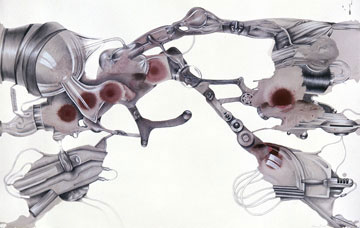

Vesna Jovanovic, "New Mitosis," 2008. Ink spills, graphite, pencil. Courtesy the Artist.

In an exhibition currently on view at the International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago, artist Vesna Jovanovic both courts and antagonizes the intersection of art and science in the role of the medical illustrator. In this traditional division of labor, science provides the content and the standards of representation, while art serves as the means of communication. Where other artists have inverted this relationship by employing scientists and scientific techniques as means for producing novel artifacts [such Eduardo Kac’s transgenic organisms or Gary Schneider’s Genetic Self-Portait (1998)], Jovanovic works within scientific conventions of realism to explore how they have been internalized and how they might be transformed by artistic practice.

This year’s exhibition of Anatomy in the Gallery, on view until October 16, juxtaposes work by students and faculty from the University of Illinois – Chicago’s Biomedical Visualization program with Jovanovic’s series of drawings based on ink spills, Pareidolia. ‘Pareidolia’ is a psychological term for the common tendency to perceive order or significance in random visual or auditory stimuli, like seeing the shapes of animals in clouds, or faces in the moon. Jovanovic uses ink spills, like rorschach tests, for exploring the ways in which scientific imagery and concepts reside in our collective unconscious—where, it seems, medical instruments, chemistry equipment, organs, and blood vessels grow and mutate into monstrous chimeras.

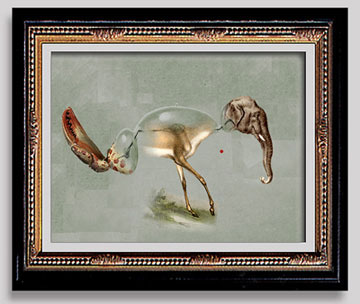

Eva Sutton, still from "Hybrids," 2000. Installation on LCD flat-panel.

I had the opportunity to see selections from Pareidolia, along with pieces from Jovanovic’s Hybrid series, in another scientific venue, the Gordon Center for Integrative Science at the University of Chicago last May. In Timekeeper (Self Portrait) (2007), inkblots are replaced by medical images that reflect a lifetime of the artist’s ailments and injuries. In the shadowy images produced by x-rays and MRI scans, Jovanovic discerns, through a process that could also be likened to pareidolia, a kind of physiological unconscious. The result is an anachronistic cyborg composed of new and old machines, human and animal parts, a body that is at once imaginary and hyper-real.

As I looked at Jovanovic’s hybridized versions of herself, I was struck by the contrast with other artists’ works I’d encountered previously, in which the idea of hybridization was associated with irreversible deviation from familiar standards of personal or species identity. This tendency is prominent, for example, in Eva Sutton‘s Hybrids (2000) a faux-type specimen painting that suggests an Audubon illustration – or a genetic engineering experiment – gone terribly awry. Sutton’s scientific realism is a carefully orchestrated aesthetic illusion. The image is actually displayed on a computer monitor (complete with an ornate gold frame), which the viewer can manipulate to combine parts of the animals in ways that could never take place in a nature that “takes the shortest path” and “makes no leaps.” With the click of a mouse, Sutton indulges the viewer’s “eternally irrepressible drive to intervene in nature, which is a fundamental characteristic of being human.”

Vesna Jovanovic, "Timekeeper (Self Portrait)," 2007. Medical scans, ink, graphite. Courtesy the Artist.

Is it the possible expression of this irrepressible drive that arouses horror at the intersection of art and science? Is this what must be held in check by the division of labor between the scientist and the illustrator? If Sutton’s work tantalizes and cautions us about a fantastical future, Jovanovic’s comparably restrained hybrids locate those fearsome possibilities closer to home, as we come to see in the most accurate scientific images strange chimeras of ourselves.