From "Torture of Women" by Nancy Spero, Siglio Press, 2010. Photos courtesy National Gallery of Canada.

“In our day, [when] we came back from war,” said Seymour Hersh to Bill O’Reilly in 2004, “We would take our pictures and hide them behind the socks in the drawer and look at them once in a while.” But this generation is different, Hersh lamented, appearing on Fox just after his infamous Abu Ghraib expose debuted in the New Yorker; this generation sends sensitive pictures around on CDs, uploads them to the Internet, and even sells them—God forbid—to news outlets. “Some kid right now is negotiating with some European magazine,” Hersh said, confident that the onslaught of Abu Ghraib visuals had only just begun.

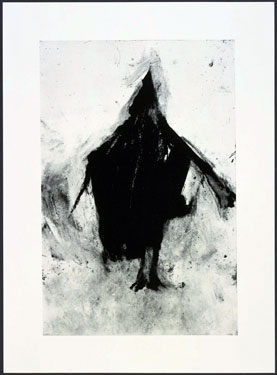

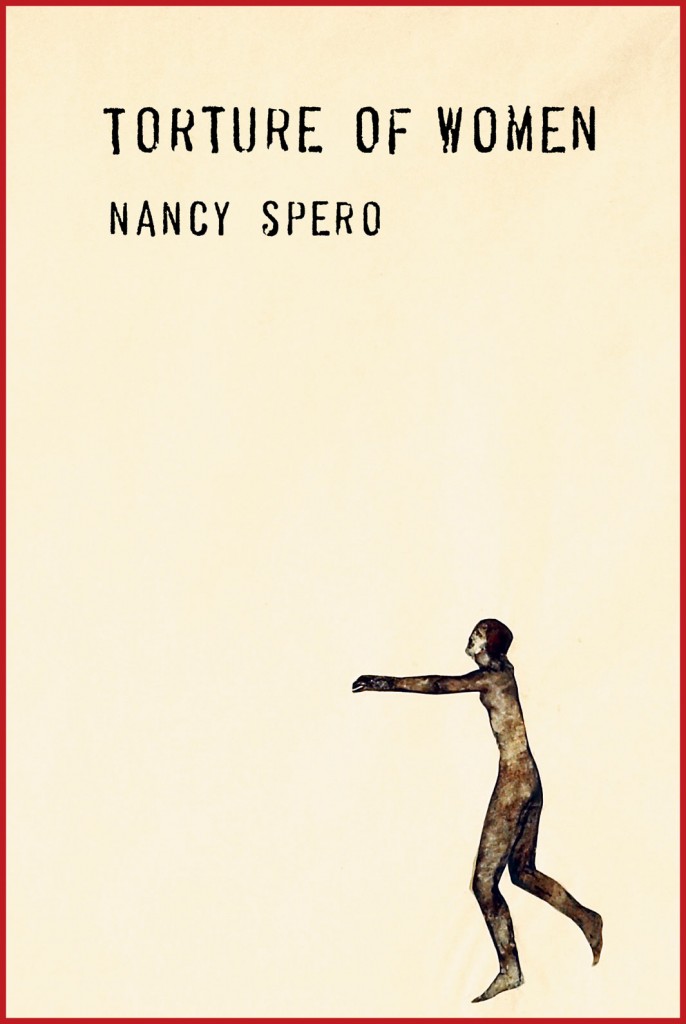

When Nancy Spero (Art:21 Season 4) began making her biting panoramas, war pictures were still hidden behind the socks in American bedrooms. The subject of torture seemed the ideal province for a socially driven artist who wanted to cut through the strange sheen of silence that surrounded political trauma. Spero, sensitive but unrelenting, was perfect to do the cutting. A new book by Siglio Press, out April 30, re-presents Spero’s often talked about yet rarely seen project, Torture of Women (1976) — 125 feet of drawings that pair accounts of female torture victims with willowy, mythical figures.

From "Torture of Women" by Nancy Spero, Siglio Press, 2010. Photos courtesy National Gallery of Canada.

In book form, Spero’s drawings are jarringly seductive, quaint like Henry Darger, pious like Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, and angry like Emma Goldman. They also look old. But their datedness may actually be the book’s greatest asset. Spero was quick to say that art should talk to its time and, though the subject of Torture of Women matters now as much as ever, a lot changed when photographs of torture catapulted out of drawers and into the blogosphere.

I first encountered Spero in the pages of Michael Kimmelman’s 1998 book Portraits, a down-to-earth take on the “artists-on-art” formula. Kimmelman joined Spero and Spero’s husband, painter Leon Golub, for a stroll through the Metropolitan Museum of Art and, in the resulting essay, Spero and Golub come off as two deeply conscientious artists. They apologize for resenting Pollock, talk about Tiepolo as if he were their contemporary, and praise one another’s subversiveness. Though they react to art viscerally, they care more about how it relates to the world than its identity as art. “Nancy and I are both content-oriented,” says Golub. “I have often thought of myself as a history painter and I think Nancy looks at things in a similar way.”

From "Torture of Women" by Nancy Spero, Siglio Press, 2010. Photos courtesy National Gallery of Canada.

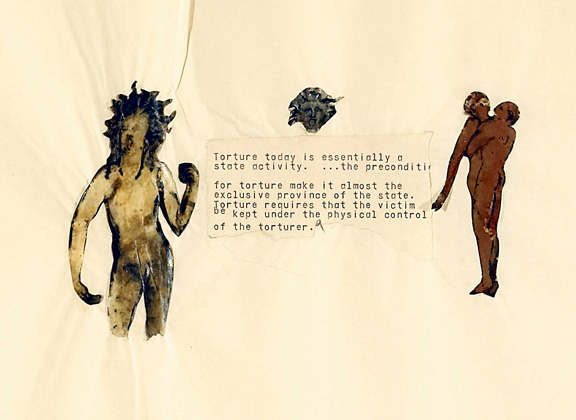

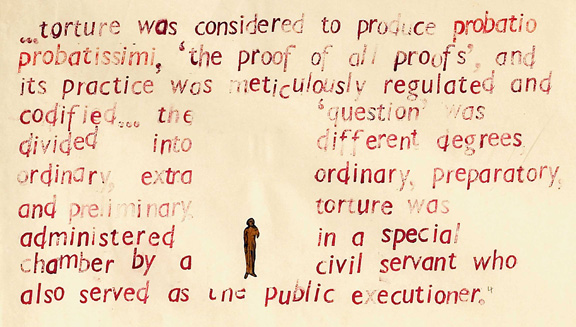

Torture of Women trolls two different histories — trauma narratives from Amnesty International’s 1975 report and a moment in the 70s when small, delicate, and brutal images were subversive. As close to an artist’s book as it could get without feeling precious, Torture of Women offers full views of each of the fourteen rectangular panels, and then zooms in so that each report can be read and each figure seen in detail. The barbarity of the text — all of which is typed, but differently colored, differently sized, and differently oriented — is hard to avoid when seen on a page: “as I hung half naked several people beat me with truncheons”; “they tried to force me to take medicine and eat. I was bleeding thick blood”; “large strands of hair had been pulled out.” The figures, some human and some animal, swim in and out of the words or stand alone against expanses of cream-colored paper. They don’t illustrate the testimonies. Instead, they echo the rhythm of the words, bending in uncomfortable ways, stretching across long pages or ending abruptly.

From "Torture of Women" by Nancy Spero, Siglio Press, 2010. Photos courtesy National Gallery of Canada.

The book includes a pithy yet astute essay by Diana Nemiroff; carefully curated excerpts from Elaine Scarry‘s dense, heartfelt book The Body in Pain (1986); and a disorienting short story by Argentinian writer Luisa Valenzuela. Nemiroff’s essay equates Spero’s project with witness-bearing: “Torture now is hidden, officially denied, invisible. The tortured have become disappeared. The absence of explicit images in Torture of Women echoes this disappearance.” The text in Spero’s panels brings “torture into the open, ruining its invisibility.” But invisibility has changed since 1976.

In Portraits, Golub and Spero talk about how the fragility of her work felt aggressive when it first appeared, and they cite Richard Serra as an example of what she subverted. “My work rebels about against very large paintings,” Spero says, “because I’m trying to break down the authority they imply.” After Abu Ghraib, Serra (Art:21 Season 1), whose steel monstrosities blatantly pitted power against vulnerability, felt compelled to compensate for his own formalism. He made dark renderings of hooded Abu Ghraib prisoners — a project about as trite as trick-or-treating as a ghost. It was disturbing, too, because it was Serra who thought representation was the way to react to the flagrantly graphic images coming out of Iraq.

Other contemporary artists have also explored erotically violent imagery that also recalls Abu Ghraib, intentional or not. Monika Majoli, whose Rubberman series depicted a hooded S&M-style figure bound in various uncomfortable ways that would have seemed Tarantino-esque a decade earlier, also now appeared to be rehashing Abu Ghraib repeatedly, even though she didn’t mean to. Thomas Hirschhorn’s post-Abu Ghraib collages juxtaposing couture, soft-core, and extreme violence aimlessly reiterate the same point Seymour Hersh made in 2004 — that images of torture and violence aren’t hidden anymore — but Hirschhorn, like most artists, doesn’t really know what to do about it.

Spero dealt with the invisible in a way that resonated in 1976 and continued to resonate through much of the 1990s. Now that torture has become visible in a new way, artists must remap the ugly gap between seeing and understanding. Torture of Women sets a precedent rather than a standard, like a manifesto from a previous era that upstart rebels pour over, even though they know their revolution will have to be different.