London Mayor Boris Johnson, Olympics Minister Tessa Jowell, Lakshmi Mittal, and Anish Kapoor

Poor old Vladimir Tatlin. Having been ruthlessly picked-apart in numberless modernist critiques, his thwarted architectural ambitions have yet again provided the basis for a work of contemporary art. Anish Kapoor’s design for a monumental public sculpture for the 2012 London Olympic site, unveiled this week, is a sort of organic knock-off of Tatlin’s spiraling lattices of iron and steel. Kapoor’s signature maroon palette and bulging, squidgy forms – a catch-all code for blood and guts and sex and death and all the other big themes slapped onto the artist’s works in enthusiastic press releases – have been reconfigured into a huge spurt of latticed steel that loops around itself and culminates in a disc-like viewing platform. The sculpture – officially the ArcelorMittal Orbit, a car crash of corporate acronyms surely soon to be replaced with an architectural nickname (The Partially-Decayed Human Larynx, maybe) – will be Britain’s largest public sculpture, an accolade that sounds like an insult (like “Employee of the Month“) but is in fact the terms on which public commissions tend to define themselves these days, especially in the UK.

Lego "Angel of the North" at Legoland Windsor

No sooner had Antony Gormley’s enormous Angel of the North been installed back in 1998, than local government agencies started courting corporate investors for monumental works of art that would do for the 21st century what suspension bridges and railway stations did for the 19th: provide tangible and solid evidence of the country’s engineering prowess and international cultural standing. The problem remains that of art’s pesky inability to sit still and be about one thing. Bridges are bridges, whatever attributes they’re made to embody, and art’s semantic skittishness remains a stumbling block for public works of art. The Angel of the North could either be a monument to the virtuosity of the British steel industry or a memorial to it, a grounded and flightless epitaph. Kapoor’s tower could either be a celebration of national engineering innovation or a hubristic blast of Olympian pomposity and corporate extravagance that’s huge (a thousand times taller than the Eiffel Tower, or whatever) simply because it can be, not because it needs to be. To future historians in zero-gravity bubble-pods analyzing the artistic legacy of the twenty-first century, the blossoming of enigmatic public sculptures will seem as retroactively metaphorical as The Colossus of Rhodes or Nero’s own bronze Colossus, legendarily installed in the Forum and melted down in the fourth century to make coins.

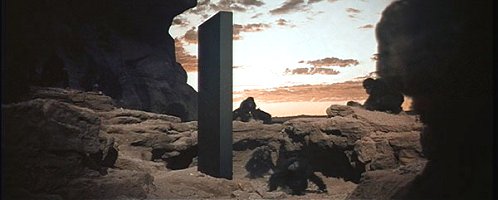

Still from "2001: A Space Odyssey" (1968). Dir: Stanley Kubrick.

Kapoor is probably the perfect choice for the job. Less self-absorbed than Gormley, less cautious than Whiteread, with none of Quinn’s or Hirst’s gross-out snickering, Kapoor’s work manages to accrue popular appeal while retaining a certain amount of critical regard, probably because his one-shot sculptures might as well be massive: there’s no delicacy lost in their inflation. His enormous work, Marsyas, for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall – drum-tight red rubber stretched over three elliptical frames – is still the best of the Unilever series of commissions for that space, since it shows an innate understanding of the basic requirement of very big sculptures — to give as many people as possible as awe-inspiring an experience as possible. The contemporary art world might turn its nose up at such an ambition, but it’s hard to grumble at the generous intention of such a work, a sort of Barnett-Newman-meets-James-Cameron approach. And Kapoor’s Tower, for all its unappealing anatomical aesthetic, does, in skin-crawling contemporary parlance, “tick all the boxes.” Its functionality as viewing platform and urban nodal point doesn’t compromise its artiness. It’s wacky in a palatable way, self-evidently “art”: without demanding you spend much time thinking about what it means.

There’s an interesting final parallel between Kapoor’s tower and Tatlin’s. The name ArcelorMittal refers to the conglomeration of corporate sponsors that have bankrolled its construction: Arbed, Aceralia, and Usinor (sadly not a troika of friendly trolls from The Lord of the Rings but three steel companies, two Spanish and one French) and Lakshmi Mittal, India-born steel tycoon and Britain’s wealthiest man. Kapoor’s sculpture thus becomes a sort of showcase of European industrial might, as Tatlin’s was intended to be for Russia. The wow-effect endemic to Kapoor’s most successful work locks in to corporate investors’ need to display the versatility of their industry; it’s about as win-win as patronage gets. And yet, like Tatlin’s tower, Kapoor’s work – which the artist claims is an attempt to “rethink what a tower might be,” an ambition you might also ascribe to the Eiffel Tower – smacks of the impossible. That massive corporate sponsorship will, however unintentionally, realize Tatlin’s hundred-year-old dream doesn’t make it any less hubristic, nor less suggestive of the fevered Baroque imaginations of despots unwilling to settle for second best.

Hollywood-style giant sign in Basildon, Essex