With our poor economy and tough times in general, it would be natural for artists to look ahead to happier days. Like the rest of us, they are frustrated, and probably wish they could sell some more work. However, artists continue to deal with the past. They are looking back to difficult times, and making art that expresses fear, anxiety, and sadness stemming from events in their own lives as well due to world events like war, genocide, and state-imposed repression.

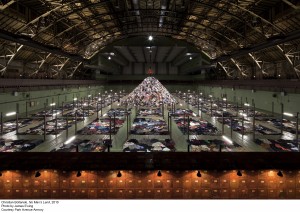

At the Park Avenue Armory, French artist Christian Boltanski recently mounted a large-scale installation called No Man’s Land, for which he assembled a giant heap of clothes in the center of the 55,000 square-foot Drill Hall. This mountain was surrounded by 45 rectangles—“plots,” the release calls them—of jackets and coats neatly laid out on the floor. Throughout these plots, anonymous poles played the sound of hearts beating—each one different, and taken from Boltanski’s ongoing heartbeat collection project, Les Archives du Coeur. At the front of the Hall, an intimidating arrangement of oxidized biscuit tins formed a towering 66’-long wall halting a visitor’s entry into the large, dim space and forced him to consider a path left or right to get inside.

The Holocaust connections seemed to be everywhere. Boltanski’s 40-year career has been absorbed with the Shoah, and he is known, to a certain extent, as a Holocaust artist. Born in occupied Paris in 1944, Boltanski grew up in postwar France. It was not only the pile of clothes in the center of the room that was reminiscent of victims forced to part with their packed belongings upon entering concentration camps, but also the rectangles of clothes on the ground and the steel beams holding up the heartbeat speakers that suggested the blocks of a camp. The sounds of the anonymous heartbeats reverberating throughout the old-fashioned Drill Hall and the massive amount of objects belonging to unseen people call the extent and anonymity of the Nazi genocide to mind.

Working with the postwar Germany of her youth, Elisabeth Smolarz has made a three-channel video installation currently on view at Kunsthalle Galapagos called Farewell East Germany. The history of East Germany is partly the history of the artist: Smolarz’s family immigrated to West Germany in 1989 from Communist Poland, where she experienced food shortages and hours of waiting in line for basic items. Through re-enactments caught on her video camera, Smolarz depicts three scenarios related to communist East Germany, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), and she also taps into “Ostalgie,” the nostalgia many former-East Germany residents continue to feel for the “good old days.”

In the first video, a middle-aged man named Uwe B. sings songs and recites poems he learned as a schoolboy. Though he is German, these are delivered in Russian, the language of this man’s East German youth. In the second frame, the camera slowly pans the library of the former Manhattan home of the West Germany’s ambassador. It was in this room that leaders from West Germany and the Soviet Union purportedly planned the demise of the GDR back in 1989. In the installation’s final segment, Peter S. attempts to disassemble and reassemble an AK-47 rifle while blindfolded, a skill he learned as part of his compulsive military service for the GDR. Smolarz chose to represent these two men because to her, they represent typical former citizens of the GDR. In an email message Smolarz noted that, “symbolically I found the language and the military service reflected the influence Russia had on the Eastern Block best.”

Lastly, the Guggenheim Museum’s new photo and video show, Haunted, is a composite of art from the museum’s collection dealing with memory and the feeling of being haunted by the past. Divided into four parts: Appropriation and the Archive; Landscape, Architecture, and the Passage of Time; Documentation and Reiteration; and Trauma and the Uncanny, the works incorporate original and archival material and deal with both personal memories and artists’ desire to bear witness and keep traumas from the past alive.

The types of memories range widely. There is a set of beautiful seascapes by Hiroshi Sugimoto, offering a sense of timelessness in nature. Sugimoto is also represented by a picture of a drive-in movie theater, a relic of past decades. In An-My Lê’s series Small Wars, men are shown reenacting battles from the Vietnam War. Lê’s photographs show the war through her modern eyes; her memories are likely tainted from outside sources like articles and movies of the period and the pictures were taken in Virginian forests instead of in Southeast Asia. Lê is working with photography’s evidential quality, the impression of authenticity the medium gives.

This spate of exhibits brings Roland Barthe’s Camera Lucida to mind, particularly his interest in photography and death. Likewise, these works have been inflected with memories and thoughts—often related to death—that have stayed with their artists. Perhaps this desire to engage memories—some unpleasant—and make work that is not only difficult to produce but also to view is a reminder that though things are bad, they could indeed be worse.