“On the Moon and Beyond” June 10-September 14 2009, Courtesy of the Streaming Museum. “Natural History of the Enigma” transgenic artwork by Eduardo Kac. Selections from video oratorio, “Paradiso” by avant pop composer, Jacob Ter Veldhuis, video artist Jaap Drupsteen.

Forty years ago Americans watched in awe as a spectacle of scientific achievement unfolded on their television screens. From the comfort to their 1960s living room sofas they watched as astronauts bounced over the surface of the moon and issued eloquent exclamations at the human capacity to transcend the physical and imaginative horizons that bound our recent ancestors. While the Apollo 11 mission is now remembered much more for its political value in demonstrating American technological dominance over the Soviet Union than for any great contribution to scientific knowledge, the fortieth anniversary of the moon landing has renewed flagging enthusiasm for scientific endeavors whose main purpose is to set new frontiers for the pursuit of scientific glory.

In projects like the proposed colony on Mars, in which a great boondoggle is reincarnated as an end in itself, science seems to verge on becoming art. The transfiguration is rendered complete in the video exhibition “On the Moon and Beyond” that is on view until September 14th at the Streaming Museum, Streaming Museum the web-based gallery of the Chelsea Art Museum’s Project Room. What intrigues me about this exhibition is how it retrospectively renarrates the moonwalk of 1969 as a performance artwork, and thus implicitly asks whether it wasn’t always, on some level, a kind of moon dance.

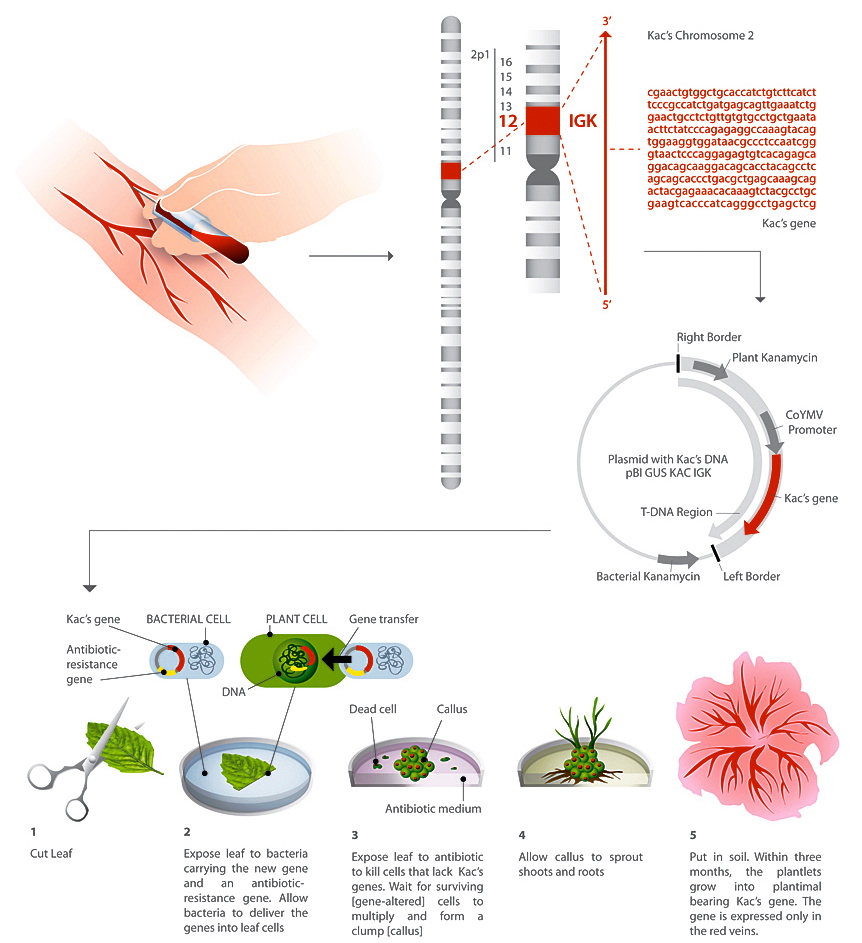

“On the Moon and Beyond” mixes selections from Dutch composer Jacob Ter Veldhuis and video artist Jaap Drupsteen‘s video oratorio, “Paradiso”, a composition based on Dante’s Divine Comedy, with images and text from Eduardo Kac transgenic artwork “Natural History of the Enigma” (2009), which was on view at the Weisman Art Museum in Minnesota from April 17th to June 21st. Kac is well known for his work with genetic engineering, most famously, for “GPF Bunny” (2000), an albino rabbit that was genetically modified to express a jellyfish protein that glows fluorescent green under black light. The work provoked heated debate about how far we should go, as artists or scientists, in altering natural phenomena for our own purposes. As an artwork, Alba the fluorescent bunny functioned as a magnet for widespread anxieties about the development of transgenic mice, rats, bacteria and other organisms used in biomedical research and agriculture.

Kac’s new work, a transgenic petunia that expresses a DNA sequence derived from the artist’s own blood aptly named “Edunia,” is technologically impressive, but visually understated by comparison. The audacity of Kac’s transgression of species – and indeed higher taxonomic boundaries – is rendered palpable, however, by its framing between film footage of Niel Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin shifting the global balance of power and uttering the words that would later prompt one critic to call Alba a “great hop for mankind.” Art and science find shared purpose here in pursuit of the narcissistic sublimity of gazing upon the enormity of our own achievement.

Eduardo Kac, "Natural History of the Enigma," transgenic flower with artist's own DNA expressed in the red veins, 2003/2008. Courtesy of the Weisman Art Museum. Photo: Rik Sferra

We won’t have another opportunity to view the Edunia ‘in the petal’ because all of the plants, along with the live seed packets that formed part of the Weisman exhibition, were to be destroyed as an environmental hazard on the orders of the National Institute of Health. Just as Kac was accused of faking the surviving images of Alba, there have been sustained efforts to prove that the moon landing was a cinematic fabrication. As the music reaches a crescendo in “Paradiso” and astronauts are resignified as angels, “On the Moon and Beyond” prompts the question, what does it mean to ‘believe in’ science? – literally, to believe that astronauts landed on the moon, or that Kac actually engineered his organisms, and, figuratively, to place our hopes, our trust, and our faith in expanding the horizons of our mastery of inner- and outer-space?

Eduardo Kac, "The Making of The Natural History of an Enigma", 2008, Courtesy of the Artist

Pingback: New guest blogger: Max Weintraub | Art21 Blog

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog