Stephen Kanner, Malibu 5 House, Malibu, CA, 2008

Sustainable architecture is in danger. This might sound like a surprising claim, given the fact that never before has “green” living been such a popular concept, nor has “eco-consciousness” been so en vogue. Yet the trendiness of green living is exactly what imperils it; as a trend, sustainability runs the risk of lapsing out of style, a fad that can go out of fashion as easily as it came in (if Brad Pitt’s interest in green architecture wanes, will ours?).

One of the greatest difficulties of discussing sustainable architecture is that there is no single definition of the idea to start with. Some groups characterize it as design which foregrounds energy efficiency as a concern, using passive solar design or alternative energy sources; some describe it as architecture that uses alternative materials, frequently local, recycled, or reclaimed; still others consider it to be building that highlights a general attitude of environmental consciousness. Obviously, such guidelines are fuzzy at best. My worry is that, given this laxity in defining sustainable design, we must resort to parameters most famously defined by Justice Potter Stewart in reference to pornography: when it comes to sustainable building, we might think we know it when we see it.

Take Stephen Kanner’s Malibu 5 house, for example. This 3,500-square-foot house, located in a posh Malibu neighborhood, faces the Pacific Ocean and features a number of sustainable elements—recycled materials; reduced energy consumption; passive heating and lighting using the sun as the primary source; and air conditioning from the California breeze. The roof is fitted with photovoltaic and solar panels to provide hot water and off-the-grid power. The structure’s two main volumes, both C-shaped in plan, are separated by a courtyard, and the interior spaces open on at least two sides to facilitate cross-ventilation. The home is wrapped in low-emittance, argon-filled windows to curtail heat loss and gain and to flood interiors with natural light.

So, sustainable indeed. But as much as Malibu 5 adheres to a commendable green program, it is also concerned—like much elite sustainable architecture under construction today—with announcing its sustainability through its appearance. It lets us know, with its minimalist forms, with its unornamented surfaces, with its geometric, modernist composition, that its inhabitants are as fashionable as the architecture they selected for their home (and I still can’t help but wonder what anyone does with 3,500 square feet of living space).

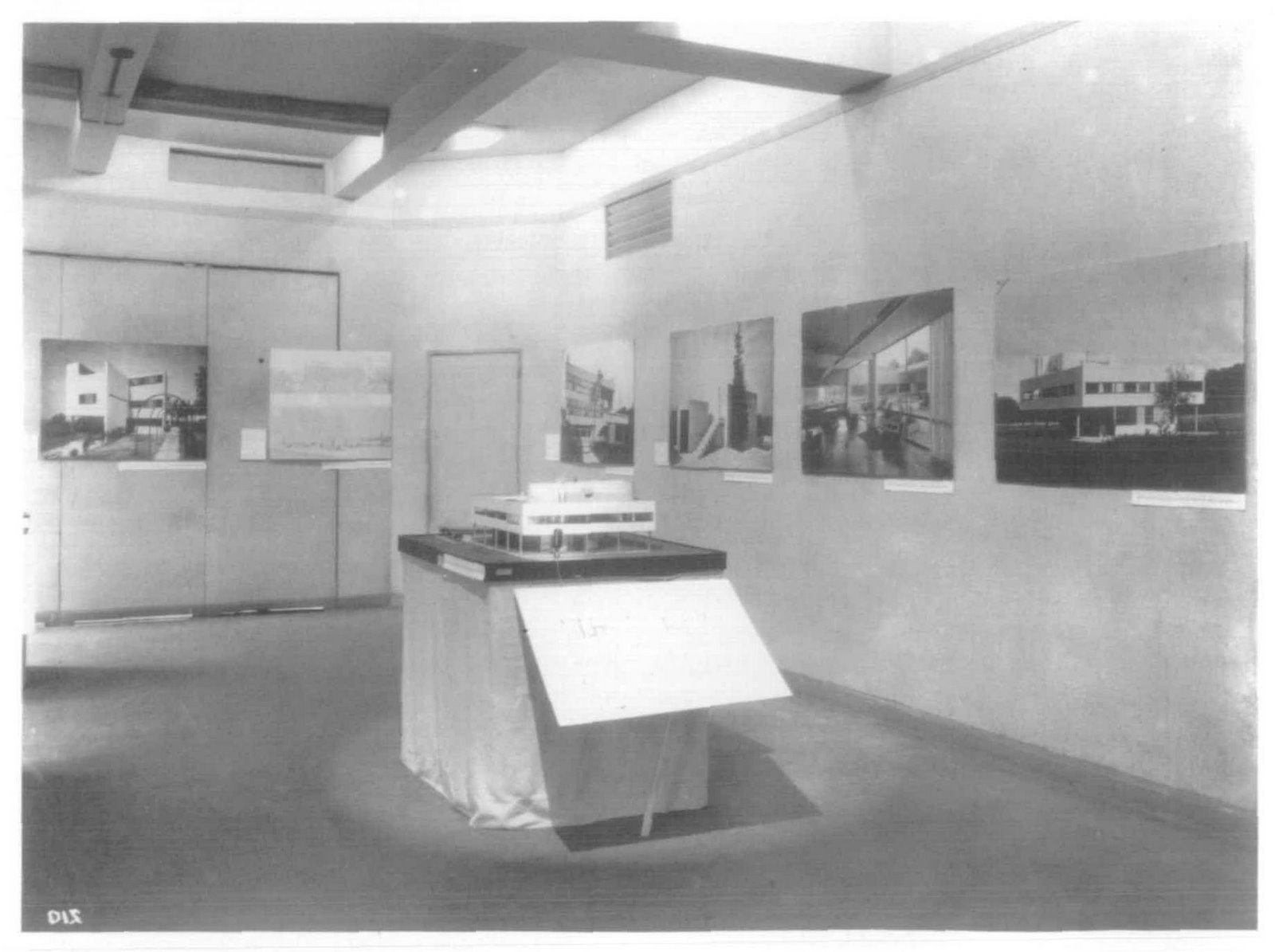

Philip Johnson (curator), International Exhibition of Modern Architecture, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1932

The difficulties resulting from privileging fashion over method—or style over substance—are well illustrated by history. Remember the colossal impact of Philip Johnson’s and Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s 1932 MoMA exhibition on what they termed the “International Style”? The buildings selected for the display had been carefully chosen to demonstrate three formal principles in their most codified manner: volume over mass, regularity over symmetry, and a rejection of applied ornament. Nothing was chosen that fell outside what Johnson described as the “strict discipline” of the new style, shifting the terms of the modernist project decisively towards form. As early as 1932, the future of modernism was embattled, as soon as it became a style rather than a method; if architecture should be anything, it should be a problem to be solved, not a modish outfit in which to clothe our buildings. There’s something to be learned from the impact of assigning an architectural style to an age, which is that no single architectural style can meet the needs of an unruly culture.

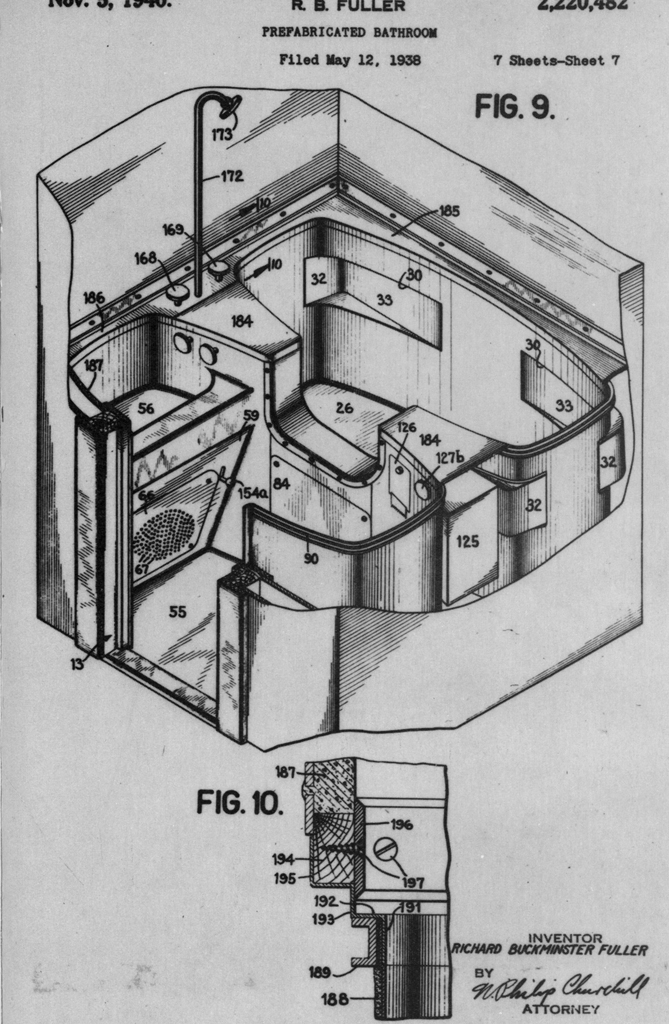

Buckminster Fuller, Dymaxion Bathroom, developed 1936

The year 2008 saw both the depths of the Great Recession and—not at all coincidentally—a resurgence of interest in the architecture of Buckminster (“Uncle Bucky”) Fuller. Fuller was an architect much preoccupied by efficiency, and very little interested in style; he was sustainable long before it was trendy, he wanted people to reduce their carbon footprint, and he didn’t think people should take up more room than they need (Malibu 5, I’m looking at you). His interest lay in creating prototypes that could be standardized, sold cheaply, and frequently assembled on one’s own without the help of architects or contractors. His Dymaxion Bathroom, developed in 1936, was a remarkable idea: rounded edges with no nooks, crannies, or grout cracks to make clean-up easier; equipped with “Fog Gun” showers that created a vapor comprising only a cup of water; and a waterless “packaging toilet” which shrink-wrapped waste to be used later for composting (Fuller pointed out that ordinary toilets use approximately 2000 gallons of pure drinking water per year to flush one human’s “exhaust” which, if dried out, would barely fill two five-gallon buckets). It is this kind of problem-solving that a new generation of architects is learning to appreciate.

Many of the changes that need to occur in order for real sustainable architecture to thrive must take place at the level of policy-making at the municipal, state, and federal levels. Standards should be established to designate new design or renovation as “sustainable,” and individuals or groups whose structures meet these standards should enjoy real economic rewards (for example, some cities and states offer tax relief for LEED-certified buildings). I don’t propose a purely capital-driven attitude towards sustainability, but rather one in which there is some consensus about what constitutes sustainability and some agreement that the way should be eased for those who choose to act towards the greater good. Formally, architects should keep sustainable architecture weird, idiosyncratic, and experimental—not for the sake of maintaining some mythic counter-cultural status, but in order that architectural idioms can be developed that will suit a multiplicity of individual tastes.

Julia Walker is Professor of Art History at the Savannah College of Art and Design.