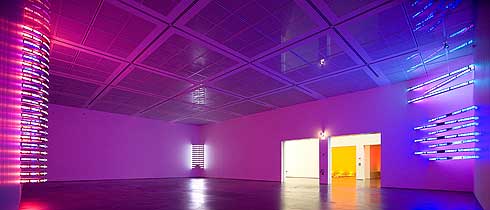

EXCLUSIVE: Jenny Holzer discusses the programming of her LED sculptures during the installation of the exhibition PROTECT PROTECT at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. Featured works include MONUMENT (2008), Thorax (2008), Purple (2008), Blue Cross (2008), Green Purple Cross (2008), and Hand (2008), among others. The exhibition remains on view in Chicago through February 1st, and will travel to the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York in March.

Whether questioning consumerist impulses, describing torture, or lamenting death and disease, Jenny Holzer’s use of language provokes a response in the viewer. While her subversive work often blends in among advertisements in public space, its arresting content violates expectations. Holzer’s texts—such as the aphorisms “abuse of power comes as no surprise” and “protect me from what I want”—have appeared on posters and condoms, and as electronic LED signs and projections of xenon light. Holzer’s recent use of text ranges from silk-screened paintings of declassified government memoranda detailing prisoner abuse, to poetry and prose in a 65-foot wide wall of light in the lobby of 7 World Trade Center, New York.

The exhibition PROTECT PROTECT is curated by Elizabeth Smith, James W. Alsdorf Chief Curator and Deputy Director for Programs at the MCA. In a two-part interview, Smith lends us her thoughts on the exhibition:

ART21: Jenny Holzer’s a fairly well-known contemporary artist, and yet it’s been a while since she’s had a major showing here in the U.S. How did that come to factor into your decision-making process behind the show?

ELIZABETH SMITH: It’s pretty amazing that Jenny Holzer’s work hasn’t been seen in a major museum in the United States in almost 20 years. She’s been showing in Europe quite extensively during the past few years, so we really feel like we are reintroducing her to the American audience. Especially because the show presents a lot of newer work that people haven’t seen. It’s a new Jenny Holzer, in many respects.

I think a lot of us who have followed her work, who are familiar with it, think about a certain type of work that she became known for — her LED signs, her benches — pieces that are somewhat smaller in scale. But with this current exhibition she presents a number of LED sculptures that are monumental in scale, that are architectural. She’s also presenting for the first time a body of silk-screened paintings that are based on declassified United States government documents.

It’s a good time for us to be showing Jenny’s work; not just because of the content, but because we are presenting a major figure at the midpoint of her career and showing that she’s moving in a different direction. I think that’s really important. I think it’s really brave for an artist to continue to develop and push the envelope with their work. In Jenny’s case, although she’s been moving into new media and new directions, I think what’s interesting to consider is the consistency of the messages within her work. She’s always dealt with issues surrounding abuses of power. And she’s always caused passive viewers to become active questioners, in terms of how they read and understand and react to the materials she presents. In that respect, it’s a very consistent show…but at the same time, it also shows us a new Jenny Holzer.

ART21: In the exhibition, there seems to be this emphasis on bodies or corporeality as a theme. Is that new in Holzer’s work?

SMITH: I think in this show those qualities are much more pronounced than ever before in her work. It’s really given her a chance to bring together a number of different references to the body. In the text that Jenny, herself, has written for a long time — particularly in the 1990s up until 2001— there has been an increasing emphasis on the body and on a first-person sort of human experience. I think that this really comes forward, too, in the text that she’s programmed into her current LED pieces that are from declassified documents. There are references to the body throughout those texts. The autopsy reports, for instance, give very stark and very chilling renditions of the trauma endured by individuals who have been killed as a result of the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Those references to the body are present throughout various texts in the exhibition.

But then also there’s this reference, sculpturally, that underscores that. You have that in some of the LEDs which are configured in a circular configuration reminiscent of a ribcage, for example. Or you have that in the images of hand prints taken from United States soldiers who were accused of war crimes. And then you have this bodily reference, presented very strongly, in a group of actual human bones that are laid out on old wooden tables. They’re chilling, sobering, and very startling, actual representations of the human body after death. So she has been able to interweave these different references — textually and sculptural, the object and the image, language and experience — in ways that all worked to intertwine and reinforce one another.

ART21: What were the challenges in putting together the exhibition?

SMITH: I think I was probably naïve going into the project — because I should have realized this — but I didn’t until we actually started to work together: Jenny is very precise about language. And so when I was writing my essay for the catalog, I did what I do usually when I work with an artist: I share an early draft with them of my thoughts. I usually use that as a way to have a discussion, a dialogue with them back and forth about, about how to further develop the argument.

In this case, I wished I hadn’t done that. I should have given Jenny a much more polished, final version, because she’s incredibly precise about everything. So in retrospect, it took me a really long time to get my essay right, but it also did engender a really great back-and-forth between the two of us. Jenny really wanted to clarify a lot of the points that I was addressing rather cavalierly. So that was one interesting challenge. (LAUGHS)

Another challenge, of course, is the technology of her work. We are so dependent on programmers and fabricators and individuals from outside what is customarily considered “the art world” to make sure that the pieces are right and functioning well, especially because some of the works are new and are being made here on site. A large team of people has to be involved with the production of the works. That’s an area that’s not my forte. I’m more about content, not so much about the technique or technology. So it really has to be a team effort, but that’s actually a good challenge.

ART21: Do feel like any of the works in the exhibition date themselves, by virtue of the period when the text was either written or appropriated? Or do the texts have a more timeless quality for you?

SMITH: Several pieces in the exhibition are new works that are programmed with older texts. It’s very interesting to read these texts and to think about them in relationship to the newer information that you find in the exhibition. I think there is a real resonance.

We can read a lot of the statements that Jenny wrote earlier in a way that underscores how current they still are, especially her series of texts called Inflammatory Essays (1979-82). Those were based on or inspired by her readings of manifestos by political figures, ranging from Mao Zedong to Vladimir Lenin and many others. She adopted the same kind of incendiary tone in those readings that appear almost hysterical and hyperbolic. When we think about the rhetoric, it’s so apparent and just everywhere in our country today — particularly at this moment, so near to a presidential election. It’s very interesting to relate or to think about her earlier words from the perspective of today. They seem very current and very fresh.

ART21: Do you ever find the references to violence in the work off-putting? What do you find redeeming about art that tackles such serious subject matter?

SMITH: Some of the content is certainly scary, and it’s horrifying. If you really take in what is said in some of the pieces that she presents — it scares you to death. You can’t believe how people can do these things to one another. But yet, that’s what’s recurred throughout human history. When you consider very recent occurrences in the world, like the current violence in the Congo, it is just absolutely excruciating. It sounds, to me, even more traumatic than what went on in the former Yugoslavia and elsewhere. I think it’s really scary and it makes you question human nature.

I think what Jenny’s demonstrating is that the concerns she’s dealing with now are not new in her work. She has always concerned herself with challenging abuses of power and with presenting different points of view about a subject and highlighting the confusion that surrounds us in the world today. To my mind, her work succeeds so well on the level of presenting or revealing uncertainties rather than truths. And I think that the way she causes us to reflect on these uncertainties is really powerful for us as viewers and as citizens.

PHOTOS | Jenny Holzer (from top to bottom) MONUMENT, 2008; Thorax, 2008. Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica; Blue Cross, 2008; The David Roberts Collection, London; Green Purple Cross, 2008; For Chicago, 2008. Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago. Photo: Lili Holzer-Glier. | MONUMENT, 2008. Text: Truisms, 1977-79 and Inflammatory Essays, 1979-82. © 2008 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Vassilij Gureev. | Left Hand (Palm Rolled), 2007. Text: U.S. government document; Right Hand (Palm Rolled), 2007. Text: U.S. government document; PALM, FINGERS & FINGERTIPS 000406, 2007. Text: U.S. government document; PALM, FINGERS & FINGERTIPS 000407, 2007. Text: U.S. government document. | Blue Cross, 2008. David Roberts Collection, London. Photo: Lili Holzer-Glier. | All works © 2008 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

VIDEO | Producer: Wesley Miller, Nick Ravich & Kelly Shindler. Interview: Susan Sollins. Camera & Sound: George Monteleone & Alexander Stewart. Editor: Jenny Chiurco. Artwork Courtesy: Jenny Holzer. Special Thanks: MCA Chicago & Karla Loring.