I was surprised that Prospect.1 shied away from New Orleans’ infamous French District as much as it did. The epicenter of New Orleans’ global brand, and one of the world’s favorite Mardi Gras destinations, only one artist exhibited in the neighborhood.

Fortunately, there was art galore next door in the somewhat lesser known but equally historic Marigny neighborhood, which is also home to a significant chunk of the city’s arts community.

Another venue located at the crossroads of the French Quarter and the Marigny, the Old U.S. Mint Building, was not only one of the most impressive art venues but also filled with some of the most fascinating works of the whole biennial. Today, I offer you a small tour through this well-preserved part of the city.

Rosângela Rennó’s video work (2008)

Rennó was the only artist to exhibit in the French Quarter. Juxtaposing videos of white Cajuns and black Creoles, she attempted to offer us some insight into the cultural appropriation that is part of the cultural fabric of New Orleans and, by extension, Louisiana. Unfortunately, after asking around and doing some research, I discovered that the binary scenario (black/white, creole/cajun) that Rennó offered us in her video wasn’t all fact and partly fiction. Like all issues of cultural appropriation and hybrid cultures, the realities were far more complex than they first appear.

Srdjan Loncar, Value (2008) at the Old Mint Building

In light of the economic crisis, Loncar’s work was almost prescient. Visitors could buy a case full of Loncar’s notes (not real money) for $500. According to the security guard, the work was quite popular and dozens had already sold. Appropriately installed in the Old U.S. mint building, I wondered if Loncar was spoofing the American financial system or the biennial viewers themselves.

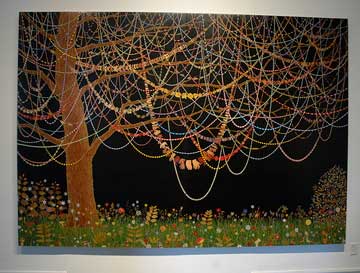

Fred Tomaselli, Hang Over (2005) at the Old Mint Building

Tomaselli’s paintings were fresh, lively and even hallucinatory in their details. Encased in resin, the artist collaged leaves, paper, pills and paint to create wondrous panels that feel like they were ripped out of an intergalactic children’s story book.

Zwelethu Mthethwa, both photographs titled, Untitled (from the Common Ground Series) (both 2008) at the Old Mint Building

These colorful photographs were formally beautiful, but the poor and squalid conditions they depicted tinged the scenes with a sense of sadness. At this scale you couldn’t help but notice the visual elements that give New Orleans homes their colorful and quirky character.

Cai Guo-Qiang (Season 3), Fireworks From Heaven (2008) in the Marigny

Cai’s massage chairs and “firework” displays were a favorite of many art tourists who welcomed the rest stop where they could receive a very intense (and automated) massage. When I got there one of the star bursts weren’t working but the effect was still quite impressive.

Jose Damasceno, Tabula Rasa (2008)

The artist fashioned a giant calculator made of chalk which was fittingly place in an old school building. In this context, it appeared like a monument to early education which is colored by the interplay of learning and childhood games, like hopscotch.

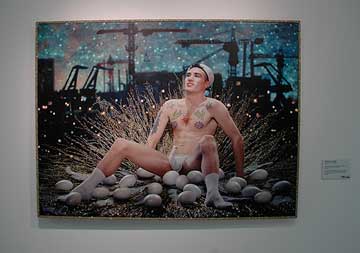

Pierre et Gilles Le Chant des Cygnes (2008)

Finding the art work of Pierre & Gilles in a police station in the Marigny was odd, but there is no denying that the French pair’s images celebrate a certain aesthetic that feels at home in New Orleans, which (particularly during Mardi Gras) can be simultaneously sensual, campy and decadent.

Amy Sillman, left: Orchard Portraits (2008) — Portraits of people involved in an alternative space on the Lower East Side of NYC from 2005 to 2008; right: After Chip (Abstracts) (2008)

Sillman’s portraits were some of the most sensitive works I encountered at Prospect.1. Located in one of the city’s leading school for the arts, the images celebrate anonymous members of a non-profit space that no one has ever heard of. The artist’s small tribute to some unsung heroes of the American arts community was a beautiful poem to those that sustain the richness of our culture, even if they don’t demand the spotlight for their work. Her drawings veered towards abstraction and their scale allowed them to remain intimate and very human.

Tomorrow, the Warehouse Arts District.