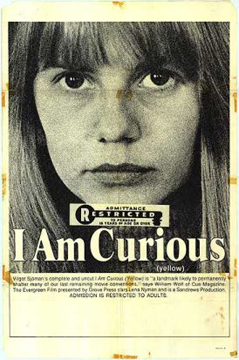

Vilgot Sjöman's "I Am Curious (Yellow)," (1967)

I’m also teaching a course at the École Régionale des Beaux-arts de Nantes called, “Workshop: I am curious… (The Artist as Ethnographer).” Each Friday morning, my students and I have made a regular practice of going to a place, talking with strangers, and asking questions. I’ve gathered a few notes on my research for the course, what we’ve done, and what we’ve discussed.

The title of the workshop is based on the films of Swedish director, Vilgot Sjöman, I Am Curious (Yellow) (1967) and I Am Curious (Blue) (1968), both documentaries-within-films. In the opening scenes of I Am Curious (Yellow), Lena surveys passersby, microphone in hand, asking the question, “Do you believe Sweden has a class system?” Later, we see the director and his camera crew filming the documentary, but it is Lena’s intense curious energy that drives the film.

Another source of inspiration for the course was Hal Foster’s essay, “The Artist as Ethnographer” [in The Return of the Real: Art and Theory at the End of the Century (October Books, 1996)]. I have the vague suspicion that we may actually be performing the faux alterity or “outsideness” that he criticizes in applications of pseudo-ethnographic models in contemporary art practice. But sometimes you have to do wrong before you learn how to do right.

Artist Harrell Fletcher wrote a text called “Some Thoughts About Art and Education” (2007) based on his artistic practice and experience as a teacher. His observations about experiential education, the classroom environment, project research, and going on field trips, have influenced the way I approach teaching. For example, he writes:

Collective Learning

I teach at Portland State University in Portland, Oregon, and I have a class currently where we started by having all of the students tell their life stories to everyone else. It took three classes to get through them all, but they revealed many interesting things that wouldn’t come out in more cursory introductions. Based on connections the students had we organized a series of field trips to places like a Veterans hospital, an alternative kindergarten, a campus fraternity, a high school geometry class, a Native American community center, a radio station, etc. From those experiences the students broke off into groups to develop projects like a radio show about grandmothers, and a lecture series in the frat house living room. Some of the field trips didn’t develop into projects, but were still valued as experiences. I like to think of this method as a way to lessen my role as the authority in the classroom and instead we share that role and all become collective learners.

On the first day of the workshop, I asked the students to tell me about their experience of the city of Nantes and the art school. They said that despite the school’s location in the heart of the town center, they felt isolated both from the public of Nantes as well as students from other universities. In France, college students typically focus on their area of study exclusively (e.g. law, biology, history) and that often determines their social circle.

Motivated by our conversation, we took a fieldtrip to the campus of the nearby Université de Nantes Faculté de Sciences et Techniques, the science and technical campus of the University of Nantes. One of the students said that they felt like tourists. By making the place “strange,” we were self-conscious of our role as outside observers. We noted that most of the students and faculty were walking briskly in the opposite direction as us, heading to the tramway for their lunch break.

One of the students became the de facto interviewer based on her outgoing personality and ease with approaching strangers. We approached a few young men hanging out by the entrance of the Resto Universitaire (cafeteria), who turned out to be students from the local lycée (high school) who come to the college campus to eat because they have trouble finding seats in their own cafeteria. We learned more about the university culture from a biology student and a mathematics student who were also waiting for the cafeteria to open. It was a modest exchange, but a step in the right direction.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GTwoO8fEzQo]

The following week, a Grève Générale (general strike) took place in Nantes and across the nation in response to President Sarkozy’s planned policies of job reduction in the civil sector, budget cuts in education, and other proposals for increased privatization in France. Tens of thousands of people from different constituencies (unions, teachers, students, civil servants, hospital staff, and others) gathered for a demonstration and march in the city center.

Our workshop took place the day after the general strike. We discussed whether everything goes back to normal the day after a protest. This question is particularly relevant now because the French government has grown increasingly numb to the time-honored tradition of protest since its apotheosis in May 1968.

We took a field trip to the Préfecture, which is the main bureaucratic administrative office in the city of Nantes. People go there to apply for licenses and registration (e.g. for vehicles and hunting weapons), to register farm equipment, to seek asylum status, to process immigration and citizenship, etc. Basically, if you’re going to the Préfecture, you are going for a very specific reason. My students and I, on the other hand, went there with the intention to observe about the site and learn about the people who work there.

In the lobby, the waiting area was full of people who had been or would be waiting a long time for their number to be called. Their faces were expressionless and tension hung in the air. We decided to venture upstairs to find out about the other departments of the Préfecture. Compared to the waiting crowds downstairs, the upper levels were eerily quiet. The hallways were lined with closed doors with frosted glass windows and a sign indicating the function of the office.

We came across a sign that read “Éloignement,” which roughly translates to “remoteness” or “distance.” We weren’t sure what that meant exactly, so one of the students knocked on the door of the office. A woman opened the door and skeptically looked at the four of us and asked, “What do you want?”

(to be continued in my next post…)

Pingback: Notes on a workshop (Part 2) | Art21 Blog