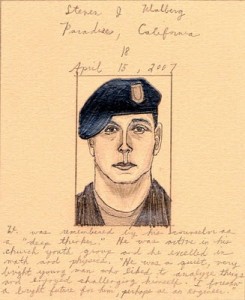

Emily Prince, detail from "American Servicemen and Women Who Have Died in Iraq and Afghanistan..." (from 2004, ongoing)

The numbers kept coming up in the daily reports. Five here, fourteen there, one day after another. And then the growing figure mounting over a thousand. Peripherally it was ever-present, but still only an abstraction. (Emily Prince)

Abstract art is the gift that keeps on giving. Just when serialism felt stretched to snapping point, along came Felix Gonzalez-Torres to re-jig the strategy in his endless stacks of stealable prints, infusing the tradition with a sad generosity. Monochrome painting looked to have painted itself into a corner, until Robert Ryman whipped it into shape, sergeant-major style. Geometric minimalism seemed spent before Eva Hesse replayed it in flaccid fiberglass. As in the Cubist bric-a-brac of the teens, these quasi-satirical take-offs proved the unexpected strength of the chosen medium by showing its capacity to accept transformation. Painting does this all the time. So too with Emily Prince’s new installation at the Saatchi Gallery, which co-opts hoary old modernist plots to create a new kind of anti-memorial, a multifarious monument of strange beauty and quixotic ambition.

Prince’s installation, which was featured in a slightly different form in the 2007 Venice Biennale, consists of thousands of portrait drawings on small (about the size of a cassette tape) rectangular pieces of brown, pink, and pale yellow paper, pinned to the wall according to a pencilled-on grid. You scan the images, pulled in by their tininess. Each drawing has its own legend, written in tiny cursive script: name, date, and place of birth and death, sometimes a character description. “He had wanted to enlist from the time he was 15.” “She was determined in everything she did in her life.” The installation is called American Servicemen and Women Who Have Died in Iraq and Afghanistan (But Not Including the Wounded, Nor the Iraqis, Nor the Afghans). There are 5,218 drawings to date, arranged, in this case, in chronological order of death. The grid has vacancies. Prince will continue to make the drawings in an endless edition until both conflicts cease, in a promise she might be regretting a bit.

Prince has explained (a little confusingly) her reasons for excluding the native dead – “I am an American. This is the material I’m allowed to work with” – but there’s something just a little bit McSweeney’s about that title, isn’t there, with its faux-naïve breathless tongue-tangling. This, I think, is Prince’s problem: how to square the earnestness of a straight-up archiving project – there’s a box of files displayed nearby, showing the cards filed away according to the subjects’ home state – with a kind of knowingness in the conveyance. From the press release:

…this ongoing memorial project brings attention to the human cost of war, turning statistics back into portraits of real lives sacrificed on the field.

And yet it’s the fact that they aren’t portraits – that they are, in a sense, abstractions, inevitably drawn from official photography – that lends the drawings their weird, distanced power. Drawn in “the skinniest, hardest lead I can find,” they’re based, for the most part, on headshots used for official purposes. Each sheet of paper apparently corresponds to its subject’s skin tone, although only in a pretty schematic way: there’s only one kind of dark brown, for example, and only a couple of different pinks, which somewhat defeats any claims for individualized portraiture implied in the press kit. Clearly, the installation owes a lot – might even be seen as an homage to – Byron Kim’s Synecdoche (recently acquired by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and discussed by Tyler Green in greater depth here), a wall of individual paintings reflecting a range of human skin tones, a somewhat heavy-handed spin on color-chart paintings by Gerhardt Richter and Ellsworth Kelly. Like Kim’s installation, Prince’s work might well be (pace Green) “not an important work of art” (there’s a can of worms for you), but may serve to “engage the most prominent American philosophical conversations.” For a British audience, the lack of dead native servicemen and women is an omission more poignant for its absence, bringing to mind Steve McQueen’s still-unrealized postage stamp project, Queen and Country, featuring photographs of dead British soldiers. (The petition, organized by The Art Fund, is growing in support and can be read about here; I wrote about this project for Art21 here).

Steve McQueen, detail from "Queen and Country"

Like McQueen’s mooted project, each of Prince’s images recalls the official portrait printed alongside the news report, jaw-clenched against a billowing flag. Positioned dead-center on each rectangular piece of paper, they have a formal, slightly abstracted stiffness about them, certain similarities provoked by a drawing style whose cuteness starts to elbow its way between the viewer and the reality of the dead person. After a while, the images become the same person, in and out of a helmet. You stop looking. The images return to an abstraction again. And this is how Prince’s installation works, articulating an earnest effort to empathize (that cursive!) while continually undercutting its ability to capture the dead person’s presence. Remembrance is a fight against abstraction.

Piero della Francesca, "Portrait of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza," 1465