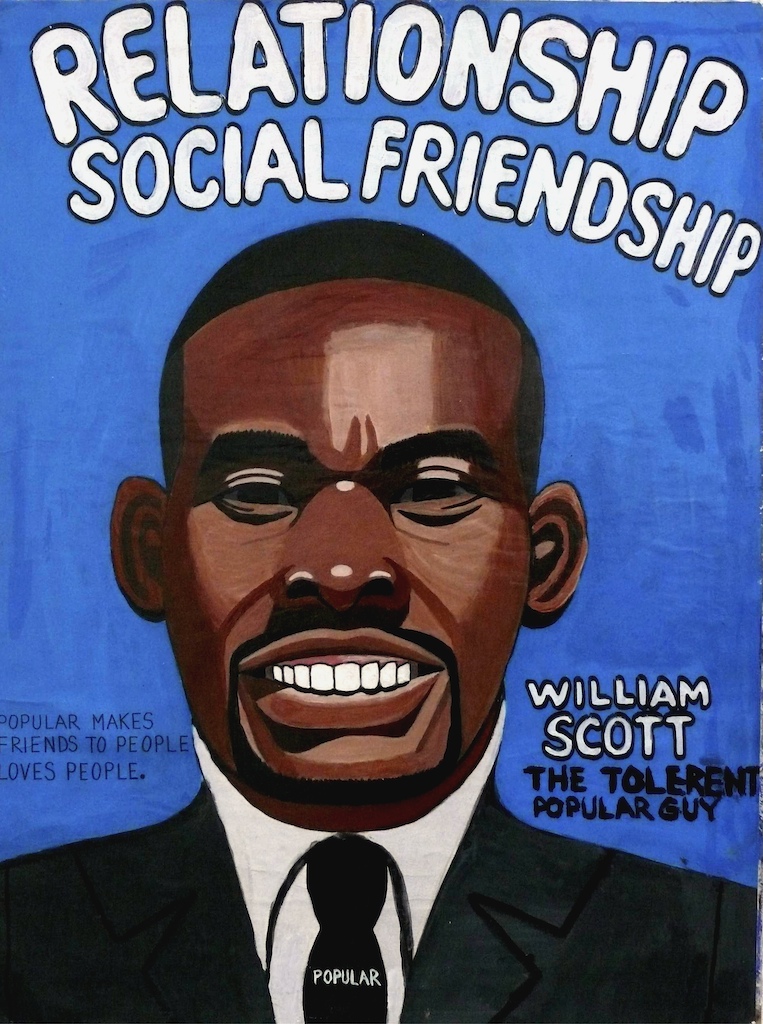

William Scott self-portrait (courtesy of Creative Growth)

How many artists are there in the world right now? Let’s be honest. No matter how globalized we’re constantly being reminded the art world is – in symposia, biennales, lists of powerful people, and the perennial curatorial job description as”‘working between Berlin, LA and Sao Paolo” (pithily pointed out in Hyperallergic) – the contemporary art world barely represents a fraction of artists actually working right now. The art world is a world, not the world, and so it’s perhaps ironic that the institution currently most actively and successfully articulating that idea has sprung up alongside the festivities and venalities of the Frieze Art Fair: the Museum of Everything, a temporary exhibition space in north London, established to display “outsider art” (according to the Museum, “the untrained, unintentional and unseen”).

There are many miraculous things about the Museum of Everything, one of which is its location, right in the heart of the very posh and celebrified Primrose Hill. A huge, semi-dilapidated space that’s been both a dairy and a recording studio, it’s a series of small, scruffy rooms and one huge one, in cracked concrete and rusted beams, which is much less of a cynical presentation style for outsider art than it sounds. The perennial problem of outsider art – apart from its roll call of artists, which includes Henry Darger, Bill Traylor, and Martin Ramirez but not, say, Henri Rousseau or Vincent Van Gogh, despite their very evident fulfillment of “outsider” criteria – is that of presentation. Is a clean, white, sterile gallery space appropriate? Probably not, given its similarity to a mental institution. But a studiedly “mad” and shambolic location is pretty patronizing, too. The Museum of Everything has hedged its bets, and it’s probably as good as it can be — eccentric to a point, but careful and thoughtful above all. The collection, amassed by filmmaker James Brett, has no precedent in UK museums; there’s no outsider art in the Tate Modern collection (or at least none displayed), and the nearest dedicated museum space is in the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin. The absence is puzzling, given the rich tradition of eccentricity in the work of William Blake, say, or the amazing Richard Dadd. Jeremy Deller and Alan Kane’s Folk Archive, shown in the Barbican several years ago, came close, but there’s still no UK equivalent to the American Folk Art Museum in New York. Brett’s museum points towards the articulation of voices left out from mainstream British museum collections, although its permanence is somewhat in question (“if people come, we’ll stay open”).

It’s a collection of amazing quality. Despite no Ramirez, Wolfli or Hundertwasser, there’s a suite of staggering Henry Darger drawings and Bill Traylor paintings as good as any in US collections. Darger’s work continually eludes reductive analysis. His 15,000 page illustrated novel, The Story of the Vivian Girls, prefigures so many contemporary artists’ work, from Jeff Koons to Peter Doig to Marcel Dzama, that it’s sometimes difficult to imagine him working entirely guilelessly. Yet Darger did, working on his vast manuscript and several others entirely in private; this is, as Peter Schjeldahl pointed out, “a culture of one.” And those seeking psychoanalytical rebuses in Darger’s skipping, panicky prepubescent girls would do well to address the works themselves, which are stranger and more resistant to join-the-dots analysis than the biography might suggest.

Brett’s collection also features significant works by artists fostered through Creative Growth in Oakland, California. In a talk by Creative Growth director Tom di Maria and White Columns director Matthew Higgs during Frieze, the work of this nurturing organization – and its roots in radical politics – was discussed. Established over 35 years ago to provide studio and exhibition space, as well as tuition and support for local artists with disabilities, Creative Growth is (in Higgs’ words) “the most important cultural institution of our time.” Higgs has shown a number of Creative Growth artists at White Columns in New York, including the bound objects of Judith Scott. Scott’s works – bulbous, hanging forms, like internal organs or musical instruments, tightly bound in coloured threads – seem unwilling to be described as sculpture. Although artistic kinship can be found in the work of Franz West or Louise Bourgeois, the fact that Scott, who died in 2005, was a deaf woman with Down’s Syndrome who came to art making late in life via Creative Growth, transforms the viewer’s experience. So complete and insistent is Scott’s work that it renders artistic parallels somewhat futile, and comparable artists mannered.

That earnest intensity makes many outsider works both compelling and disturbing. Given that this is work made in “a culture of one,” what’s the role of the viewer here? One can feel complicit in a kind of voyeuristic, sometimes prurient fascination with the lives of the unwittingly and unintentionally excluded. It’s easy to find oneself convulsed in art world guilt over these works, but it’s disingenuous to self-flagellate over the sensation of reading the diaries of madmen. If the works’ communication is only with themselves (which is perhaps the abiding connection between artists whose work is as hugely diverse as the many thousands of nuanced “conditions” they labored under), then the viewer is experiencing a kind of pure blast of creativity unfettered by the heavy breathing of institutional requirements or conventions.

Art is made everywhere, all the time. Another Creative Growth artist, William Scott (no relation to either Judith or the British abstract painter), is shown in the Museum of Everything in some depth. His paintings act as a kind of surrogate social life denied to the artist himself. He appears as “The Tolerant Popular Guy” in a number of self-portraits, and shows himself as a high school basketball star, a besuited prom attendee, a successful police officer, a happy husband. His meticulous pencil drawings show maps of towns he’d inhabit in a “normal” life; he makes paintings of a utopian future San Francisco, ruled over by beaming, voluptuous female bureaucrats. Scott’s disabilities mean that he has had to fictionalize a conventionally successful life; the basketball portrait is emblazoned with the phrase, “Reinvent The Past.” Given that so many of the artists we’d conventionally classify as “outsiders” so successfully, and so variously, fulfill the criteria we should be demanding from artists of our time – command of materials, breadth of imagination, frank and unflinching assessment of the world around them – is it time to start thinking outside-in – and inside-out?