenes of Paul Nash. Ehrlich’s work was poignant for the way it highlighted the bizarre emptiness all around.

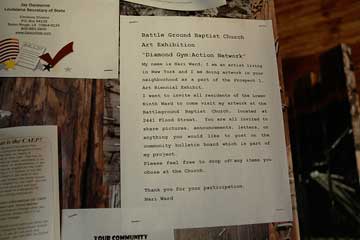

Nari Ward, Diamond Gym (2008)

Ward invited local residents to plaster the walls around his metal diamond with notices, notes, and random posters. As you walked into the space, you heard inspirational African American oratory, along with snippets of music. The notes and messages from the locals were fascinating to read. It was one of the only times at the biennial that the voices of the people who experienced the tragedy of the Lower Ninth Ward were able to seep through. Otherwise, the artwork itself felt somewhat hermeneutic, and I felt like there was a secret that wasn’t revealed to me. I kept wondering if I was the intended audience for the work.

Adam Cvijanovic, The Bayou (2008)

Cvijanovic’s wallpapered rooms were lavish and lush. They made me think about different notions of home, whether it was inferred by a landscape, a building or our general sense of place. Each room was plastered with these hand painted scenes that gave the space a feeling of uneasy calm. Fireplace mantles served as makeshift altars and some sections of the painted scenes were so abstract that they resembled the abstract paintings of Gerhard Richter more than a southern Bayou.

Wangechi Mutu, Mrs. Sarah’s House

Mutu “sketches” a home that was never built. It seemed to reference Venturi Scott Brown & Assoc.’s House of Benjamin Franklin (1976) with its simple linear frame, in that it resembled a dreamy vision rather than an actual place or thing.

Tomorrow: the French Quarter & Marigny.

Pingback: Talking with Janine Antoni, Part Two | Art21 Blog