As a northerner recently transplanted to the Greater Houston area, I admit to having reservations about all things Texan. I have found this a tough place to love at first sight. Yet, this particular region nurtures a unique host of fascinating figures and issues in contemporary art, along with sometimes frustrating contradictions and striking visual treats—including a wealth of handmade signs and arresting juxtapositions of natural beauty confronting the manmade. In this and subsequent posts as a guest blogger, I hope to sketch out some contributions to contemporary art made by the creators, institutions, and museum professionals who have chosen to either make their homes in and around Houston, or have come here to reflect upon the region in site-specific and installation projects. In the process, I will also reflect on some of the ethical issues in contemporary art that living removed from more established art centers has allowed me to better flesh out.

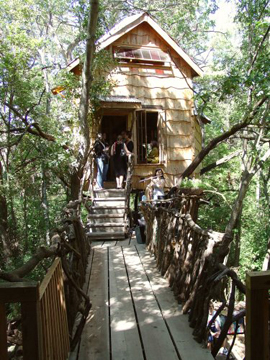

On my first trip to Huntsville, where I teach art history at Sam Houston State University, I was given a drive-by tour of several structures built by Dan Phillips and his Phoenix Commotion team. Intrigued by what I saw, I visited his “tree house” (where my colleague Annie Strader is the current tenant), and last December I invited Phillips to speak to my Contemporary Art class about his project. For the past twelve years, Phillips and members of the Commotion, including his wife Marsha, have been committed to building affordable and visually-distinctive housing out of largely post-consumption building leftovers, waste from the fabrication of industrialized materials (including “landscape timbers,” a plywood by-product), and other free or discarded materials. Examples of Phillips’s sustainable building aesthetic include: a roof made from recycled license plates, floors made from wine corks, an artist’s studio ceiling lined with salvaged picture frame samples, and a range of other less-than-perfect or blemished building materials destined for the landfill that have been recovered and put into unexpected, unanticipated use.

Since 1996, the Phoenix Commotion, a for-profit rather than non-profit organization, has completed thirteen structures in Phillips’s hometown of Huntsville. In 2004, Phillips, with the cooperation of the city, established a warehouse where recyclable building materials are donated, stored, and then accessed by charitable groups and low-income housing projects. To achieve their aesthetic and ethical goal of increasing the availability of out of the ordinary, low-cost housing in Huntsville, Phillips and his crew are not only building, but have also created an alternative infrastructure that enables materials typically considered building “wastes” or “leftovers” to be creatively reused by the community.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a9JkPk0CIo4]

In his process, Phillips employs an apprenticeship system to bypass the alienation typically associated with standardized labor, requires the assistance of the future residents of the homes in the construction process, and whenever possible utilizes and teaches craft traditions that have largely been displaced by mechanical means. Such choices are motivated by Phillips’s insight that the “gobs of waste” we are currently producing–including wasting the labor of perfectly capable local hands–are largely by-products of a cultural order that insists on equating beauty with perfect, standardized form. Phillips openly calls attention to the fact that such methods are not original and that they have been and continue to be used in communities where building by recycling is a necessity.

While Phillips could not be considered an art celebrity by the standards of international biennials and fairs, and demonstrates little or no concern with the vogues of the international art world, he has recently been enjoying generous national media attention, including an appearance on The Today Show and a September 2, 2009 article in the Home & Garden section of The New York Times. The Phoenix Commotion, which operates with a slim profit margin, has also recently expanded to include a Design Store. An overview of recent press and the completed and current Commotion projects are documented on the website.

In media coverage, Phillips is often explicitly and sometimes implicitly presented as an American “folk hero,” whose do-it-yourself building projects offer a tangible, workable solution to both the reality that the middle-class American dream of owning one’s own home is becoming increasingly out of reach and also to the current environmental crisis of overfull landfills and escalating chemical pollution. Admittedly I, too, am drawn to Phillips’s work for these reasons and am tempted to frame him in similarly heroic terms. In addition to his project’s ability to foster a true, sustained sense of community (no small feat these days), to promote an eco-friendly aesthetic, and to return a sense of control of one’s own environment to an immediate, local level in an increasingly globalizing world, Phillips and the members of his team are magnanimously generous and whole-heartedly committed. The Commotion’s enthusiasm for their work appears boundless and is contagious.

But while I appreciate the work of Phillips and Phoenix Commotion for all of these reasons, I am also struck by the relationship of their project to others that explore place-making as a theme and insist on entwining artistic processes with pressing local needs. In the follow-up to this post, I will elaborate further on some of these connections.

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog