As an homage to the recurring 36 Hours feature that frequently appears in the New York Times travel section, I have broken down hour by hour a recent perfect weekend at my new happiest place on earth:

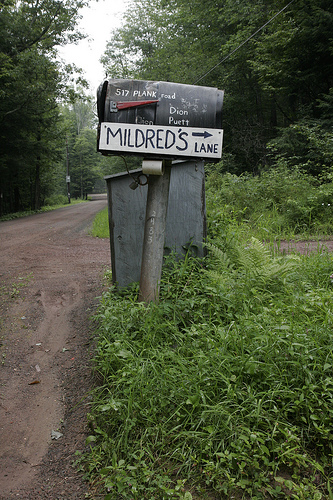

Welcome. Photo courtesy of Rebecca Fuller.

Running late for the four o’clock tour of Mildred’s Lane Historical Society grounds, I quickly made a left onto the red dirt driveway, which wound and curved around the rolling woodlands of the Delaware River Valley in upper Pennsylvania. As cell phone reception became a thing of the past, the drive opened up into a clearing on the 96-acre campus that contained an old barn, a bygone farmhouse dating back to the early 1800’s, and the amazing home of J. Morgan Puett, Mark Dion (Season 4), and their son Grey Rabbit.

As I parked, the car was approached by a woman in suspenders–the first of many pairs in this large-scale “living history” collaboration. Whereas the Skowhegan’s residency in rural Maine receives 1,643 applicants to be whittled down to 65 students for a nine-week summer residency, Mildred’s Lane is highly selective, accepting only 5 to 8 fellows a session, each of which must be recommended by the advisory board over two intensive three-week sessions. The young artists must gravitate towards a like-minded community, as the work-live-research environment experiments in combining all aspects of artistic life: researching, making, cooking, eating… We are so used to stories of the mythical solitary artist toiling away in the studio, that it’s a fascinating experiment to arrange the fellows into a focused, short-term collective, then release them back to different corners of the country. At times during the weekend, Mildred’s Lane was referred to as a museum, but in talking to Morgan she clarified that it is a “form of a new contemporary art complex(ity).”

At five o’clock, two of the fellows served as docents and escorted us around the treasure trove of buildings. The first was the farmhouse where Mildred Steffens lived with her common-law husband, Vincent Miller, for 86 years. It has been preserved since Puett and Dion moved in twelve years ago. The question with many historic sites and period-rooms remains how to faithfully narrate the story, the history of the space, but still utilize it as a living laboratory.

Dion, along with a recent fellows session, did extensive research on the life of Mr. Miller, finding he had spent the vast majority of time in the musty basement with his tools. They artfully rearranged Miller’s belongings, substituting in several contemporary materials, presenting the sense that he had stepped outside and never returned.

Photo courtesy of Rebecca Fuller.

One of the most powerful moments of the outing was the description of the graveyard. For Morgan and Mark, this wonderful endeavor as a long-term experiment is, of course, transformative for the fellows, but imagine the transformation Mildred’s Lane has brought to their lives. The sheer amount of friends and colleagues that assemble at their home each weekend is staggering. The shared experience of collaboration, of learning, and love is more than a bit overwhelming. Morgan has stated that when the day comes that she will be laid to rest on the property. Pennsylvania state law mandates that no one can be buried where there is not a pre-existing cemetery, so Mark built one. It contains headstones for their heroes, their inspirations. Benjamin Smith Barton, the botanist and physician, lies there. The spirit of painter and naturalist, Charles Willson Peale, resides along with the monuments. Peale founded the first natural history museum, Philadelphia Museum, which was one of the first to adopt taxonomy, and was wildly popular for displaying mastodon bones—an obvious influence on Dion’s work and life.

Photo courtesy of Rebecca Fuller.

At six o’clock, with the aroma of corn cooked over the fire, about 55 visitors, fellows, and visiting artists gathered on the lawn for dinner. The night’s guest-chefs were Liz Chaney, Rebecca Henderson, and Berangér LeFranc, all recent sculpture students of Hope Ginsberg’s from Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA. Their challenge was to create a cohesive comfort meal using recipes, or family heirlooms, passed down from generation-to-generation. In many ways the supper was a work of art itself. The plates were laid out below the tablecloth, leaving the cuisine sitting directly on top. The ancestral mac’n’cheese, kale stuffed with curried lentils, sweet corn-on-the-cob, and squash soup were truly spectacular.

Photo courtesy of Rebecca Fuller.

Shortly after seven in the evening, we reconvened in the magnificently refurbished open-air barn for a back and forth ‘slide/slam’ between Mark Dion and Robert Williams, an artist and academic from the Cumbria Institute of the Arts, plucked directly from the National Arts Club. The pair explained that mutual admiration was instantaneous, when introduced to discuss their first collaboration for the first Artranspennine exhibition. The conversation lasted for hours and, rather than touching the project at hand, focused on vintage b-horror movies, cowboys and dinosaurs.

Over the past eleven years their friendship has resulted in six extensive projects. The largest of which, The Tasting Garden at Lancaster (1998), was the main focus of the night’s lecture. Robert with his laptop and digital projector, and Mark with a Kodak slide projector (“an analog man in an increasingly digital world”) [my note: the slide projector had a much clearer, sharper picture], they gave a history of a victory garden completely devastated by an invasive species. They examined the repercussions of what happens when a particular species of fruit does not produce sales at the market. The grocer no longer makes money off the product, so orders to farmers are halted. The farmer begins to no longer grow these fruits, eventually seeds disappear and we are left with Golden Delicious, Granny Smiths, Red Delicious, and so on… but, in the super market we never consider the extinction of non-commercial fruits. (Gravestones were created for the fallen fruits, such as the Ambrosia Pear. The gravestones were in the Park, in the garden – essentially beside the paths – on the way to the main fruit sculptures. Where as the big sculptures are atop a concrete plinth – these gravestones for the fallen fruit are in the grass – easy to miss.)

For the exhibition they envisioned and realized, a walking garden where the public could stroll through pathways picking cherries, pears, peaches, plums, and apples on the brink of disappearance. They planted 22 fruit trees, with a corresponding bronze sculpture as signage with a fully ripened version at the top of a concrete plinth. Sadly, as the economy declines, areas that thieves previously respected as off-limits are now seen as open game. As the walled-in garden was closed for renovations, burglars slipped in and proceeded to remove 21 of the 22 bronze sculptures. An estimated 10,000 English pounds ($16,394) worth of bronze were scrapped and sold for a measly few hundred pounds. (In another case down in Hertfordshire, a Henry Moore sculpture valued at $4.6 million was stolen, scrapped and the 2.1 tons were melted down for a total score of $4,137.00.) Despite the somber subject, they moved on to discuss the great Tate Thames Dig. It was a complete pleasure to watch them stroll down memory lane. The two old friends puffed cigars – smoke billowing in the light of the projector.

Being the last night of the current fellows session, throughout the day there had been speculation mounting around the creation of a bonfire by visiting-artist Simon Morris. Around nine o’clock, we got our answers. In the darkness we watched as several assistants doused a massive mound of wood with a can of oil. When all was properly situated the artists’ teenage son appeared, complete with bow and an arrow piercing a stack of flaming marshmallows. The Prince of Thieves it wasn’t, but soon we were bathed in the festive light of the blaze. It was soon back to the barn for an all-night dance party.

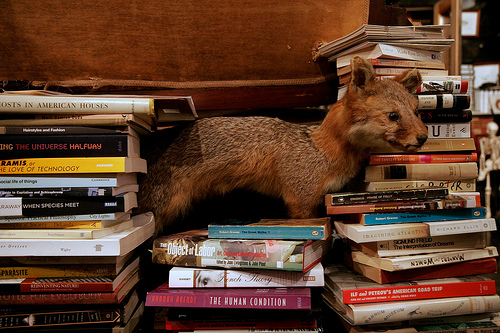

Cut to three in the morning and time to crash. I was offered up the most wonderful room I’ll ever stay in. The thousands of books with taxidermied animals with eyes on me from all angles, the cases of stuffed birds, snakes and frogs preserved inside mason jars, anatomical models, botanical illustrations… It was like being locked overnight in Deyrolle, the Paris natural history emporium, or more accurately like living in one of Dion’s Wunderkabinetts.

It is difficult to know how best to accurately summarize a night I thought was so special.

Please visit the website, www.mildredslane.com.

Little creatures poking out from everywhere! Photo courtesy of Rebecca Fuller.