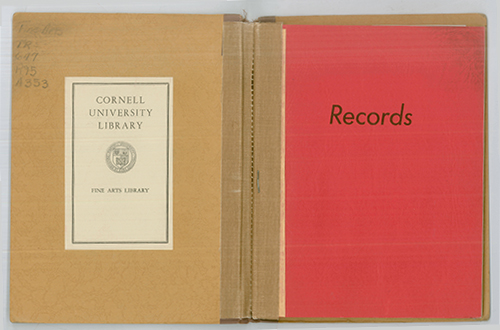

Ed Ruscha, "Records," 1971.

In the 1960s and 70s, American artist Ed Ruscha conceived, designed, and distributed a series of books. Their titles, such as Thirtyfour Parking Lots (1967), Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965), and Various Small Fires (and Milk) (1964), described the books’ contents with deadpan accuracy. Despite their relatively small editions, ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand copies, Ruscha considered the books to be mass-produced commodities and sold them at a low price through commercial outlets (1). As books, Ruscha hoped they could have a presence in culture beyond the limits of the art world. “The way they’re supposed to be seen,” he said in 1981, “is when someone hands someone else just one book at a time and place where they don’t expect it.”

To this end, Ruscha’s works borrowed from common book design and utilitarian photography instead of traditional art practices. Still, despite their familiar appearance, Ruscha’s books represented an ambiguous new genre situated between narrative and index. This unstable ontology is emphasized through the titles’ puns and non-sequiturs as well as the books’ multiple modes of information, which include linguistic, photographic, and indexical signs (2, 3, 4). In this way, Ruscha transformed books into artworks and information into poetry.

Of course, we now recognize Ed Ruscha’s books as historically significant artworks that mix pop, surrealist, and proto-conceptual sensibilities. Ruscha himself has characterized them as his most “Duchampian” work. However, because of this recognition, it is now difficult to experience the books in the way Ruscha originally intended. Not only have the works become overly familiar, but the books’ rarity have made them the exclusive property of institutions. For this reason, Ruscha’s books are now mostly seen through the glass of museum vitrines, where they are more artifacts than artworks.

The books’ loss of their original function is not only due to an inevitable art historical process. It is also an outcome of the work’s failure as a mass produced commodity and its failure, finally, to transcend reification. It may be instructive in this case to briefly compare the books to their inspiration: Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades.

In contrast to Duchamp’s recreations of his famous Readymades, Ruscha has neglected to re-release his books (5, 6). The books’ obsolescence reveals their status as mass-produced commodity to be historically contingent, as if the books had an expiration date that has long since passed. Not even Ed Ruscha, it seems, can keep up with global capital. It is also interesting to note that the dissemination of information on Ruscha’s books has deadened, rather than enlivened, their affect. When grouped together and schematized, as I have done here, Ruscha’s particular brand of surrealism seems methodical rather than mystical (7). By comparison, the Readymades seem to better resist categorization due to their comparative variety and Duchamp’s own inconsistent recounting of their histories and meanings.

All this is to say that Ruscha’s books now exist in a kind of artistic afterlife, still tied to their previous functions and meanings but seemingly retaining less and less of them. We know what they meant, but the question of what they will mean has been left open. That was then, this is now.

Notes

1. When coming across the books now one can often find light pencil drawn numbers on the inside cover, indicating their original price was only a couple of bucks.

2. Records (1971) resembled a scaled down log book but contained black and white photographs of LPs and their respective album art.

3. I am thinking here of philosopher C.S. Pierce’s famous typology of signs: icon, index, and symbol. See also Rosalind Krauss’ “Notes on the Index.”

4. The most obvious example of Ruscha’s use of indexical signs can be found in Thirtyfour Parking Lots. In this collection of aerial photographs of Los Angeles parking lots, the different intensities of oil stains denote the best parking spots.

5. The re-release is practically a given for any recent mass market cultural object. A familiar example of this might be the recently released re-mastered versions of The Beatles’ catalog.

6. For a discussion of Duchamp’s recreated Readymades see Helen Molesworth’s Part Object Part Sculpture.

7. Ruscha is obviously aware of this process when he says, again in 1981, “…the sheer number of things waters it down, weakens it. When it’s an established thing, and everyone understands it, it’s lost its original function. If everyone knew what the books were about, the whole thing would be totally different. That’s why I was interested in the book form. Duchamp had already killed the idea of the object on display. After what he did, it would be hard to surprise anyone. So books, conventional books, were a way for me to catch my audience off-guard.”