"Antidiets of the Avant-Garde: From Futurist Cooking to Eat Art" cover art. University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Some 30 years after the Italian poet and founder of the Futurist movement Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote The Futurist Cookbook (1932) and proposed a revolution in food, the European avant-garde artist Daniel Spoerri, who is closely associated with the Fluxus art movement, opened Restaurant de la Galerie J in Paris, a fully functional business with waiters from the art world. Four years later, in 1967, he opened Restaurant Spoerri in Dusseldorf, featuring guest chefs such as artist Joseph Beuys; and in 1970, established his now famous Eat Art Gallery upstairs.

Two recent events have brought attention to these landmark moments in food-art history: the Futurist theme of the 18-day performance biennial Performa 09, which, among other events, kicked off with a gala dinner based on Marinetti’s writings; and Eating the Universe, the Kunsthalle Dusseldorf’s latest exhibition, which traces the character of Spoerri’s Eat Art projects from its origins through to today. It seems the perfect moment, then, for Cecilia Novero’s new book, Antidiets of the Avant-garde: From Futurist Cooking to Eat Art, due out in January.

Novero, a professor in the Department of Languages and Cultures at the University of Otago in New Zealand, has written extensively on the cultural history of food, German and European film, Dada, Viennese Actionism, and most recently contemporary “animal art.” Below, she gives a glimpse into her forthcoming book, in which she focuses on the connections between avant-garde studies and the culinary field in 20th- and 21st-century artistic production.

The following excerpts are taken from an interview conducted via email.

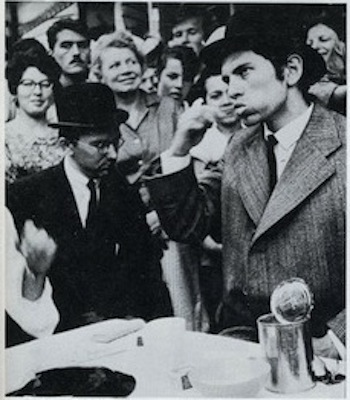

Marinetti eating pasta at Milan's Biffi restaurant, 1930. Courtesy Estorick Collection, via Cabinet Magazine.

Nicole J. Caruth: How do you define “antidiet”? Is it synonymous with the rejection of “taste” in art (i.e. anti-taste) or related to the French idea of dégoût/disgust?

Cecilia Novero: Antidiet is not always dégoût–that would work with Dada but not with Futurism. Antidiet is meant in the sense of anti-art, without being a synonym of it. If diet is a set of regulations that orders ways of eating, table manners, etc., the anti-diet counters these “bourgeois” and “Western” rules. For example, the ways in which we take pleasure, appreciate what is considered/constructed as the beautiful, and especially the ways we “taste” art and thus stop thinking about inherited concepts of beauty. In the avant-garde and neo-avant-garde, anti-diet also refers to acquired notions of “progress,” hence traditional historicist approaches to art and civilization.

NJC: What are some of the topics and sub-topics covered in your book?

CN: Antidiets deals with Futurist cooking, Dada poetry and manifestos, the culture critic Walter Benjamin’s writing on food, travel and art, and the European artist Daniel Spoerri and his Eat Art Project, which involved many others (mostly those artists known as Nouveaux Realists in France, but also others such as Robert Filliou, Dieter Roth, Andre Thomkins and, marginally, Piero Manzoni). The epilogue briefly traces the differences in aesthetics between this anti-art of food and more contemporary examples of food in/through art, including Janine Antoni, Ben Kinmont, Rikrit Tiravanija, and Jana Sterbak.

The first chapter, like the last, is devoted to the more direct employment of food in art, namely to the Manifesto of Futurist Cooking (1930), The Futurist Cookbook, and the Futurist restaurant, The Holy Palate (both 1931). In contrast, in Chapter Two on Dada (particularly the Dadaist artists in Zurich), and Three on Benjamin’s short texts on eating, the reader finds a rhetorical and performative use of incorporation [a term used by the author interchangeably with “devouring”]. One of the major suggestions of this study is that the antidiets, not just Spoerri’s, but also those of Futurism, Dada, and Benjamin, transformed some of the gastronomic principles of pleasure, taste, assimilation, and digestibility, as well as history, and mobilized those principles for a redefinition of art and the subject.

Daniel Spoerri, "Eaten partly by: Visitors of the Biennale of Sydney 1979," 1978-79. Dinner debris: knives, forks, plates, bread, bottle, glasses, glued to a screenprinted tablecloth mounted on wood, overall 100 x 220 cm. Gift of the artist, 1979 NGA 1979.2341.A-B © Daniel Spoerri. Licensed by Pro Litteris, Zurich & VISCOPY, Australia

- Rirkrit Tiravanija, “Untitled (the raw and the cooked),” 2002. Photo © Kioku Keizo, via www.operacity.jp

NJC: How do you distinguish the historical avant-garde from the neo-avant-garde? Is it with attention to particular dates or events?

CN: Let me start by saying that what initially interested me were the connections or, as I would like to call them, the “interferences” between two main fields that came to constitute the bulk of my book: avant-garde studies and the culinary. I call the interactions between the fields “interferences,” because the avant-garde texts studied here enact practices of estrangement and deconstruction of the culinary. I like to stress that my explorations do not underscore any continuity between the art and texts considered and gastronomic discourse; I don’t write a history of these connections. Rather, in general, my book suggests a number of constellated ideas that may offer less common perspectives on the European avant-garde. I inquire into antidiets and their “incorporation” to uncover a network of complex temporalities informing both the historical avant-garde and the neo-avant-garde…Through this analysis, in fact, the divisions and distinctions between the two are questioned.

NJC: What led you to write Antidiets?

CN: The initial impetus for Antidiets came from three short stories by Franz Kafka: A Report to An Academy (1917), A Hunger Artist (1922), and Investigations of a Dog (1931). My book, however, leaves these stories behind; they functioned rather as suggestion. In each, drinking, eating, and especially thinking about eating (even as abstaining from taking food), unfold as engines of writing, before moving on to engage more specifically the relations between art and knowledge and between producers and consumers of art.

In Investigations of a Dog, for example, the thinking process manifests itself as a constant noise, the rumbling of knowledge that music instigates, which then also accompanies it in the text. The text itself spins and whirls with no simple beginning or end, without any apparent direction. The dog’s nutritional, or essential questions remain unanswered and the “good food” is not found. Kafka’s story is not about food. It takes instead “thinking food” as the inescapable desiring energy that propels writing and artistic production. This textual, non-representational relation between “thinking food” and “writing” or, more broadly, artistic production, led me to identify a performative quality in food and eating as they manifest themselves in avant-garde manifestos, magazines, declarations, instructions, etc., as well as, surprisingly, in their actual cookbooks (e.g., The Futurist Cookbook). This is a crucial point I make, especially in the analyses of Swiss Dada. Performative here means an active rhetorical strategy that displaces food from its regular uses and turns it into words (names, insults etc.), thereby destabilizing both the usual practical grammars of food and the grammars of language.

Kafka’s A Report to An Academy raises the problem of costs of edibility: What is the boundary between the human and the animal, between he or she who eats and that which is eaten? The most important story by Kafka, however, was/is perhaps A Hunger Artist. Here, Kafka presents an artist whose very art—profession—is self-starvation. The artist’s art is to stage his own disappearance. In other words, the spectacle lies in this art’s and the artist’s self-erasure; its duration coincides with the process of vanishing of both art and artist from the public’s sight. This art thereby negates entertainment.

Ben Vautier. This image from Fluxshoe catalog shows the artist "eating mystery food from unmarked can" in a street performance, circa 1963. Via artcornwall.org

Not unlike A Hunger Artist, Fluxus artist Ben Vautier shut himself in a box and refused to eat for twenty-four hours. At the same time, this box was for all to see as a sign of absence, more specifically of art as absence (of the artist, of food, etc.). Note the role of writing here as well: a sign is over the box and states that Ben is in the box abstaining from food. Vautier staged this happening as the dialectical other of the Eat Art [projects] taking place in Daniel Spoerri’s gallery. Spoerri and his Eat Art—which was officially born when he started his restaurant in Dusseldorf in 1968 and opened the Eat Art Gallery in the same building in 1970—are at the center of the neo-avant-garde discussed in my book. A Hunger Artist demonstrates how important the dialectics between visibility and invisibility are in the neo-avant-garde of the sixties and seventies, in particular Eat Art’s insistence on food or eating performances, which offered to the viewer/consumer the opportunity to engage an art of time that in time would leave behind only a trace of itself.

NJC: You’ve written that the avant-garde eating was not pleasurable or beautiful, but rather represented the sublime as associated with fear. Have you found that the historical avant-garde disliked specific foods or ways of eating? If so, did that carry forth into the neo-avant-garde?

CN: The question of the antidiet, or counter-gastronomy in the avant-garde, is less about specific food, as it may be for some art today. [Rather], it is about the meaning and function of aesthetic systems, which in our modern tradition have been grounded in notions of “taste,” which in the realm of knowledge translates into the digestible.

In the first years of the twentieth century, avant-garde artists and critics from Picasso and Apollinaire through to the avant-garde of the sixties and seventies resort to the culinary to think about acts of production and consumption in the modern world. These actions (eating, cooking, and their metaphorical counterparts) bear more or less directly, and more or less politically, on the avant-garde’s immersion in and decomposition of this world that they ingest, bite into, and thereby construct anew in their works. The effect is a kind of active mimesis that varies depending on the artist. For example, in Dada, one encounters a parodic mockery of functionalized capitalist production and consumption, which introduces an element of dysfunction. Poverty and roughness, precisely the “rawness” smoothed out in the gastronomic discourse, render the avant-garde works/diets indigestible. In this context, the demand to eat well means to shatter the habits of the senses, of taste as much as of seeing, and to solicit attention to the world, an attention that goes beyond its representability to the eye. To incorporate the modern world is to ingest it and be absorbed in it, losing one’s own stable orientation or point of view, as well as sense of taste.

Taste demands a judgment that confirms the subject’s harmonious use of the faculties, thereby rooting the subject in a stable identity. But early twentieth-century onlookers of, for example, a Cubist painting are compelled to react physically, bodily, from the inside out, as it were. Georges Braque reacted to Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, saying, according to Fernande Olivier, “You paint as if you wanted to force us to eat rope and drink paraffin.” Viewers are compelled to learn to taste differently, to break out of the given and known experience of taste and of recognizable “flavors.” … These avant-garde works elicit disgust, a fear of disintegration, and loss of center that is not purely a negation of taste, but rather generative of a new diet, a sort of diet “after taste,” parallel to the idea of post-aesthetic art.

NJC: What’s your main objective with this book?

CN: My overall aim with the book it to rewrite the relations between the historical avant-garde and neo-avant-garde. Mostly, the latter has been dismissed as an inane and useless reproposition of the former acts of provocation … In contrast, my book argues that if one analyzes the recurrent trope and also material of food in both the avant-garde and neo-vant-garde, the temporal relations between these artistic movements are more complex.

Antidiets of the Avant-garde: From Futurist Cooking to Eat Art is available for pre-order through Amazon and University of Minnesota Press. The book is available both in hardcover and paperback. Eating the Universe is on view at Kunsthalle Dusseldorf through February 28, 2010.

Pingback: Forthcoming: ‘Antidiets of the Avant-garde’ by Cecilia Novero

Pingback: Lectures et colloques littéraires-2010 « A r t s & S c i e n c e s

Pingback: Summer reading | coldhearted scientist وداد