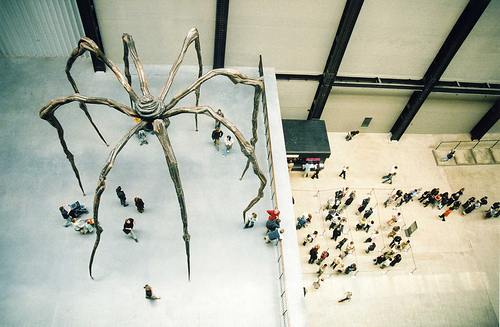

Giant spider sculpture "Maman" by Louise Bourgeois at Tate Modern Art Gallery, London. Photo by Steve Greaves.

There’s a display outside one of the shops in Tate Modern, showing visitors’ comments written on little cards. That visitors’ comments are encouraged at all, let alone actually displayed in the museum, is testament enough to the transformative effect that this institution, now in its tenth year, has had on the British cultural landscape. One comment, though, in bubbly, fourteen-year-old girl writing, catches the eye above the others. It reads (with spelling errors intact): “This museum rocks! It’s soooo AWSOME!” So far, so fourteen-year-old girl. But the next bit made me laugh, then think a bit: “I hope all the artists are going to be famous one day!!!”

You almost don’t want to disavow this young visitor’s enthusiasm: clearly the works she saw (Picassos, Bacons, Richters and Rothkos) had such an immediate impact on her that they obviously were by young, upcoming, anxious artists, rather than the hoary behemoths us jaded types have stopped really looking at. My first really transformative art experiences were at the Tate, too, though in its original incarnation across the river (what’s now Tate Britain), where I saw, as a teenager, works by Bacon, Miro, and Pollock that absolutely defined what I wanted from art: a kind of visual equivalent for the outsiderish obstinacy I sought and found in music. That’s not the case now – I subsequently found an interest in milder, older art, and milder, older music – but it’s worth, I think, remembering the immediacy of that initial lapel-grabbing, electrical charge when you can. Modern art – let’s face it – will always be cool in a way that contemporary art isn’t. At Tate Modern, it’s the modern displays – the salon-hung Surrealism room, the Bacon and Picasso face-offs – that remain permanently abuzz, while the huge Beuys installation, or Arte Povera room, are as forbiddingly depeopled as towns in Western movies with a creaky saloon sign and skittering tumbleweed. Maybe the museum’s disingenuous name says more than it realizes.

Joseph Beuys, "Lightning with Stag in its Glare" (1958-85)

Over the last decade, Tate Modern has, willfully or not, engendered cultural events in Britain that bear its unmistakable hallmarks of accessibility, participation, and slightly irritating chumminess. From Antony Gormley’s Fourth Plinth project, to the increased popularity of the Turner Prize and the reality TV show School of Saatchi, Tate Modern has permanently transformed the national interest in modern and contemporary art. 5 million people visit every year; it’s rarely not heaving with visitors. And there is an amazing diversity of work displayed. On a recent visit, I saw art by Luciano Fabro, Marisa Merz, Lucia Nogueira, Frédéric Bouabré, and Magdalena Abakanowicz – some demanding, difficult work – nestled among the crowd-pleasers by Dali, Kapoor, and Bacon. Fantastic, in-depth installations of photography by Bruce Davidson and August Sander are wonderful small exhibitions in themselves. Only a dyed-in-the-wool art snob would balk at such generally undershown work being exposed to such a huge audience. Without Tate Modern’s indisputably daring curatorial policies – enabled, almost certainly, by an extremely patchy historical collection that renders straight chronology more or less impossible – a huge swath of artists largely alien to the orthodoxies of art history would be little known.

Yet Tate Modern’s legacy is not really in its catholic curatorial approach, nor in its largely excellent exhibitions program. It’s in its transformation of visitor expectations of works of art, the connotations and fallout of which haven’t always been entirely positive. The Turbine Hall commissions, presented in the liminal zone between orientation point and the gallery proper, have all taken one of two approaches towards the cavernous space: either somber grandiosity (Miroslaw Balka, Juan Munoz, Rachel Whiteread) or fairground frivolity (Carsten Höller, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Olafur Eliasson). The problem remains that the expectations created by this prolegomenous showcase create unsustainable expectations within the gallery spaces themselves. The Tate’s pretensions to democratic openness – supported by cutesy sans-serif institutional font, passive-aggressive signage written as love letters (“Love Tate,” they read, excruciatingly), and a patronizing historical timeline with the charmless self-consciousness of one of Madonna’s children’s books – aren’t borne out by the poker-faced academicism of the collection displays. Thus you can slide down a twisty slide, buy a T-shirt that reads “Masterpiece” and send a video message to your mates, then walk into a room and contemplate 70s conceptual landscape photography by Robert Smithson and Keith Arnatt. That jarring contrast bespeaks a craven desire to please everyone, from the one-off visitor in high-vis GoreTex to the somber academic in ironic strongman moustache. It also foregrounds the general experience over the specific, something Tate Modern seems determined to do, often at cost to meaningful art experiences that it might otherwise provide.

In a recent article for the Telegraph, Alain de Botton claimed that, “It is a guilty secret that the art at Tate Modern is entirely secondary [to the architecture].” He’s right. I walked through nine consecutive rooms in the museum this week without seeing a single museum guard. (From what I saw, there were three guards posted in each ‘wing’ of the museum; that’s three guards for twelve rooms of art). What if you want to find something particular? I thought, who would you ask? But then at Tate Modern you don’t do that: you just stumble through, wowed by the experience, as the curators do their mix-and-match ADHD thing all over the walls.

Several rooms bear out the idea that the experience of the room prefigures the experience of the work. In one, for instance, a display of lush, early 20th century figurative work by Munch, Bonnard, and Modigliani is interrupted by the apparition of three thrust-out mannequin arms, doing Nazi salutes, set into the wall. It’s a work by Maurizio Cattelan entitled Ave Maria. Its presence there is meaningless — all the works were produced well before the onset of WWII, and none of the artists (with the exception of Picasso, whose blue period portrait of a woman is displayed here) either dealt with the war in their work, or played a significant part in it. It’d be hard to cobble together a more apolitical group of modern artists. And yet the curators persist in attempting to justify the intrusion of the Cattelan on the grounds that it is “a reminder of the horrors that would be unleashed in the decades to come.” I challenge anyone to read that without feeling they were being talked down to. That’s a recurrent feeling in Tate Modern.

Tate Modern took a gamble in undermining institutional authority through curatorial policy – something its apparent rival MoMA sought to emulate in its pilloried thematic hang, Modern Starts, in 2000 – and in terms of visitor figures that gamble paid off in an unprecedentedly successful way. It’s extraordinary that a museum of modern and contemporary art is one of Britain’s most popular tourist attractions, and that it remains a draw for both tourists and the art world in-crowd, the GoreTex and the strongman. And yet in order for the Tate Modern to truly compete in the pantheon of modern art museums – an aim surely underlined by its encyclopedic exhibitions schedule, from Futurism to Dada to De Stijl – it needs to allow its visitors to experience modern and contemporary art not as an ahistorical free-for-all — inquiry-based learning made concrete — but rather as something as deserving of contemplation and scrutiny as anything in the National Gallery or British Museum. This means a different and more daring approach to installation that privileges historicity over dissonance, the artist over the curator, looking over seeing. Those experiences many of us valued as teenagers – “I hope all the artists are going to be famous one day!!!” – were, after all, not made by the museum, but by works of art. How poignant that is, really.

Pingback: Letter from London: Public Enemy | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Henry Ford Letters To Louise Marshall | FordPhotosBlog.com

Pingback: HENRY FORD LETTERS TO LOUISE MARSHALL | World Car Blog