“We lay hold of the full import of a work of art only as we go through in our own vital processes the processes the artist went through in producing the work. . . . For to perceive, a beholder must create his own experience. And his creation must include relations comparable to those which the original producer underwent.” — John Dewey, Art as Experience

For Dewey, the perception of a work of art resembles the creative process. As a gallery director and as an educator who believes that it is my job to give non-specialists the tools they need to approach contemporary art, I find Dewey’s claim both provocative and, to a certain extent, unsettling. If you take a moment and think about the creative process, the energy and investment it takes, the surprises and even the frustrations that are inherent to any creative endeavor, Dewey’s seemingly innocent claim becomes a challenge. “Appreciation” is clearly an inadequate term to describe what Dewey believes viewers should do when they encounter an artwork. What, then, should we be teaching students who wish to engage contemporary art?

I am particularly interested in what Dewey calls the problematic phase of the creative process, and how that might find a parallel in a viewer’s experience. Dewey asserts that the artist “does not shun moments of resistance and tension”; rather, she “cultivates them for…their potentialities” because “the movement of passage from disturbance to harmony is that of intensest life.” Compare this to Bridget Riley’s recent description in the London Review of Books about her drawing process: “For me, drawing is an inquiry, a way of finding out – the first thing that I discover is that I do not know. This is alarming even to the point of momentary panic. Only experience reassures me that this encounter with my own ignorance – with the unknown – is my chosen and particular task, and provided I can make the required effort the rewards may reach the unimaginable.” This panic-inducing encounter with the unknown is essential to the creative process (as Riley calls it, “my chosen and particular task”). Building on Dewey’s claim that engaged perception is analogous to artistic creation, I’m suggesting that it is equally essential to the viewer’s experience of a work of art.

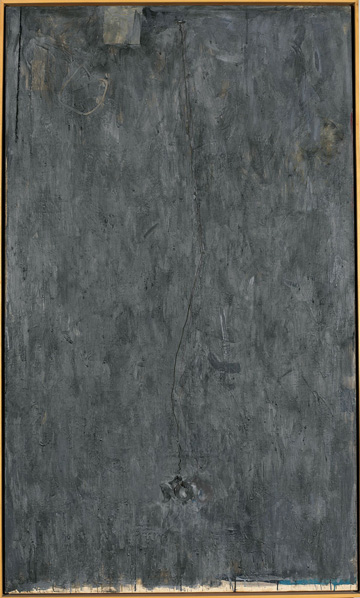

Jasper Johns (American, b. 1930). "No," 1961. Encaustic, collage, and Sculp-metal on canvas with objects. 68 x 40 in. Collection of the artist / © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Last weekend in the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art, I had an encounter with a Jasper Johns painting that provides not so much an example (that would take too long to describe) but an allegory of what I’m talking about. From across one of the modern/contemporary galleries, I saw a largish slate-gray canvas with an irregular, painterly surface. As I approached the piece, I noticed what looks like a crudely straightened length of clothes hanger wire, hanging from an eye screw in the top center of the canvas. Dangling from the bottom of the wire, camouflaged the same color as the canvas, was the word “NO.”

I’m suggesting experience—deep, transformative engagement with a work of art—begins with this “no.” It’s when the work challenges us and resists our habitual ways of seeing and understanding. As Dewey puts it, “‘taking in’ in any vital experience is something more than placing something on the top of consciousness over what was previously known. It involves reconstruction which may be painful.”

This poses a problem. We’re educators. We dispel ignorance and disseminate knowledge. How do we overcome what Robert Morris has called our “linguistic hysteria,” the understandable urge to settle the unsettled viewer with explanations? (Morris is referring specifically to wall texts.) How do we respect or even encourage the unknowing that may be essential to the meaning (to use an imprecise term) of a contemporary work of art? Thinking in terms of my encounter with John’s painting, how do we resist the urge to translate prematurely the work’s “no” into a “yes”?

I don’t have a specific answer to these questions. But it seems to me that one gift we can give students—and Dewey would say we’re all students—is a certain comfort with unknowing that will allow them to experience works that they may have otherwise been deemed as inaccessible. For example, the discomfort one might feel when seeing Bruce Nauman’s Clown Torture, or sitting across Marina Abramović at her recent performance piece at MoMA, is not so much a problem but the point—or at least part of it.

In the introduction to his book on Shakespeare, Stanley Cavell suggests that he needs to “cultivate his perplexity” with regard to plays — that is, overcome his complacent understanding of these canonical works, and see the plays in their essential strangeness. This is our unexpected task as educators: not only to discourage casual dismissal, or — worse — facile understanding of artworks, but also to help viewers engage a work in a way that respects its mystery and capacity to change us — in short, to cultivate our students’ perplexity.

Criticism, its role and its future, has been a topic of discussion of late. It’s no surprise Dewey saw its role as educational, and it seems that what he says about the critic’s “office” applies equally to education and how we introduce viewers to art:

Ty Clever is the Arts In Education Program Director at Millersville University, in Pennsylvania.“The moral function of art itself is to remove prejudice, do away with the scales that keep the eye from seeing, tear away the veils due to wont and custom, perfect the power to perceive. The critic’s office is to further this work, performed by the object of art. It is the critic’s privilege to share in the promotion of this active process. His condemnation is that he so often arrests it.”