Eva and Franco Mattes aka 0100101110101101.org with their avatars in Plymouth, UK. Photo by Marco Anelli.

The Italian “artist-provocateurs” Eva and Franco Mattes, aka 0100101110101101.org, are no strangers to this site. Our very first guest bloggers back in 2008, when they blogged about their Influencers festival (more on that below), they have since made semi-regular appearances in this column.

Throughout their practice, the Mattes seek to make the invisible visible, under rather clandestine circumstances. From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, they operated under the name Luther Blissett (1994-99) with a collective of other artists. Notorious during this time was the figure of Darko Maver (1998-99), an imaginary Serbian artist they invented only to “murder” him soon after. The Mattes then became known for their culture-jamming projects like Nike Ground (2003), in which they convinced Vienna residents that a public square would be renamed “Nikeplatz”; Vaticano.org, their hacking of the Vatican’s website; and Life Sharing (2000-2003), a net art project that allowed anyone in the world to log on to their computer and access their personal files.

Significant in the context of this column is the Mattes’s involvement with Second Life. 13 Most Beautiful Avatars (part of their larger Portraits project from 2006-7) is a photographic series of “celebrity” avatars exhibited in a contemporary art gallery in Second Life. Directly referencing Warhol’s 13 Most Beautiful Women and 13 Most Beautiful Boys (both 1964), these images transpose the banality of celebrity and human desire onto the two-dimensional avatar. Around this same time, the Mattes began an ongoing series called Synthetic Performances (2006-present), in which their avatars reenacted seminal performance artworks in Second Life, including Marina Abramovic’s and Ulay’s Imponderabilia (1977), Joseph Beuys’s 7000 Oaks (1982-87), Gilbert & George’s The Singing Sculpture (1968), Valie Export’s Tapp und Tastkino (1968), Vito Acconci’s Seedbed (1972), and Chris Burden’s Shoot (1971).

While the Mattes continue their Second Life explorations, they have since turned away from reenactments and appropriations to produce original artworks in this virtual world. At the same time, their real-life practice thrives. With a solo exhibition of mostly new work, Reality is Overrated, currently on view at Postmasters Gallery in New York, the Mattes continue to create their provocative art with the distinctly twenty-first century variable that is the Internet. In doing so, they effectually sew the gap between art and life with the thread of the programming code.

On the occasion of this exhibition, I interviewed Eva and Franco about this show, their latest performances, and the promise of our latest procrastinatory tool, Chatroulette.

Kelly Shindler: Last time you spent time on our site, you were chronicling the 2008 Influencers Festival. Since then, there have been two more installments. Can you recap these two versions, explaining a little about how the festival has evolved over time? What inspired you to found the festival in 2004, and what role do you serve now?

Eva and Franco Mattes: We created The Influencers festival because there were so many amazing artists and “experimenters” out there that didn’t fit into traditional art spaces or existing categories. We wanted to meet people who had a big influence on our work, like the NSK, Joey Skaggs, or the Critical Art Ensemble, and give visibility to young crazy creatives like Molleindustria and Ztohoven. Plus we come from net.art, where festivals have been such an important element to create the network.

This year, about 3,000 people showed up over three days and we had some of the funniest moments ever. The IOCOSE group mounted a guillotine inside Ikea, as if it was a new product, and a Bike Kill was organized — a super weird out-of-the-junkyard bikes joust with the amazing guys of Black Label Bike Club and several bike groups of Barcelona. So many people participated and everybody got hurt. The Yes Men were there in their Survivaballs giving an great lecture (picture 1,000 people singing Exxon’s musical, “Up Came Oil!”) and we got the chance to know the astonishing work of “radioactive sculptor” James Acord. For the next years, we are planning more and more actions…

Eva and Franco Mattes's "Synthetic Performance" of Chris Burden's "Shoot," 2007. Courtesy the artists. Photo by Marco Anelli.

KS: I’m glad to see that your Synthetic Performances series is still ongoing, with new performances taking place at Performa09 and two new works in collaboration with Plymouth Arts Centre, through a project organized by Marina Abramovic, earlier this year. Tell us about these new works. Do they differ from your earlier reenactments at all?

E&FM: Our recent performances are no longer reenactments of historical performances but new pieces. One of them is I can’t find myself either, where Eva and I were laying naked on a bed and people could join us with their avatars and take part of what should have been an orgy but turned out to be a somehow ominous 3D-bodies-merging freak show. Another new piece is called, I know that it’s all a state of mind, where Eva and I keep falling over and over for hours. This was not meant to be participatory but after a while, other avatars from the audience started falling down too and kept doing it till the end of the performance. Doing performances in Second Life now is much more interesting than it was in 2007. Now avatars are super fast at improvising with you; the result is, of course, unpredictable.

For Marina, a crucial element of performance art is endurance so we accepted [the directive] to perform for four days, four hours a day. At the end, we were almost throwing up on keyboards and for the first time, we felt the pain that our avatars usually don’t feel in our performances.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sTQPZhre50g]

KS: That does sound nauseating. What marked the shift from reenactments to these new original performances?

E&FM: While working on the reenactments, we realized that some of the best moments were software errors. For example, bodies were merging into one another. It shouldn’t be like that and sooner or later, they’ll fix it. So we got interested in these errors and thought that a “videogame-native” performance should work on this and include software bugs. We’re not playing the computer like you play a guitar; we’re playing with the machine, we get influenced by it. The computer is not an instrument; it’s more like a partner.

KS: And what inspires you to continue to situate them in Second Life? In other words, what is the continued draw to performing in Second Life for you?

E&FM: We are trying to figure out how to use videogames in general, not only Second Life, as performance platforms. Performances in videogames are, one would say, all appearance and no substance. But in fact, it’s the other way around. In a world where you don’t see the “real” appearance of a person — age, skin, voice, clothes — what’s left for you to judge him is what his brain can generate. In videogames, you’re dealing with brains without a body, and I like brains better than bodies.

Eva and Franco Mattes aka 0100101110101101.org, "Karee Kayvon," 2006. Digital print on canvas, 36 x 48 inches. Courtesy Postmasters Gallery and the artists.

KS: This question is quite simple and perhaps a banal one. But it is important in the context of this Art2.1 column. What differentiates your work in Second Life from your art projects in real life? There is also a blending of the two, as in your avatar portraits series, where you bring Second Life avatars into the physical commercial gallery…

E&FM: Although our “online” and “on the road” works may seem very different, it’s what they have in common that’s interesting to us. For example, the fact that they are set outside traditional art spaces, be it a square or the Internet, and that they aim at a different audience [rather than] the traditional “art” one, sometimes involving people who are totally unaware of being part of a work of art. Nike Ground, for example, is a fake Nike advertisement campaign, a big performance that took over an entire square in Vienna, while Biennale.py is a computer virus that we created and spread, a work of art that comes directly to your home.

Eva and Franco Mattes aka 0100101110101101.org, "Fake Nike Infobox," September 2003. Various materials, 611 x 548 x 550 cm. Installation in Karlsplatz, Vienna. Photo courtesy Public Netbase and the artists.

KS: Yes, there’s definitely a connection here — the Internet constitutes one kind of public space, whereas the proverbial public square constitutes quite another. These two works you bring up are very much about the potential of the viral – whether it’s hackster misinformation or an actual computer virus. And, I would venture, they incorporate a political dimension as well. What kind of virtual and bodily publics are you trying to engage and how do these various modes of address achieve that?

E&FM: In our best dreams, we are making art for the person next door. I’m not sure if we achieved it though.

KS: Recently, I just had my first experience with Chatroulette “art.” I am wondering what your thoughts are on it as a potential artmaking tool. In a way, it involves avatars too — but with more realistic bodies that are also often naked…

E&FM: When net.art started, we were all blown away by the idea of having a sort of personal live channel accessible to anybody in which putting our things, but in the mid 90s, this was very abstract and rudimental — the Internet speed sucked. When we did Life Sharing and put all the contents of our home computer online and shared them with everybody, we were like cavemen trying to make art with bones and stones, stoned. Now platforms like Chatroulette give everybody a live channel that is much more sophisticated, a sort of TV made by everybody for nobody. We recently worked on a project that used one of these online chat platforms but this time, instead of living online, we are trying to die online.

KS: You’re talking about your new work, No Fun (2010), in which Franco dangled from a noose for hours, witnessed by scores of Chatrouletters in various states of shock and disinterest. While broadcast on the Internet, it featured his actual body, rather than that of an avatar, and it was quickly banned from YouTube. You also just resurrected a “lost” work, Stolen Pieces (1995-7), in which you two nicked small components of major artworks; the series is just now being shown for the first time in your Postmasters show. I’m sensing a leitmotif here. Whether you’re working with bodies, objects, pixels — how do you imagine life after death?

E&FM: Stolen Pieces is not exactly a “lost” work. We deliberately waited 15 years to show it. We planned to reveal it after our deaths, but we somehow miscalculated time. We were 19 years old back than and only recently we realized that it would have taken too long to die. The idea that there’s some sort of life after death is probably the biggest prank ever pulled. Bodies as well as objects decay and disappear at one point. Ideas and myths last much longer.

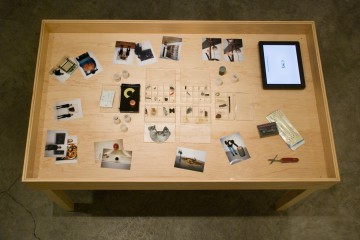

Eva and Franco Mattes aka 0100101110101101.org, "Stolen Pieces," 1995-1997. Mixed media objects, unique installation. Courtesy Postmasters Gallery and the artists.

Eva and Franco Mattes’s exhibition, Reality is Overrated, is on view at Postmasters Gallery (459 West 19th st., New York) until June 19, 2010.

Pingback: rebel:art » Blog Archive » Und sonst so? : 29. 05. 2010

Pingback: Letter from London: Interview with Aaron Moulton (Feinkost, Berlin) | Art21 Blog

Pingback: A New Days Work » No Fun (2010)

Pingback: Eva & Franco Mattes | thecontent

Pingback: Private vs. Public | Open Source Studio

Pingback: Introduction | Open Source Studio

Pingback: The 3rd Place: Hybrid Space | Open Source Studio

Pingback: asdfghjkl