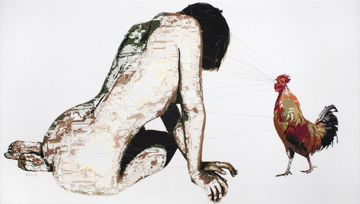

Alicia Ross, "Motherboard_6 (A Chicken Waits for a Good Cock)," 2008. Cross-stitch on cotton, 72 x 41. Courtesy the Artist.

This young artist’s Motherboard series features appropriated Internet porn—nubile women sprawl across large cotton panels, cross-stitched in silver and gold thread with digital precision…Witty videos filter sex scenes through those round eye-test patterns of colored dots you might remember from grade school. Substantially more men than women are color-blind—Ross offers one way to subvert the “male gaze” amid the Internet’s panopticon of voyeurism. — Village Voice

In pursuit of finding more groundbreaking contemporary work that explores the self (and the shame of being the self), I had thought of Alicia Ross. I remember the first day I met her, when I was doing a photography project at a company she then worked for in Cleveland. She is bubbly, kind, outgoing, and (I mean this as a true compliment, Alicia) vulnerable. In other words, she is so Midwestern that I long for her kind of smile as I now wander the streets of ice cold NYC. When she handed me the catalog to her recent exhibition at the Black and White Gallery in Chelsea, I was blown away. Her work is truly provocative, sublime, rich with color, texture, and questions. I wanted to have four of those questions answered, and like a good Midwestern girl, one that likes to cross-stich and embroider pornographic images at that, Alicia responded.

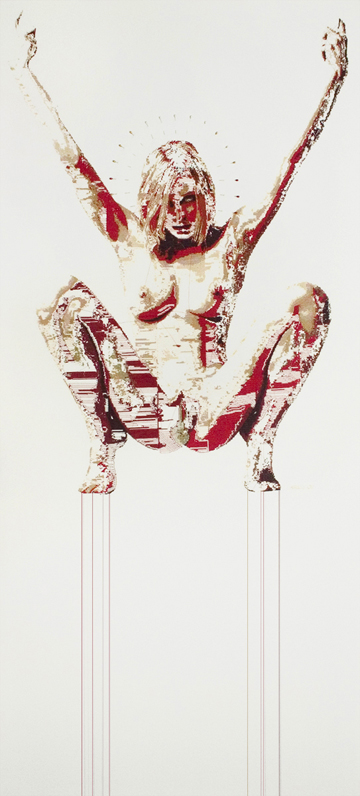

Alicia Ross, "Motherboard_5 (The Siren)" (detail), 2008. Cross-stitch on cotton, 36 x 51 in. Courtesy the Artist.

Maria Stenina: Your work is so sinful. It is not a woman’s place, after all, to explore pornography and overt sexuality with such craft and beauty. Can you address your dealings with the grotesque and the sensual?

Alicia Ross: My work isn’t necessarily an exploration of the grotesque or the sensual independently, but rather an examination of the marriage between the two. The tension that I am specifically interested in is the domestic woman vs. the woman of sexual desire or the conflict between mother vs. mistress. The work isn’t necessarily taking sides between the taboo or the ladylike but materializing the balance for the viewer to decipher.

I think it’s interesting you would use the word ‘sinful.’ Unless you see sexuality as sinful, I don’t think the work is sinful at all, but honest. I do think it’s precisely a female gesture to take something taboo or grotesque and want to make it beautiful. Just like the work is taking pornographic images and through manipulation and sometimes by sheer output, is transforming the images into a more widely excepted form: embroidery. To me, the whole point of the work is to question two often clashing, feminine impulses.

(Interviewer’s note: I should have said “deliciously sinful,” as I meant it to be a positive kind of sinful.)

Alicia Ross, "Motherboard_5 (The Siren)," 2008. Cross-stitch on cotton, 36 x 51 in. Courtesy the Artist.

MS: Your work, it seems to me, comes from a private, taboo place where issues of female sexuality are explored in vivid detail and then thrust out onto the viewer in a way that is startling and impressive. What do you hope the viewer’s experience is?

AR: I’m more interested in exemplifying the conflict rather than choosing sides. In my series of Samplers and Motherboards, I tried to blur the line between female figures, by removing them from their context and allowing the viewer to distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable or private and public. By making the images startling or impressive I feel the intended question becomes more obvious to the viewer.

MS: Where do you plot your work on the map of contemporary art-making? What is its significance in the landscape of societal environment?

AR: The tension between mother vs. mistress has been around for decades. But as the stereotypical roles of the sexes become more ambiguous, this conflict becomes more outstanding. Women are not always given the opportunity to explore both their domestic side as well as their sexuality—but rather forced to choose between them. This impractical choice creates the environment for this tension to emerge. This historic conflict is being exemplified throughout pop-culture, from Desperate Housewives and Madmen, to the media’s response to reality shows like Jon and Kate Plus Eight or the Casey Anthony trial.

MS: What is your relationship to your work? The craft is time-consuming and the subjects are seductive. They are exploited. They are powerful. Do you love them or hate them?

AR: I don’t love or hate the individual pieces themselves, though my emotion towards the pieces’ subject matter is strongest during the design phase. Much like the content of the work, my roles of artist and seamstress are rather disjointed. The most laborious part for me is the design part—searching the Internet for the right images to appropriate, digitally manipulating the images, choosing thread colors, digitizing the pixels to stitch, etc. Most of the logistical questions are answered before I start sewing. The sewing stage is very time-consuming, but that is really more of an output phase for me. It’s during this time where I can really tap into my own domestic compulsions.

Alicia Ross, "Motherboard_7 (Sacred_Profane)," 2008. Cross-stitch on cotton & pearled needles, 40 x 90 in. Courtesy the Artist.

Please visit Alicia Ross’s site for more images from Motherboard and newer projects.

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog