Holy neo-conceptualism! The Vatican has issued a press statement announcing that it will be participating in the Venice Biennale this summer, which will make this year’s event one of the most refreshingly strange ones in its 114-year history (British artist Liam Gillick will be representing Germany, while the Welsh pavilion will show work by national genius and founding Velvet Underground member John Cale). The Vatican claims to have been “inundated” with ideas from both artists and senior church figures in a move apparently designed to counter perceived artistic assaults on Catholicism. From the furore around Chris Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary during the Brooklyn iteration of the Sensation show in 1999, to last year’s kerfuffle over Martin Kippenberger’s crucified frog, displayed in Bolzano, Italy—in protest at which an Italian politician, Franz Pahl, went on hunger strike, describing the sculpture as “a grave offence to our Catholic population”—the Catholic church has taken more than its share of body blows in recent years. Nonetheless, there’s something undoubtedly amusing about the ease with which the Church takes offense at what are often cheap shots designed for maximum exposure, a sort of comic replaying of the tragic consequences of the controversy around the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons of 2005.

Christianity is an easy target for artistic outrage because it is so inextricably bound to the representational image. Throughout its history, the Church has had an uneasy time with representation, and for its first few hundred years artistic developments came hesitantly, haltingly. It’s worth noting that one of the first recorded representations of Christ’s crucifixion is itself a parody; scratched into a wall on Rome’s Palatine Hill, it shows a donkey-headed character on a cross being worshiped by a man, with the sarcastic inscription, “Alexamenos worships his god.” Even during the Renaissance, the high-water mark of Christian representation, controversy was commonplace. Criticism of his Last Judgement fresco in the Sistine Chapel in the 1530s led Michelangelo to depict his most outspoken critic, Biagio da Cesena, as the donkey-eared Minos, judge of the underworld, fat-bellied and engirdled by a python with its jaws clamped around his genitals. And while Caravaggio’s apparent use of a drowned prostitute as his model for the pre-Assumption Virgin Mary was (not surprisingly) rejected, almost all of his confrontational and unsettling works were not only accepted but embraced by the embattled Church of the Counter-Reformation. It remains startling to see his disturbing painting of the crucifixion of St Peter on the wall of the chapel for which it was commissioned, a frank image of a big man’s final indignity. The interpretative flexibility of the Bible is both its greatest strength and its greatest weakness; its persistence as iconographic resource for contemporary artists will continue as long as art is made, as will ever more literal and divisive interpretations of its texts.

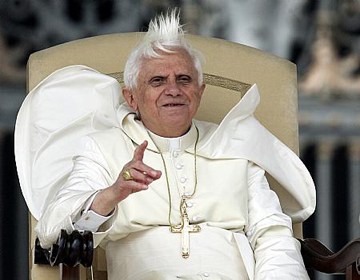

While the Vatican will have no national pavilion, it seems likely that the exhibition would occupy one of the city’s hundreds of churches in line with previous years (the baroque San Stae is used annually as an exhibition space). The question is: what kind of work will it show? While Christian imagery has its own significant presence within contemporary art (from Damien Hirst’s retellings of the lives of the saints in formaldehyde and livestock to Mark Wallinger’s channelling of Christian mysticism in his video and sculpture), it is rarely without provocation. The Vatican has always had a somewhat troubled relationship with modern art, tending to plump for a conservative abstracted realism, as seen in most modern Catholic churches; its last major commission for the basilica of St Peter’s were the bronze panels of the Door of Death by Giacomo Manzu in the late 1950s. The most obvious contender (mentioned in the press release alongside Anish Kapoor and Jannis Kounellis) is perhaps Bill Viola, whose portentous and relentlessly tasteful videos are very much in line with Catholic conservatism (and whose 2007 Venice show took place in the church of San Gallo). The press release, in its only specific description of the Vatican’s chosen works, enthuses about an “amazing” holographic projection of Pope Benedict XVI by French artist Yannig Guillevic. That whirring sound you hear is Michelangelo reaching escape velocity, somewhere far below.