Tim Hawkinson, Apples and Bananas, 2010 Apple cores, banana peels, grape skin, twist ties, bread tabs, orange peel and bronze, 9 1/2 x 4 x 3 1/2 inches. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

From intimate sculptures to mammoth collages, Tim Hawkinson (Season 2) gracefully creates tension between the playful and the profound. His current exhibition at Blum & Poe continues longstanding threads while embarking on new investigations, exploring the human body, time, death, spirituality, and the cyclical nature of existence. He recently walked me through his exhibition, shedding light on the process for each new piece.

Lily Simonson: How does place influence your work? Los Angeles?

Tim Hawkinson: It’s not so much Los Angeles as more specifically our home and our living circumstances. Having banana peels lying around – Patty [Wickman, spouse] is into composting. I think it could really be anywhere. Any place would have a definite impact on my work, it’s just not quite as broad as Los Angeles.

LS: Did your work change when you moved from downtown Los Angeles to Altadena?

TH: Superficially, just in terms of what materials were available, what presented itself out in the alley. [Using found materials] is just one of the things that goes into the mix. So just staying open to these things that present themselves. They can be found objects or found ideas, or found images.

LS: With Apples and Bananas the materials become the title, too. Is it important that the viewer knows the materials used?

TH: Well for something like this, which at first seems so horrific, to know that it’s really just made of apples and bananas kind of softens the morbidity, for me anyway. So maybe I took that into consideration when I was titling it…. For certain pieces, I have a title in mind earlier on. But for something like this it just suggested itself. There’s also a song that my daughter Clare learned early on. “I like to eat apples and bananas” and you change vowel sounds each time you sing it.

LS: You mentioned in your Art:21 segment that certain ideas stem from childhood fascinations.

TH: Certain ideas, yes. Ideas revolving around certain immature fascinations–like mummy hands–would fall into that category. That piece definitely resonates with my childhood, and wanting to create something that pulls me in but repels me at the same time

LS: What’s the significance of the jewelry in this piece?

TH: It might identify it as royalty or maybe a priest or priestess. It’s what you would expect to see if you came across something like this in the British Museum. I wanted to make the jewelry in the same vocabulary as the hand. The [band of the ring] is a twist tie and for the scarab, I laminated plastic tabs from a loaf of bread. If you look underneath there’s an expiration date – February 2.

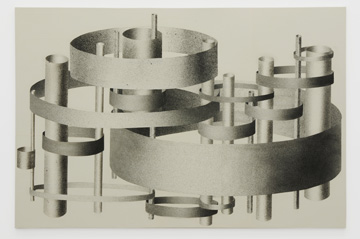

Tim Hawkinson, Cylinder Composition, 2010, Ink on paper mounted on panel, 96 x 144 inches. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

LS: Tubes and cylinders are repeated throughout the show.

TH: I’ve been thinking about the body as a blastula. It’s a simple organism that eats and shits…It looks like just a short tube thing, a mini-processing plant taking food in and waste out. So the tubes and cylinders might relate to that model, and also the idea of containment, as well as the cyclical.

[Cylinder Composition] is kind of a crude airbrush painting. I used a Hudson sprayer meant for spraying weeds. It’s a really course dispersion. And then I also made a rotary/crank sprayer using a toilet brush. It’s collaged… My thinking about this piece had to do with the relationships between the cylinders and how they are suspended within each other and form linkages. They’re also kind of like belts in a motor.

LS: I don’t know if you think about work in art historical terms, but I always saw through-lines from dada. But this one relates visually to Futurism.

TH: Yes, I saw a relationship to futurism. I was thinking Boccioni, the futurist, doing Morandi…I like [Futurism’s] innocence and naiveté in thinking that the future is the ultimate answer. It’s very hopeful but sort of dead-ended.

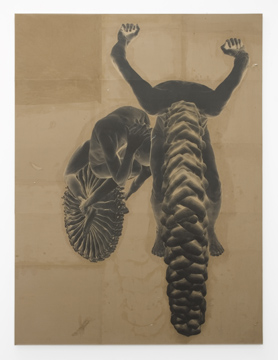

Tim Hawkinson, Bike, 2010 Collaged inkjet prints on mounted on panel, 120 x 90 inches. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

LS: Another motif in your recent work is bicycles. Is there something about bicycles that is significant to you?

TH: I think the bike image is kind of an extension of the body. I’m drawn to these mechanisms that are completely visible. Where you can see how all the parts work together. Ships, bikes, motorcycles. I think I was drawn into this through the pattern of the tire tread, and using images of my fingers – which have their own kind of tread – to create that pattern. The interlocking fingers become like praying hands.

LS: Do spirituality and religion come into your work?

TH: I don’t consciously direct it. I think I’m a spiritual person and I find spiritual interpretations and see connections through that perspective. But I don’t try and suggest any sort of interpretation based on my perspective.

Tim Hawkinson, Orrery, 2010, Plastic bottles, shopping bags, inkjet prints, twine, string, wire, foam, springs, tape, lead and steel 93 x 96 x 96 inches. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

LS: I could not figure out if the pattern on the figure’s dress is really moving, or if it’s an illusion.

TH: I found this pattern on the internet. Kitaoka Akiyoshi is a Japanese psychologist who has created a number of these optically moving patterns. It’s called “Rotating Snakes.” I printed it out in different sizes. It’s an optical illusion, there’s a sort of interference that causes your eye to move the discs around, I think it involves the interaction of the yellow, green and blue.

The title comes from the science classroom model of the solar system where the planets and moons are operated by a system of gears and belts and they all rotate around the sun. So here, the figure is a sort of mother/creator figure working at her spinning wheel … The cosmos, and all those other references going back to this domestic creator.

LS: When did you first become interested in creating work involving motors or creating some sort of system?

TH: One of the first motorized pieces was a really crude music box. I wanted this way of creating music. I didn’t want to use a computer or recording, I wanted an authentic acoustical production of sound. The machine creating it was hesitant and faltering and I liked the idea that it could be perceived as somebody actually plunking out a tune in real time. I like how the machine approaches our own imperfections.

LS: Do you think about imbuing the work with consciousness?

TH: No it’s more of a receptor for our own consciousness. A sounding board for whatever consciousness we bring to it. That’s where the life comes from, I think.

Tim Hawkinson, Wing Back, 2010, Chrome coat, paper, urethane foam and bondo Two parts; 43 x 28 x 48 inches overall photo credit: Josh White. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

LS: This piece, Wing Back, also feels different.

TH: It’s a more personal piece than most of the other work. I wouldn’t necessarily expect the viewer to make the same associations I do with it, but basically, it’s a calm domestic setting that contains a certain amount violence–suppressed violence. For me it looks like shattered glass. The image of the wingback chair is suggestive of a guardian angel, or maybe an angel of death.

LS: Do you think that death comes up in your work often?

TH: More so it seems in this show. There seems to be a lot of mortality.

LS: Visually, Wing Back relates strongly to the Snails piece. What was your process for Snails?

TH: I’ve made a few drawings like this where it starts as a basic grid which becomes more and more complex. I start with a large fairly even grid composed of large dots, and use that as anchoring points for a smaller tighter grid, which then becomes the basic structure of a still denser grid, and so forth. Since I’m doing it all without measuring or using a straight edge, this kind of turbulence surfaces. So as the grid becomes denser and more filled in, the structure created becomes more and more fluid. The dotted lines start to look like a snail’s path.

Tim Hawkinson, Track, 2009, Aluminum tape, Faom, PVC, and Wire. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

This piece [Track] is a continuous spiral that oscillates between two points. It’s a really complicated figure 8 that continuously loops back in on itself. I was looking at images of the Lorenz attractor, which looks kind of like a bicycle tire with the treads spinning off the tire and ripping apart. Tread seems to be a recurring theme, like the snail track, traction, fingerprints. The rug in Orrery is made up of twelve rings which are photos of bicycle tire tracks in sand. I think it’s an interest in how one thing grips another. How we touch and grasp.

LS: Does your daughter, Clare, have a favorite piece in the show?

TH: She says it’s the candle. She likes to go in there and shut the door.

Tim Hawkinson, Candle, 2010, Foam, wood, emergency blanket, mixed media 94 x 94 inches, photo credit: Josh White. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

LS: The doorway seems like its kind of child-sized…

TH: I just wanted to create a warm and cozy work environment for whoever has to go in and repair it. The interior is lined with gold emergency blankets. When I was working on it, at one point, I was getting a cold and I noticed that I felt so much better when I was inside, surrounded by this warm gold incandescent light. It feels like the embodiment of a candle. And it’s a tube. As it burns out it forms a cylinder. Another blastula.