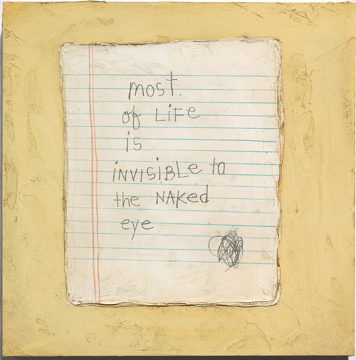

“Most of life is invisible to the naked eye,” proclaims Invisible, a painting in Squeak Carnwath’s new exhibition at Peter Mendenhall Gallery in Los Angeles. At first glance, it appears that the statement is scrawled in pencil onto notebook paper, but upon closer inspection, we see that Carnwath has formed the picture with only oil paint. As with all trompe l’oeil painting, upon discovering that we have been tricked by a pictorial sleight of hand, we find ourselves seduced into carefully examining its mechanics. In doing so, we may discover that–as with life itself–most of the happenings within Carnwath’s paintings are invisible to our naked eye. And–apologies readers– almost all of its happenings are invisible to the camera lens.

Squeak Carnwath, "New Research," 2009. Oil and alkyd on canvas over panel, 70" x 70". Courtesy Peter Mendenhall Gallery.

Ghostly marks hover beneath the filmy surface of each canvas, suspended at varying depths within countless luminous semi-transparent layers of paint. Observing the work becomes a process of active excavation, rather than passive looking. Even though more discernible words and images float to the glowing surface, they do not congeal into a single pictorial narrative, but force the viewer to assemble, bit by bit, his or her own meaning. Perhaps this demand for subjective interpretation accounts for why, according to curator Karen Tsujimoto, “the critical establishment has largely been occupied with the formalist and painterly aspects of [Carnwath’s] work, ignoring its iconographic features…”

Virginia Woolf, whom Carnwath identifies as a major influence, writes, in To the Lighthouse, “What is the meaning of life?…The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark…” During my days as an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, I studied with Squeak Carnwath. In the same way that Carnwath’s paintings offer up discrete images and statements that are simultaneously obtuse and resonant, her teaching style is characterized by the offering of koan-like anecdotes and assertions about the nature of painting, and the role of the artist in contemporary society.

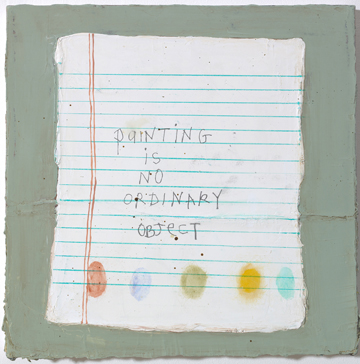

Squeak Carnwath, "Not Ordinary," 2009. Oil and alkyd on canvas, 10" x 10". Courtesy Peter Mendenhall Gallery

While Carnwath’s paintings may seem fragmented and almost entropic, threads emerge and weave together over time. Through the repetition of specific images, such as LP records, color grids, and handprints, a pictorial language develops. The forms, though rendered in detail, operate more as emblems or hieroglyphics than representations of objects. While Carnwath repeats the same images over many years, new symbols always emerge and eventually supplant the previous groupings of icons. Throughout her work, text–always painted or scratched into the surface with her distinctively urgent penmanship–occupies the same space as this image-based alphabet. Unified by misty membranes of glazes, the pictures and words seem almost interchangeable. Just as each of Carnwath’s images takes on the role of signifier, the scrawling letters do not simply reveal content, but also function within the realm of composition and form.

Carnwath presents casual grocery lists (“LETTUCE, MILK, FLOUR, BUTTER, EGGS, CARROTS”) alongside emotionally charged revelations (“Art, like science and philosophy, presents essential versions of reality”) and notes ostensibly derived from recent news stories (“There is new research which shows that maybe it was Gaugin who cut off Vincent’s ear…”). At the same time, her grocery lists could belong to any non-vegan, and the news stories quoted by the paintings typically come from international news media and public radio. The icons in Carnwath’s lexicon, though painted in a manner that is entirely unique, tend to be recognizable cultural symbols. Her newest paintings introduce several new signifiers, including large stamp-like contour renderings of American quarters and stylized Obama-esque figures. It seems that Carnwath’s paintings serve as an indexical registration of her private daily tasks, thoughts, and experiences, but also seek to channel the Zeitgeist.

Squeak Carnwath, "Alive" (detail), 2009. Oil and alkyd on canvas over panel, 65" x 75". Courtesy Peter Mendenhall Gallery

In “Alive,” a pair of Obama torsos smile at the viewer, with the words “yours and ours/ ours and yours/ everyone’s,” jotted underneath. Certainly this mantra refers to the ideal position of a leader –as belonging to his or her people. But I believe that Carnwath is also naming the common space that she hopes her work will occupy. In a 1993 interview with Richard Whittaker, Carnwath states:

I think of us [artists] as radio receivers. Our job is to be available, to accept information and to make it visible. And it works best when the information that we accept is the information we recognize as a part of our deeper self. We’re all individuals, but we’re also kind of the same. And it’s personal, but it can’t just be that…I think it has to be so that someone else can say, “That’s mine.” The viewer has to be able to claim ownership.

Squeak Carnwath’s paintings are on view at Peter Mendenhall Gallery, 6150 Wilshire Boulevard, Space 8, Los Angeles, CA 90048, until January 2010.

To hear more from Squeak, check out the Art21-esque video, “Imagination is the Mind’s Freedom,” produced by the Oakland Museum of California Art in conjunction with her 2009 survey exhibition, and Carnwath’s recent interview with Michael Krasny on KQED’s forum.