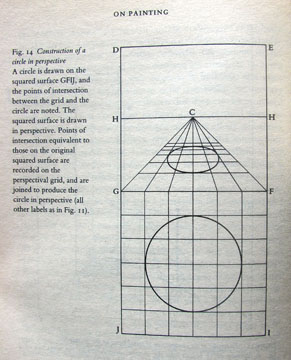

Fig. 14 of Leon Battista Alberti, "On Painting," page 70. Penguin Books, 1991.

I’m a PC, and I’m about to become a Mac. How is it that in this world of Al Gore-invented internet, Steve Jobs-overlorded life 2.0 and tweeting Twitter twits I can actually have a whole day of work completely undone by a single, cantankerous, God-forsaken PC? I swear, today was a good day and it’s been nearly two hours since I switched the thing on, and it only just now stopped making that quick, field of crickets clicking noise that all PCs make when they are deciding whether or not to continue living. It’s not even a Vista machine and I’m able to make and eat breakfast before IE and iTunes decide which is going to rule the roost for the day. IE: 2, iTunes: 0. Yesterday’s shenanigans lasted until 2pm, at which point I thought it would be satisfying to plug in my new government assisted and subsidized digital converter box. All that did was make it impossible to watch the DVD player. Turns out that the box makes your tv compatible with the new signal but the box isn’t necessarily compatible with the old antenna. Technology: 2, Adrian: 0.

So, the dog ate my homework, which I why I didn’t write anything the last few days. Plus, I was struck by an epidemic of mid-week, rainy day malaise, offset by the certainty that if I wrote about the baseball game that I went to Monday night, I’d lose some people’s attention. It did, however, get me to thinking about Fantasy, the theme of the moment for Flash Points.

Now, believe me, I don’t like baseball one bit, at least since Billy Martin retired. But I am constantly amazed at the way in which going to a game at the stadium, during which I not only had a big beer in a big plastic cup (non-commemorative), an absolutely excessive hot dog (with ketchup, mustard, kraut, and relish), and soft-serve ice cream in a plastic baseball helmet (Houston Astros? I thought they were supposed to be home team helmets. We’re not even in Houston.), I found myself in the most profound state of bliss since early last week. It’s such a stereotype. Americans at a baseball game—night game, weather clear, about 80/mid-20s for the Celcioids—drinking beer, eating excessively, piddling away time and money, eyeballs-deep in an economic collapse. Nero, loan me your fiddle. It was fantastic, fantastical, one of the most, nostalgia-laden, Hallmark card-worthy, saccharine moments anyone might ever have. One of those peculiar instances where fantasy and reality collide, much to everyone’s surprise and enjoyment. Reminds me of the passage in Mad Love when Breton finds the spoon with the slipper at the end. Hardly, but I love that sensation. That glint of the unheimlich, like in a Gregor Schneider haus, when it’s just strange enough. You know, been here before, I think I’ve seen this somewhere. Why can’t I remember?

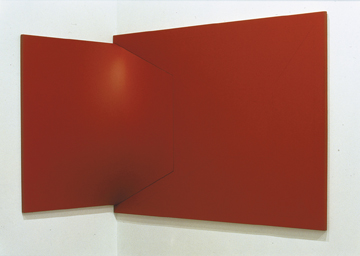

Enrico Castellani, "Superficie rosa," 1963. Acrylic on canvas, 130x92x21 cm (possibly mislabelled). Courtesy Haunch of Venison.

Which brings me to Enrico Castellani. I don’t know the time-space rules on a blog, but I want to go way back in the past, to May, which was before June’s Biennale opening, so I suspect May doesn’t matter anymore? That was, like, OMG, so last Biennale ago. Anyway, back when the dinosaurs ruled the earth, I went to see the Castellani show at Haunch of Venison, way above midtown. I’ve known about Castellani’s work for a while, mainly because I’m obsessed with 1960s Italian painting and what it does to space. Lucio Fontana gets the most press, and probably rightfully so, but Emilio Vedova and Agostino Bonalumi certainly deserve as much attention. I can hear all my friends groaning. Castellani is the fourth Beatle.

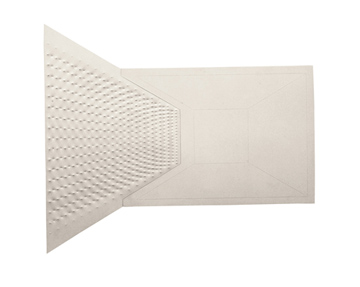

What really struck me about this show, other than its absolute magnificence, was how traditional it looked, old even. Albertian. The two works that really did it for me were two 1963 paintings, both listed as Superficie rosa, though the one is more bianca than rosa to me. I would know if I would have bought the catalog. Big mistake. The white one might as well be a diagram from Alberti’s On Painting. I have the 1991 Penguin Classics edition. Look at figures 6, 8-11, 13, 14 and try to tell me that Castellani isn’t going back to basics. He’s making leaps here as well. Superficie rosa—the red one—is even more interesting because it bends the corner. Castellani’s nails are gone, but the lines created by the join of the two canvases, what was reinforced by a drawn perspectival space in the white one, is now mediated by an actual, real-space bend. Albertian perspective, as actualized in a picture, at least at one point, presumed one flat field of vision at a time. A painting, that we’re standing in front of, on a perpendicular, looking at. Castellani has shifted this, elaborated it on two planes. The point, the vanishing point, what was supposed to be a nearly invisible point in the infinite distance has been transmogrified into one point among the infinity of others that make up the line that is the bend of the wall, the corner. Alberti has been multiplied outward and what should be our Albertian point of reference, where the canvases join, is offset, one among many. Maybe it’s not that exciting, that painting went from flat to spatial through the mechanism of spatializing flatness. Check out figure 14 again, and think about the line from G to F, the bend in the image. Maybe this is the ultimate tautology, but it makes sense. It makes sense that an Italian painter working at the end of painting as it had been since Alberti is using Albertian principles, not against themselves, but beyond themselves, to transcend painting. To keep it as painting, but still more than painting.

Enrico Castellani, "Superficie rosa," 1963. Acrylic on canvas, 130x92x21 cm (probably mislabelled). Courtesy Haunch of Venison.

Somewhere in there is a life lesson for me, that I keep telling myself so that I don’t forget it. Now, I wouldn’t follow half of my own advice, but I love those moments when I’m reminded how deep the history of art is, how long the memory of an artist can be, how negligent it is to look at anything in a vacuum. Remember that game Memory? It’s like flipping two tiles over. Castellani, Castellani…where’s the other Castellani…there it is, the Alberti.