Last month while I was working on projects for the grand opening of 100 Acres, one of the most important international conservation symposiums took place in Amsterdam. Contemporary Art: Who Cares? Research and Practices in Contemporary Art Conservation was organized by the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage (ICN), Foundation for the Conservation of Contemporary Art in the Netherlands (SBMK), and the University of Amsterdam (UvA). The symposium was an activity of the International Network for the Conservation of Contemporary Art (INCCA).

Karen te Brake-Baldock

As a way to find out what I missed, I’ve invited Karen te Brake-Baldock, a researcher at ICN and the INCCA Central Coordinator here for a discussion. Karen obtained a BA in Arts & Media Management followed by an MA in European Arts Management in 2002 from the Utrecht School of the Arts. In 2004, she started working at the ICN as assistant manager for the ground-breaking European Union project Inside Installations. She has been INCCA’s Central Coordinator since 2005.

Richard McCoy: I understand that the attendance for Contemporary Art: Who Cares? (CA: WC?) included museum directors, private collectors, conservators, artists, artists’ assistants, art historians, collection managers, conservation scientists, technicians and students for a total of over 550 professionals from 32 countries. Was this big of an attendance anticipated, or was it a bit of a surprise?

Opening Day of CA: WC? at the Royal Tropical Institute

Karen te Brake-Baldock: The symposium Program Committee (Paulien ‘t Hoen, Tatja Scholte, Vivian van Saaze, Lydia Beerkens, and I) expected a good turn out, at least as many people as we had 13 years ago for the symposium Modern Art: Who Cares?. The event was held at the Royal Tropical Institute, which has an auditorium that seats 435 people. We thought [that] with a bit of PR effort, we should be able to fill it.

However, 3 months before the event, all of the tickets were sold out and we had a waiting list of over 100 people. Something needed to be done! It was too late to change the event location so we arranged for a live television feed from the main auditorium to be set up in an adjacent room to follow the plenary lectures. In the end, around 580 people were present at one time or other. So yes, it was indeed a bit of a surprise!

RM: One of the things I found most intriguing about the symposium is that the plenary sessions seemed to focus less on conservation treatments, and more on theoretical issues related to collections development and management, and notions of public access. Do you think this approach was well-received?

KtBB: The three-day program was based upon three phases in the conservation continuum and the notion that different aspects of conservation take place during the “lifespan” of an artwork. The point of departure is the concept that contemporary conservation issues cannot be dealt with without considering the relationship to artistic and museum practices. (The term “conservation” is being used here in a broad sense.)

I think the the symposium program successfully illustrated the premise that conservation is an intrinsic aspect through the various stages in the life of an artwork. There are many factors influencing the way museum professionals work today, including the way artists work and the kind of work they produce, changes in the role museums play in society, and how the public obtains and shares information and knowledge about artworks. Conservators and other museum professionals are redefining themselves as these changes occur. Promoting discussion and reflection from different perspectives is important if we are to keep up with these changes.

To answer your question directly: for many attendees this approach was well received. Trying to please such a large group of individuals from different backgrounds is quite a challenge. A number of conservators said, for example, that they would have preferred less lectures and more hands-on (practical) workshops. One art historian mentioned that she thought the discussions were not as thorough and deep and she was used to. On the other hand there were some conservators that were very pleased with the openness of the discussions. I guess it is all up to where you’re coming from and what expectations you had.

RM: As an art conservator that works at an encyclopedic museum, I recognize the differences between the approaches taken at museum’s like mine and that of museums that solely specialize in contemporary art. With this in mind, I wonder if there were many discussions around how art museums are changing in the 21st century.

KtBB: The subject was certainly dealt with in the first day by keynote speaker Charles Esche, director of the Van Abbemuseum. In his talk, The Politics of Collecting within the Possible Museum, he discussed how in order to make decisions on what you collect as a museum, you firstly need to ask the questions like: “What should a museum look like today?”, “How does it behave towards the art of the present moment?”, and “How does it respect and animate its past?”

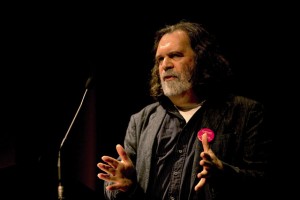

Charles Esche speaking at CA: WC?

The innovative force of the museum is not only—or not so much—in the expansion of collections with new acquisitions, but in the examination of the narrative of the collection, and the communication of this with the public. The museum as an archive of cultural memory is capable of constantly and actively interacting with present-day visitors. Today’s museums are challenged with finding engaging and interesting ways to do this.

When dealing with the subject of the third day of the event, Access, presentation and the public, it is impossible not to reflect on how museums are changing in the 21st century. For example, the Stedelijk Museum, which has been closed for many years for renovation, has had to invent new ways of presenting their collection to the public.

RM: If I would have been able to go to just one day of the symposium, I probably would have gone to that third day on Access, presentation and the public. Conservation events don’t often address this topic directly, or devote much time to it. Can you tell me a bit about how that day went?

KtBB: This was my personal favorite too. The three speakers were very strong and I enjoyed their talks very much. The response from the audience was good but there were not many questions; I am not sure if this is a good or bad sign. I know many were inspired by museologist Peter van Mensch’s talk, A Work of Art in a Museum is a Work of Art in a Museum. One of the questions he posed was: “Who is defining the significance of an artwork in a museum context?”

Peter van Mensch

He also investigated how museums relate to social inclusion, access, and participation with the public. In his view, museum professionals have too little of an awareness of an integral approach of engaging the public (combing a cross-disciplinary museological approach with artists and audience voices). The consequence of this is an alienation from the public’s responsibilities towards our shared museum heritage in all sectors, and of course in contemporary art!

The topic of Access, presentation and the public is indeed a new subject to be dealt with in conservation symposia. As mentioned earlier, conservation and the role of the conservator is an integral part of all of the phases in the lifespan of an artwork; including the essential phase of presentation to the public. In the case of complex installations, it is often the conservator (through documentation and artist interviews) that has the most knowledge about an artwork and understands how it should be presented (and what is technically possible). In this sense, the conservator has an essential role in the presentation of the work.

RM: As you mentioned earlier, this symposium is a follow up to the 1997 symposium, Modern Art: Who Cares?, which resulted in a seminal publication with the same name. To put it bluntly: in what ways do you think the field has changed since 1997?

KtBB: Modern Art: Who Cares? (MA: WC?) was, in the eyes of many, a real starting point for a new way of thinking about the conservation of modern and contemporary art. The four main changes that have occurred since then were summed up nicely by Tatja Scholte during the closing session:

Artist participation in conservation: Thirteen years ago, there was a backlog in material-technical information on contemporary art. In particular, information on the artist’s choices for material, technique, or medium was lacking.

In addition, information on the artist’s choices in relation to artistic intent was not often addressed by art critiques or in other writings. A general belief in the “artist’s voice” gave an impetus for many conservators to actively engage with artists and assistants in collecting a new kind of information and to start a dialogue on conservation. Today, interviewing artists or collaborating in other ways is common practice and in many countries projects have been running on this subject since then.

Platform for information and knowledge exchange: In 1997, there was no platform for sharing information about the conservation of modern and contemporary art. In 1999, a group of 23 European professionals established the INCCA. Now the network is truly international and has grown to include around 400 members in over 40 countries. The Internet provides useful communication tools, but the development of the profession can only be achieved through the active participation and sharing of information.

Installation art: Inside Installations (2004-2007) was an important project in Europe, but at the same time, it was just one of a number of projects on this subject running in Europe, USA, and Canada. Driven by the art production and museum acquisition policies, installation art, and the problems with the conservation of time-based media have, in more recent years, been at the top of the agenda of many museums and conservation studios. Many cross links between such initiatives can be made and somehow all of them are part of this worldwide knowledge network in which complex installation works of art are situated.

Training for conservators: At the time of MA: WC?, there were no specialized educational programs for the conservation of modern and contemporary art. These days, we have all kind of programs all over the world. Only recently, an INCCA education group has been established to enable educators to work together to in creating consistency and improved quality in education. The group’s main aim is to facilitate a dialogue between educators on contemporary art conservation and to create a platform for information exchange via our website. In addition, during the symposium, a new network, affiliated to INCCA, has been established, for PhD and postdoc researchers.

CA: WC? reflects the development of all of the issues that were raised during MA: WC? The depth of discussion was more profound, and much more open, based on the growth in maturity of the profession. The symposium also illustrates the importance of the network we’ve built. Not only was the program built in collaboration, the knowledge shared was developed in collaboration: people working together crossing geographical as well as professional borders.

RM: I know that you’re the project manager for the European Union project Practices, Research, Access, Collaboration, Teaching In Conservation of contemporary art (PRACTICs). With 31 leading European museums collaborating on this project, the scope must be quite broad. Will you talk about the project and how the outcomes are shaping up?

KtBB: I would say PRACTICs is more of a program than an project. It has a number of activities which will result in a symposium, book, enlargement of the INCCA network (geographically and thematically), and research into the topic we call: Access to Contemporary Art Conservation (Access2CA).

After the Inside Installations project came to an end in 2007, the partners felt that, although great research was done and a fantastic resource was created, the results could be disseminated in a different and perhaps more targeted way. This wish primarily resulted in CA: WC? Most of the parallel sessions and a number of the lectures were given by participants from the Inside Installations project and it was thus an opportunity to share what was learned.

Another way of bringing the results of Inside Installations further was to make a book. Inside Installations: Theory and Practice in the Care of Complex Artworks is currently in production and will be published in March 2011. This book will contain 20 chapters in four parts and deal with specific cases where conservation “treatment” was carried out, and issues such as the role of participants in the process and chapters reflecting on the kinds of decisions that are made to in order for installations to be presented (such as computer emulation).

The INCCA network will be expanding during PRACTICs. A new regional group, INCCA Central and Eastern Europe, has already been created, and it is planning its activities for the coming years in the region.

The Access2CA sub-project within PRACTICs deals with a topic that has not often been dealt with in conservation projects. It is generally known that the public is interested in stories of the making of art. There are many examples of well-liked videos about “the artist at work.” The Inside Installations exhibition in the Kröller-Müller Museum in 2006-07 was very successful; in the Netherlands national press, it was listed as one of the year’s top five exhibitions.

Access2CA will establish a relationship with diverse public target groups in matters of conservation and presentation and will guide museum visitors through interesting questions of conservation and presentation while increasing public appreciation of contemporary art. Of course, all of the results of PRACTICs will be disseminated via the INCCA web page, so stay tuned.

Pingback: CA:WC? in the media « Akina Art Projects

Pingback: Interview with Karen te Brake-Baldock about Contemporary Art: Who Cares? symposium | Collectiewijzer

Pingback: No Preservatives | A Fresh Path at the Met: A Discussion with Kendra E. Roth | Art21 Blog