There is a budding tree branch that hangs right in front of my bedroom window. The buds are uniform and pop along the tree branch every two inches. And I look out through my bedroom window, which doubles as my studio, and I look out through my studio that doubles as my dining room, and I look out through my dining room that doubles as my living room, sitting on my convertible couch and watching the changing seasons.

From one position, a person has an endless chamber of perspectives. For me, I choose to reference landscapes in which I find geographic significance. Formally distilled characters are usually arranged in my work and their relationship to land depends on whether the character is consumed by the landscape, or is running from being consumed. The characters are usually searching for something, but don’t having the institutional memory to maintain this search. A type of amnesia, or erasure of tradition and culture, is what comes to my mind. When one is asked to migrate away from his or her original space, what happens? What do they take with them? My guess is what they can hold in hand: clothing, spirit, culture, religion, and memory.

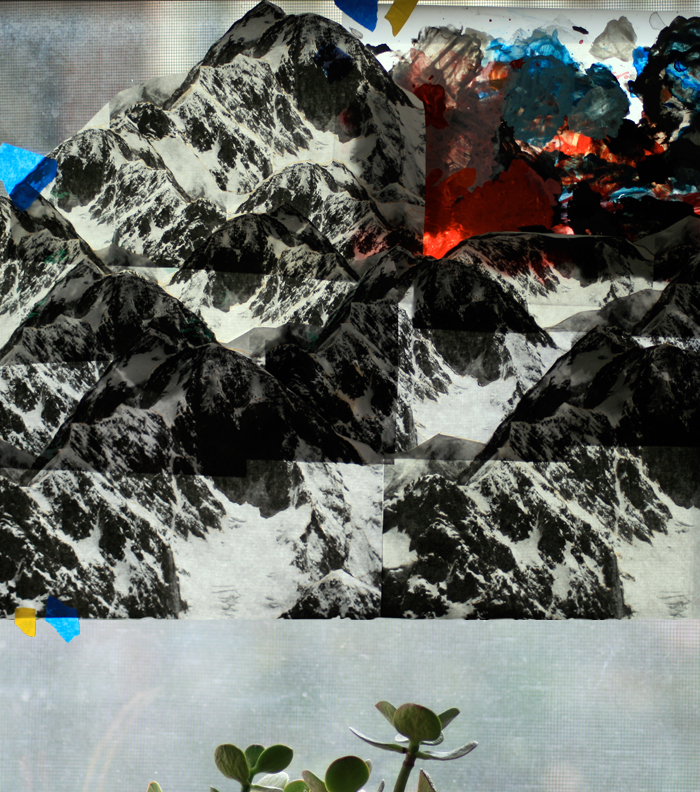

Lately I’ve used the Hindu Kush mountain range as an allegorical space for narratives that take on the role of searching. On a literal level, the Hindu Kush mountain range is a site where ethnic and political tensions arise because nobody is quite sure who, or what, belongs in that space. No one group can rationally claim ownership to that specific space, and as a result the boundaries that are carved, and decisions about who, and what, belongs in each place turn quickly to the absurd. Migrations, of culture and people, are often the result of absurd claims to an appropriated religious or culture presence in the space of places. The idea of borders, or boundaries and their translocality, or people living in liminal states, play heavily in much of my work.

I am now reading: Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger, by Arjun Appadurai.