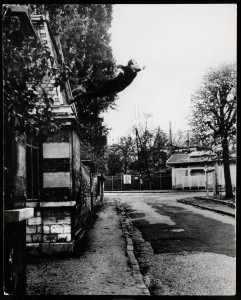

Yves Klein, “Obsession de la lévitation," 1960. Private Collection. © 2010(ARS), NY/ADAGP, Paris. by Shunk-Kender, © Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, courtesy Yves Klein Archives.

The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. is currently showing the first Yves Klein retrospective to hit the United States in nearly 30 years. Called Yves Klein: With the Void, Full Powers, it was co-organized with Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center. The show traces Klein’s evolution from monochromes to his Anthropometries and Fire paintings in nearly 200 works of art.

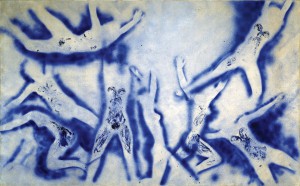

As an artist, Klein distanced himself from the strict confines of painting. Instead of conceiving of ideas to paint figuratively or abstractly, his plans were more along the lines of body painting and air architecture. Early on, he invented his own shade of ultramarine blue, called his International Klein Blue, which was inspired by a blue he saw used in Assisi by the Italian fresco painter, Giotto, in the Basilica of St Francis. Klein, in his desire to step away from the canvas, was an early performance artist. He was likely inspired by American abstract expressionists, but he took the performative aspect of artistry a step further; the making of his art was often a public spectacle.

Klein and a model during the performance "Anthropométries de l'époque bleue," 1960. © 2010 (ARS), NY/ADAGP, Paris. Photo by Shunk-Kender, © Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, courtesy Yves Klein Archives.

Klein’s performances didn’t always include himself. In his unrealized plans for “Capture du vide,” the residents of a particular city would be asked to return home at a designated hour, leaving the outside world devoid of people and their sounds. At the opening of the Galerie international d’art contemporain, Klein organized nine musicians to perform his Symphonie-Monoton-Silence. The musicians were instructed to play one note for twenty minutes. Klein dressed to the nines in a tuxedo and a white bowtie and was a step removed from the performance. Though he was the artist, he wasn’t creating the art or the music. Instead, he directed the musicians as well as a group of models to make his paintings. The models were nude women who slathered paint on their bodies and then pressed themselves up against sheets of paper, their body marks becoming Klein’s paintings.

Yves Klein, “People Begin to Fly (ANT 96),” 1961. The Menil Collection, Houston. © 2010 (ARS), NY/ADAGP, Paris. Image courtesy The Menil Collection, Houston.

Klein is often quoted as having said that his paintings were the “ashes” of his art. This could, of course, refer to his use of fire as a medium with which to paint, but also to the less-than-necessary (to him) physical evidence that his paintings represented. Many times he was more interested in the performance more than the material outcome. For his Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility, Klein sold immaterial zones for gold. The artist would write a receipt for the transaction, which would then be burned and the gold thrown into the river Seine.

When Klein was 19 in 1947, he sat on the beach with two friends and made his first work of art — he signed the sky. This was just the beginning to Klein’s short but rich artistic career as creator of performances and ideas. The Hirshhorn exhibit begins and ends with the classic photograph of Klein jumping off a building called Obsession with Levitation (Leap into the Void) from 1960, showing Klein’s desire to leave the realm of the static. Calling himself the “painter of space,” Klein was deeply interested in the world around him and incorporating it into his art. That he had this act photographed (and there is a big debate as to the validity of his leap photographs) and the picture circulated proves that for him, acting out was more than just part of his persona as an artist; it was a large part of his art-making practice. Additionally, Houston’s Menil Collection is showing a concurrent exhibit, which I unfortunately haven’t been able to see, called Leaps into the Void: Documents of Nouveau Realist Performance. It takes Klein’s leap photographs as a point of departure and focuses on the group Klein was part of, The New Realists, and their interest in performance work.

This past year, New York has been lucky with its exposure to performance art and it is a shame that neither this Klein retrospective nor the Menil show will travel here to ground some of the more contemporary works we have seen. Following a strong Performa season, William Kentridge staged I am not here, the Horse is not Mine at the Museum of Modern Art. In it, Kentridge acted alongside a video simulacra of himself on an empty stage save for a metal studio ladder. The Modern also housed an extensive retrospective on Marina Abromovic, which included a live performance by the venerable performance artist pioneer herself. Over at the Guggenheim, Tino Seghal from Germany took over most of the museum for a six-week exhibition. Seghal hired what he calls interpreters (actors) to walk along up the museum’s spiral, telling visitors rehearsed anecdotes and asking pointed questions all with the overlying question of “What is progress?” Should you not have chosen to take one of Seghal’s interpreters up on their offer to accompany you on your walk up the spiral ramp, your visit would have been decidedly less rich than if you had said yes. The New Museum brought Pawel Althamer’s Schedule of the Crucifix, and then Kate Gilmore’s Walk the Walk exposed office-cubicle workers to a taste of performance art in midtown’s Bryant Park. We also shouldn’t forget Gelitin’s collaborative art performance, Blind Sculpture at Greene Naftali Gallery in Chelsea.

These artists were likely all influenced by Klein—particularly those who cross media, as he did. After this rich lineup of contemporary performance art in New York, it would have been beneficial to see the work of an artist who led the way.