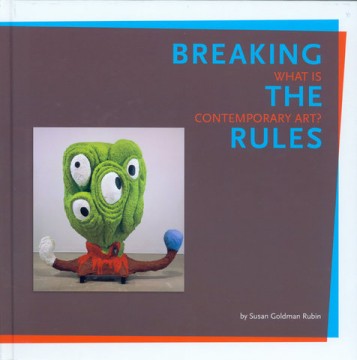

Last month, MOCA published a new book dedicated to engaging children with its permanent collection. Aimed at children age 8-12, Breaking the Rules: What is Contemporary Art? exploring works by 25 different contemporary artists, including Robert Rauschenberg, Charles Ray, Vija Celmins (Season 2), Gordon Matta-Clark, Barbara Kruger (Season 1), Gabriel Orozco (Season 2), and Mike Kelley (Season 3). The full-color pages include large images of each featured painting, sculpture, installation, or photograph, along with biographical information, quotations from each artist, accessible analysis of each piece, and engaging questions to help its young readers engage with the conceptual aspects of the work. I spoke with MOCA Educator, Juliana Romano, who conducts tours for visiting school groups, to get her take on the educational potential of the book, authored by Susan Goldman Rubin.

Lily Simonson: Can you describe your approach to guiding tours with groups of students?

Juliana Romano: We use a modified visual thinking strategy, which about a basic line of inquiry. What’s going on here? What do you see that makes you say that? What more can you find? For example when we were looking at Mark Tansey’s Triumph Over Mastery today, one student said, “that thing is broken.” So I responded by asking more questions: “What do you see that makes you say it’s broken?” Even though it’s obviously broken. That way, you get a more rich description. “It’s crumbled…” And you get closer to seeing what their assumptions are, and closer to having a breakthrough. We try not to be didactic. We draw out the students’ observations, and then we add onto it questions that are interpretive.

LS: Susan Rubin includes questions about almost every piece in the book. How do her questions compare to the types of questions you ask students in a discussion setting?

JR: The question she asks about Jim Shaw, “What does it mean?” is a really hard question. I might not ask that directly, even though that’s what we’re getting at.

The question about Mike Kelley’s cat shrine is more leading: “The very absence of the cats evokes sorrow. Was Kelley Seriously Mourning Their Loss? Or was he making a spoof of people who dedicate elaborate tributes to their deceased pets?” I like it because it really gets at one of the things I’m more challenged by, which is: how do you get viewers to consider the level of sincerity in the artist? A lot of kids have this thing about art expressing feelings. And it gets taught to them so young. This idea that art is creative and art is all about feelings gets repeated so much. It’s difficult to get to the place where art is more cerebral, that’s challenging.

LS: What kind of information is helpful?

JR: Everything she discusses in the introduction is great. This is all really true, that’s what’s good about it. It applies to institutional critique, etc. The quotes from artists are really great. I think that’s Vija Celmins’s quote — “Stillness is one of the pleasures of painting…it’s a surface that doesn’t move” — is terrific. It’s pretty abstract, I think that kids. I think it’s really deep and really important, but clear enough for maybe 5th graders to get.

LS: Maybe one thing that this book does is privilege the artist’s intention and tie the art into a larger biography of each artist. Do you ever try to give the students biographical information?

JR: I incorporate that information if the conversation is calling for it. It’s funny, because just last week we were touring each other to practice incorporating more biographical information. I toured William Kentridge for my coworkers, and spoke about his life, and in that instance it didn’t really help.

There are some pieces that need it more. Really you need it when you’re looking at something and people are saying ,“I don’t know if it’s art or not”… For example ephemera, performance, If a piece is not making sense to the group, and you’re trying to get people to look at it and they can’t look at it.

LS: It’s interesting that Susan Rubin did not just focus on the most well-known artists in the collection. Do you think the artists she chose are particularly engaging for children?

JR: Definitely. I think it’s great that she does a really good break down. I think the whole book is fantastic! I think it should get an A+. Just thumbing through it, it looks really good. It looks fun and appealing, and accessible. I like her conclusions about each piece. Her analysis of Charlie Ray – “as an artist he wants to puzzle viewers and challenge their perceptions of what is real” — is great because it’s so simple, but conveys the essence of the work.

It’s good to have a little summary of what the artwork is about up your sleeve. But I also think that’s not always what people want to know. They want to know something bigger. Why it’s art, what kind of art it is, why people make objects. Their questions are really big.

LS: I liked being on your tour, because I get disenchanted with the art world. They’re cutting all this arts education and sometimes I find myself questioning the value of it.

JR: Looking at contemporary art teaches so much, thinking critically, understanding images, knowing how to read our world of images – looking at a newspaper, or an advertisement, and knowing what you’re being told.

Looking at art is also really great for learning how to write. In the classroom, they’re taught how to make sentences, but it’s hard to teach how to have an idea, riff on it, back it up. Analyzing art helps them learn how to build an argument and have a point of view that’s different from somebody else’s. And whether or not they’re aware of it, they ran the tour so they feel ownership and ability to do it on their own.

This book ultimately does the same thing that we try to do. To make people feel like they can get it.