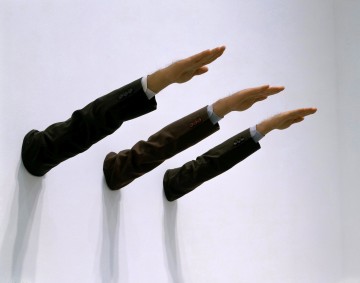

Maurizio Cattelan, "Untitled," 2003. © Maurizio Cattelan. Photo: George Hixson, Houston. Installation view, The Menil Collection, Houston, TX.

The current Maurizio Cattelan exhibition at The Menil Collection, Houston (February 12– August 15, 2010) marks the U.S. debut of recent large-scale works, site-specific installations, and four new works. Cattelan’s first solo show in this country since 2003 celebrates the artist’s return to sculpture after several years of publishing and curatorial work, including his 2002 co-founding of The Wrong Gallery in Chelsea, New York, his collaborations on Permanent Food (an occasional journal comprised of altered pages torn from other magazines) from 1996-2007, his co-editorship of Charley (a conceptual project and independent series on international contemporary artists) from 2002–present, and his curation of the Caribbean Biennial in 1999 and the Berlin Biennial in 2006. The notion of revisiting to give new life–suggested by Cattelan’s own turning back to his past artistic practice –is provocatively carried through the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue, Maurizio Cattelan: Is There Life Before Death? on a number of levels.

The exhibition consists of large-scale works first seen in Europe in 2007, along with recent sculptures, including works created in response to Cattelan’s site visits to the Menil that riff on the museum’s renowned Surrealist holdings. Organized by Franklin Sirmans, the Menil’s former Curator of Modern and Contemporary art, the exhibition juxtaposes a range of objects–mostly from the 1960s and 70s–that Cattelan, in collaboration with Sirmans, selected from the Menil’s large permanent collection. They are suggestively installed to create conversations with the artist’s own new and recent works. This installation strategy trips up the typical arrangement of a solo artist show—an arrangement that, more often than not, isolates the featured artist’s work from examples of artistic predecessors and contemporaries in order to foreground the sense of an internal, exclusively personal, development.

Rather than confining Cattelan’s artworks to a couple of galleries, the exhibition has examples of the artist’s works sprinkled throughout, even on the Menil’s main building. Some are buried in the intimate recesses of Antiquities and Surrealist galleries, others are more visibly displayed, including Cattelan’s Untitled (2003), depicting a “drummer boy,” which has been relocated from its usual position atop The Rachofsky House in Dallas to perch coyly upon the roof of the Menil’s Renzo Piano building.

The reinstallation of The Menil’s holdings as part of the exhibition sees prints by Andy Warhol mingling with works by Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, Bruce Nauman, Ed Ruscha, James Lee Byars, and Francis Bacon. Since Cattelan’s own artistic development was influenced by the Arte Povera movement in Italy, the exhibition also witnesses The Menil’s usually U.S.-centric installations of twentieth-century art edited and rearranged by Cattelan and Sirmans to now include significant works by the Italian conceptualist Alighiero e Boetti (on loan from a private collection), a mirror painting by Michelangelo Pistoletto (which until recently hung in John and Dominique de Menil’s Houston home), as well these artists’ forerunner, Lucio Fontana.

The Menil Collection offers the perfect site for such an artist-curator institutional intervention that has, at least since Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum, (1992-93) — Wilson’s collaboration with the Maryland Historical Society and the Contemporary Museum, Baltimore — enjoyed growing popularity among American contemporary art institutions (Wilson is featured in Season Three of Art:21). John and Dominique de Menil nurtured lasting friendships with several artists whose work they collected. They recognized early on that offering contemporary artists the opportunity to “raid” collections could give new life (and perhaps new cultural value) to art objects that are often stored in an institution’s tomb-like vaults or sequestered in the homes of private collectors. The collaboration of Sirmans and Cattelan, who together combed through the Menil’s holdings to gather objects for the exhibition and catalogue, harkens back to a show inspired by John de Menil. While touring the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum’s storage rooms in 1969, de Menil suggested that an artist be selected to “mine” the collection, taking on the role of curator. For that task he suggested Andy Warhol, whose resulting Raid the Icebox 1 with Andy Warhol was shown at RISD and subsequently at the Rice University Art Museum, an institution then run by the de Menils in Houston. Cattelan’s exhibition recalls not only that earlier example, but also the more recent exhibition of Robert Gober’s work in The Meat Wagon (2005; reviewed here). For that exhibition, Gober was invited by then-chief curator Matthew Drutt to assemble an exhibition that combined art and artifacts from The Menil Collection with his own work.

Maurizio Cattelan, "Ave Maria," 2007. Courtesy Danielle and David Ganek. © Maurizio Cattelan. Photo: Attilio Maranzano.

Cattelan’s exhibition deeply reverberates not only with the Surrealism in the collection and Wilson’s experiment, but also with the works of Warhol and Gober, who are well-represented in The Menil’s collections and whose earlier interventions still haunt its archives and galleries. The works of Warhol, Gober, and Cattelan recall the iconographies and rituals of Catholicism and mine its paradoxical reverence for and disavowal of the body with alternately light-hearted and chilling effects. Like Raid the Icebox I and The Meat Wagon–interventions that came before his own–Cattelan’s exhibition engages with themes of raiding, mining, and resurrecting, while circling around questions of life and death. In The Menil, the visitor becomes a player in a scavenger hunt to put Cattelan’s solo show back together again. The search offers up several works by Cattelan that tease with the promise of poetic transcendence, while others offer halting dead ends.

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Society of Contemporary Art Historians | Maurizio Cattelan

Pingback: Dissecting the Social Self: A [Wo]Man, an Animal, and an Ambiguous “I.” | Art21 Blog