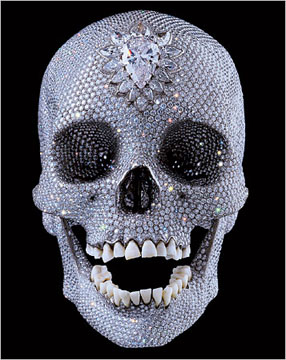

Damien Hirst, "For the Love of God," 2007. Platinum, diamonds, and human teeth.

In 2007, artist Damien Hirst exhibited a work at the White Cube gallery in London which is reputed to be the most expensive contemporary artwork ever made. Entitled For the Love of God, apparently in response to a question posed by the artist’s mother (“For the love of God, what are you going to do next?”), the work consists of 8,601 of the world’s finest diamonds encrusting the platinum cast of a human skull from the mid-1800s, complete with the skull’s original real human teeth. Financed by means of an investment of $28 million of the artist’s own money the work is reputed to have sold for $100 million, paid in cash. The artist contracted with Bond Street gem dealer Bentley & Skinner in order to acquire the collection of fine diamonds on the international market, which steadily pushed up the precious commodity’s price globally over the months of acquisition.

Inspired by Aztec turquoise mosaic skulls held in the collection of the British Museum, Hirst thought it would be great to create a diamond version, but was originally deterred by the prohibitive cost. Upon further consideration, he decided that the ludicrous expense could actually be the work’s rationale: “maybe that’s why it is a good thing to do. Death is such a heavy subject, it would be good to make something that laughed in the face of it.” This idea of laughing in the face of death resonates with the artist’s belief in the value of art collecting as something that can confer a certain kind of immortality: “I don’t see what else you can spend your money on. If you want to own things, art is a pretty good bet. Buy art, build a museum, put your name on it, let people in for free. That’s as close as you can get to immortality.” When asked to think about the work in relationship to the current controversy over African blood diamonds, Hirst declined, but did comment on the deadly potential of the object as an extreme luxury item: “That’s when you stop laughing. You might have created something that people might die because of. I guess I felt like Oppenheimer or something. What have I done? Because it’s going to need high security all its life.”

Apart from the obvious gossipy interest that this work inspires, For the Love of God provides an illustrative case study for thinking about art and value. While Hirst suggests that a certain kind of immortality may be attained by the art collector who acquires unique commodities and pulls them permanently out of circulation or makes them available for public use, Karl Marx suggests that the only immortality is held by the ways in which capital is endlessly transforming money into commodities (in this case, artworks) and back again. In For the Love of God, we can see capital’s maintenance of itself in the artwork’s surrender to circulation and indifference to form when it comes to its place in the market. Almost by a certain alchemy, formaldehyde soaked sharks and dead butterflies are transformed into expertly cut diamonds. For the Love of God has the simultaneous status of money itself (diamonds being one of the objects that expresses exchange value more perfectly than others), and of a product which is constituted by objectified labor in the form of raw material and labor as an instrument of the artist’s goals. Inasmuch as living labor is used as both a raw material and an instrument of labor in the mining of diamonds, this action works as evidence, to quote Marx, “that the capitalist desires nothing more than that the worker should expend his dosages of life power as much as possible without interruption.” Human life is a raw material in the construction of this artwork, not only in the form of the actual skull which provides its mold, but more importantly in the expenditure of life power in the often deadly process of mine working and in death resulting from armed conflict financed by the diamond trade.

Santiago Sierra, "250cm Line Tattooed on Six Paid People," 1999. Black and white photograph.

If Damien Hirst’s work incidentally acts to show us the machinations of capital in the interest of giving us an extreme example of the product of objectified labor, the work of artist Santiago Sierra intentionally uses the power of capital to harness living labor. While Hirst’s work makes no pretension of acting as a form of institutional critique, Sierra’s purports to reframe capitalist activity within the symbolic confines of the gallery in order to offer it up for analysis and criticism. One of Sierra’s most well known works is a performance project from 1999 entitled 250cm Line Tattooed on Six Paid People. Each of the unemployed men who participated was paid $30 to have a line permanently tattooed on his back. Sierra’s work presents us with the live act of the transformation of the worker’s living labor, or bodily and energetic potential capacity to work, into use value for capital. In this case, the use value of the worker is set in motion by capital in the specific scene of the art gallery—the worker mobilized as a raw material, as labor in the moment of objectifying transformation, and in that action as the art object itself. What is most striking is perhaps the worker’s absolute indifference to the specificity of his labor, which is in fact what separates and distinguishes the worker from the capitalist (or in this case, the artist). This is not the transformative decision-making process of the capitalist, nor the interested craft of the artistan or jeweler or even tattoo artist, but the bare exchange of time, energy and bodily integrity for a wage.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=naoYNgnDUl8]

What most disturbs me in viewing 250cm Line Tattooed on Six Paid People is not the difference between what the workers are paid and what Sierra will sell photographs of the action for, nor even the fact that human flesh is being used as a drawing surface, although both these factors are enough to give pause; it is rather the uniqueness and finality of what is being sold in an “indifferent” exchange. This is not simply the laborer acting is an instrument, but in fact a prime example of the laborer’s live body acting as a raw material which is used up in the objectification of labor. Of course this sort of thing happens all the time, only not in such an aestheticized, minimalist form. Bodies are deformed by factory work, laborers are afflicted by cancers of the lung, accidents etc. Sierra’s performance makes the finality of such an exchange exquisitely visible, although the use value of the worker’s body in this exchange is precisely in the mobilization of an idea which is the real substance of the product.

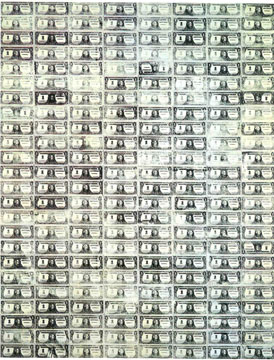

Andy Warhol, "192 One Dollar Bills," 1962.

This post wouldn’t be complete without at least a brief discussion of my favorite artist/capitalist, Andy Warhol. Warhol’s body of work perhaps most expertly demonstrates the absolute indifference of capital to the commodity or money forms it embodies and discards in turn. Soup cans, dollar bills, celebrity portraits, shoes, gold leaf, disasters, diamond dust, piss; capital is as indifferent to these commodity forms as the industrial image-making process of silkscreen is to the iconography set in place by its distribution of ink. Of course every aspect of Warhol’s practice at least nominally took on the form of a capitalist enterprise, from “factory” production to the embrace of mass forms ranging from Coca-Cola to Marilyn Monroe. Let’s stop and consider one of his more charming suggestions: “I like money on the wall. Say you were going to buy a $200,000 painting. I think you should take that money, tie it up and hang it on the wall. Then when someone visited you, the first thing they would see is the money on the wall.”

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aMtY5aFyShg]

Pingback: Bad Blogger « Freese

Pingback: Essay – Damien Hirst I Love You « artreviewed

Pingback: For the Love of Art: Desire Production | Examining External Influences and Artistic Contemporaries – ATMA & Funomena