Pilar Tena and Ilana Percher, "Jell-O Bog," 2007

In the fine art world, the story of the thing is the stuff comprising the thing. Paint, bronze, steel, video, screenprinting, mud, written language—the work is about the medium. And it’s also about another medium, its cultural context—movies, comic books, advertising, written language, or the art gallery itself.

But the point of a piece of art is primarily its social role, rather than some physical or symbolic essence. Melting into its environment, its audience, and its constituent pigments, the modern artwork tries both to command and to disappear, leaving us with volitional interrogation, an expensive insistence of excess matter. In doing so, it comes to represent another medium—a medium of exchange.

In a market society, art’s function, content, and exchange-value are all connected by the idea of excess. Art, like the rest of us, announces its place in the world in predominantly economic terms. In the dreams and desires of the unconscious mind, as in an unfettered free market, boundaries are meaningless, and enough is never enough. As we consume and produce, the excess currency—the profit we create—is another form of what is left over when we consume. Depending on how you take “consume,” this could mean sacralized cultural fetishism. Or, on the other hand, excrement. Either way, we long to contain it or to manipulate it.

The ephemeral abstractions of high finance and the primeval repugnance and joy in bodily processes are joined in modern visual art—a talisman to the sublime force of individual will (will being a faculty, sayeth Freud, that we discover during the period we learn to control our bowels). While visual art remains far from the mainstream, mostly by choice, it is in some sense the most dramatic result of humanism, the ideological bedrock supporting the motivational matrix of our society commonly known as capitalism. A visual icon—like a flag, religious symbol, or work of art—is a deeply affecting “interpellation,” a term coined by Louis Althusser for an ideological signifier that hails me and to which I respond. It addresses me like my own face in the mirror, without any acknowledgment of the assumptions and connotations of the icon. Artwork in the last century has teased out many of the implications of the current core dogma of the First World. which I sum up below in three motifs: autonomy, transparency, and the new man.

Jacques-Louis David, "Patrocle," 1780

Autonomy, the principle of individual freedom that insists on choice and rejects interpellation, is the hallmark of the commercial gallery, as well as the classical avant-garde. The artwork reveals the anointed maker in a way that words never could, in the retentive tableaux of Jacques-Louis David’s paintings, or in the explosive cartography of Jackson Pollock. The writings of Clement Greenberg and Dave Hickey offer lengthy modernist apologies for having anything at all to say about these ineffable things, whose solipsism admits no error. Purity is the only experience, and the market frequently rewards this work. The anal retentivity that Freud associates with the miser can simply replace one unspeakable medium of exchange with another. Damien Hirst’s preserved animals, much like the gleeful food-based artwork of Surrealist sculptor Meret Oppenheim, depict a closed statement, decay forever suspended, echoing the food-smeared African idols that have served as touchstones of authenticity since the height of European imperialism.

Piero Manzoni, "Merde d'artista (Artist's shit no.066)," 1961

Transparency connects art to writing, but in modern times has rejected interpretation, or any other form of exegesis whose gaze turns away from the hideous fascination of the Thing itself. This oracular reading is enunciated in the symbolism of the cultural and pedagogical institution. Rosalind Krauss and Susan Sontag are noteworthy haruspices of this post-war tendency, in which images and words are allowed to taint one another as multiple expressions of a single perception, and art starts to attempt depicting the conditions of its own legibility—often using empty spaces and vast grids. National Endowment for the Arts culture-wars martyr Andres Serrano has been displaying closeup photos of stool as signifiers, much in the same way Wim Delvoye created a defecation machine, Piero Manzoni canned his offal for sale, and Marcel Duchamp anointed a urinal as artwork—all in self-aware gestures that try to realize our alchemical dream of turning filth to gold.

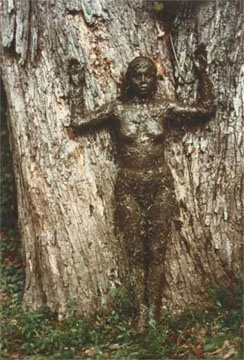

Ana Mendieta, "Arbol de la Vida (Tree of Life)," from "Silueta" series, 1976

Monumental and grandiose, followers of the new man are the most future-directed and mystical of the humanist avatars. These are the would-be poets of matter, artists who make events and accumulations that, even if they eventually shown in an aesthetically anesthetized space, never seem like more than withered leavings. These artists rely more on the body as a thing than the thing as an idea. The invasive and gooey performances of the Viennese Actionists, Carolee Schneemann, Kim Jones, Ana Mendieta, Chris Ofili, and Paul McCarthy hold out apocalyptic hope for some kind of cathartic expulsion of themselves, in which advanced technology and retail venues can be abandoned in favor of independent spaces in warehouses, vacant lots, abandoned oil rigs, you name it, where they can theatrically disappear into their piles of decay. The esoteric origin myths of Martin Heidegger have everything to do with this quest for protean perfection. Perhaps the patron imp of these artists is Joseph Beuys who, despite his dabblings in alchemy, almost certainly viewed his task as sublimation for spiritual power rather than worldly gain.

Nonetheless, the worth of a piece of artwork is primarily measured by what price it can fetch. This price is measured in part by the general popularity of art as an acquisition or investment, the piece’s materials, attractiveness (design and craftsmanship), and the value, if any, of its practical physical utility (I see no reason to assume that utility inherently negates artistic value, though there is conflict). But bolstering all those things, what makes it art is a quality that isn’t quite invisible but certainly ephemeral. That quality could be called cultural capital, it could be called reputation, or it could just be called taste. The artist is reputable and tasteful not because she is famous, but she becomes famous through presenting herself as reputable and tasteful. The object acquires its “aura” not exactly through uniqueness, as Walter Benjamin argues, but through interpellating eloquence, the artwork’s esoteric announcement of a transcendent and awe-inspiring free will, a foggy endless sea on whose shore all we slackjawed acolytes stand.

But is this ocean within a utopia of actualization or (as in Chester Brown’s Ed the Happy Clown) a hell of infinite shame and unquenchable hunger, opposing the endless bounty outside ourselves, a bounty that we both befoul and expand with everything we do? Mark 7:15 states, ”There is nothing outside the man which can defile him if it goes into him; but the things which proceed out of the man are what defile the man.” We are measuring our excrescence with excrescence, which culture can only unsettle with great difficulty. Caricature artist, tenured videographer, ironic hacker, rural ceramicist…everyone poops. There is no purity in the art market, the market of money exchanges, or the market of images and concepts. If money and art can do anything good together, it is to occasionally interfere with the way the other calculates value, and to confuse the yawning chasm of desire, for at least a moment. Thereby we may be able to value our freedom and our subjectivity, individually and collectively, as something more precious than public proficiency or personal self-esteem.

Bert Stabler writes about art for the Chicago Reader and Proximity Magazine, teaches high school art, and curates group shows. He began his explorations of primal muck with the show Brown River that he curated in 2007 (see Jell-O Bog above). $(heart), the little print exhibit that he curated with Paul Nudd for last month’s Version festival, commented on the art market via these equivalences. Bert lives and works in Chicago.