I’ll agree with Ben Street who said in his recent post that there is “no consensus about the difference between ethics and morals, so let’s be broad about it.” This seems to be the most helpful way to have a constructive conversation. It also helps me to excuse why I’ll interchange the two throughout this text in the service of brevity. Also, in order to avoid an annoying series of additional caveats, I’ll note first off that I’m limiting my considerations here to art objects (which include video and film, in my opinion) and not performances or other such live actions.

Oscar Wilde wrote, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written.” Replace “artwork” where “book” appears and “made” where “written” appears, and you’ll have a concise summary of my answer to the question, “Must art be moral [or ethical]?” To suggest that “art” can be either ethical or unethical is to personify an object. We don’t talk about the ethics or morality of a hammer or an ocean. We may discuss the ethics of what humans do with a hammer or what they do to an ocean, but ethics are a means of measuring human behaviors. Therefore, it’s actually nonsensical to me to discuss whether an art object must be ethical or unethical. Art cannot be either. Artists can and, to my mind should, be ethical, being fellow human beings within a society, but “art” itself is not human.

Moreover, the subject matter of art cannot be considered “ethical” or “moral” any more than the object itself. All manner of abhorrent human behaviors are represented in artwork. That doesn’t make the work, or even the artist, unethical for tackling such subjects. We wouldn’t suggest that the painter who captures the extreme suffering of a brutal mass murder (clearly an immoral act), such as Picasso’s Guernica, had done anything immoral himself. Nor would we suggest that the act of painting The Rape of the Sabine Women was a good reason to arrest Jacques-Louis David or Nicholas Poussin. In my opinion, how true the representation seems (part of how high the quality of the work is) remains the only valid issue where subject matter is concerned. Is it well-made or poorly made?

Furthermore, even less savory subjects dealing with the unseemly sides of sexuality or human excesses are not in and of themselves immoral or unethical if they truly reflect a human reality. The failure to make such work well is condemnable, but not the task of creating work about something that most adults know all too well exists (despite the wishful thinking we often hear that not making such art somehow makes the behavior less real).

I’ve had similar discussions on my blog long enough to know that as soon as I suggest that no subject matter is immoral or unethical, someone will raise questions about art that was created through a process that hurt an animal or another human being. Usually in doing so, they’re conflating an individual’s (the artist’s) behavior with the resulting object of their process. Which explains why they tend to get very emotional and confrontational in response to my position. “He killed an innocent horse to make that video! What do you say about that, Mr. Open-mindedness?”

My response is that artists are as subject to the laws and customs of of their communities as any other citizen. If they break these laws, they are subject to the consequences of doing so. If they step outside the ethical customs, there will be repercussions. Making art is no excuse for breaking the law* or for unethical actions, but it remains important to direct one’s outrage at behaviors and not objects. None of this makes the resulting objects, which cannot abide by the norms or values of their community, “unethical.” It makes them an object that we can approach with all of our subjective criteria, to judge for ourselves whether we consider them well-made or poorly made, good art or bad art.

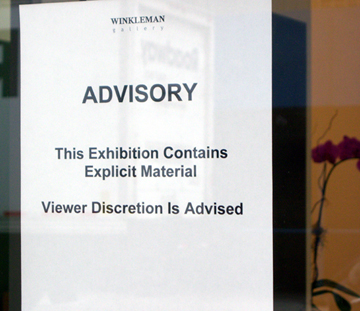

In my role as an art dealer, this issue sometimes comes into play while explaining what our artists create or the artwork we exhibit. Specifically, this opinion informs my position that I need not defend the subject matter in any particular work of art against charges that this or that art object is immoral or unethical. If a visitor to the gallery is offended by nudity, violence, or depicted behaviors within any of the works on the walls, it’s not up to me to convince them to open their mind to new adventures or think differently about this or that behavior (no more than it’s my role to tell an artist to close his or her mind or avoid certain subjects). My role is to explain to the visitor why I feel this artist has created something important. In short, my role is to explain why I feel it’s well-made…why it’s good art.

Of course, if a visitor still wishes to project his or her disgust at certain behaviors onto an object, there’s no way for me to stop him/her. I have heard some offended art viewers claim that certain works “glorify” immoral behavior by their mere existence. I would counter that, if made well, an art object stands just as much of a chance of discouraging immoral behavior. But, again, I’m not in the business of dictating which elements of human existence artists should or should not pretend doesn’t exist.

*Making art that challenges an oppressive law may be an ethical excuse for breaking the law, but still leaves the artist subject to the consequences of doing so.

Edward Winkleman is an art dealer and blogger who heads Winkleman Gallery.

Pingback: | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Week of Links 3/28/10 | Tomorrow Museum

Pingback: Unethical Art? « Art Becoming

Pingback: The Ring Festival and the Confined Deep | Art21 Blog