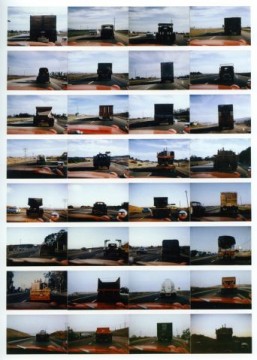

John Baldessari,"The backs of all the trucks passed while driving from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, California, Sunday 20, January 1963," photography, 1963. Via a-n.

Upon entering Pure Beauty at LACMA, I overheard a fellow museum-goer tell his companion, “That’s cool — it looks like a lot of my iPhone pictures.” The viewer was responding to The Backs of All the Trucks Passed While Driving from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, California, Sunday, 20 January 1963 — the first of more than 150 works in John Baldessari’s retrospective. Navigating through the rest of the exhibit, the viewer’s words echoed in my head, slowly illuminating the underlying threads of Baldessari’s fifty-year career.

In his Art:21 interview documented in the Season 5 companion book, John Baldessari tells us: “I was getting tired of hearing the complaint, ‘My kid could do this’… And I wondered what would happen if you gave people what they wanted, something they always look at.” While the implications of the viewer’s response to The Backs of Trucks were similar to the typical complaints leveled against conceptual art (as cited by Baldessari), the tone of his remark seemed altogether different. He appeared to be pleased and excited by the idea that, he — or anyone with a simple camera — might produce similar images. By giving people “something that they always look at,” Baldessari seems to sidestep the problems faced by most conceptual artists. He consistently avoids alienating viewers, no matter how facile his approach may seem.

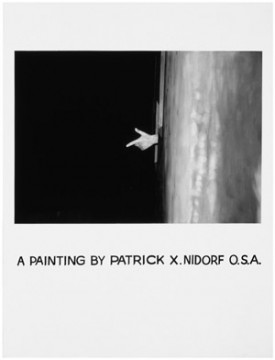

John Baldessari, "Commissioned Painting: A Painting by Patrick X. Nidorf O.S.A," 1969. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 59.25 x 45.5 inches. Courtesy John Baldessari/Via X-TRA.

Rather than drawing solely from traditional curatorial commentary, the wall labels of Pure Beauty are peppered with quotations from Baldessari. For the 1969 Commisioned Painting series, Baldessari explains that he wanted encourage the audience “to practice connoisseurship.” By repeating the element of the pointed finger, Baldessari empowers the viewer, allowing he or she to compare the different approaches to painting practiced by each commissioned artist. By drawing the viewer into the work in this way, Baldessari always firmly positions his audience as “in on” the joke, rather than as the butt of it.

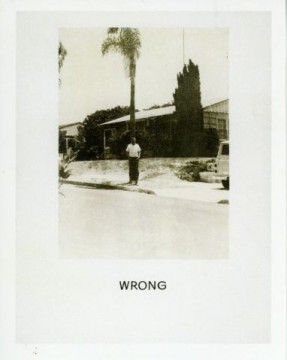

Though consistently humorous, Baldessari never enters the territory of smugness. While the work typically sets up humorous scenarios, there is often no clear, singular punchline. From 1969’s Ghetto Boundary Project to 2004’s Five Yellow Divisions: With Persons (Black and White), Baldessari manages to provoke nuanced lines of questioning through simple juxtapositions of words, images, and symbols. While works such as Wrong address the absurdity of aesthetic didacticism, he refrains from implying any clear conclusions about the purpose of visual standards. Even the most comical juxtapositions in the work transcend the realm of the one-liner, hovering instead within the provocative territory of the riddle. Indeed, the driving force of Baldessari’s process is not comedy or irony, but a sincere interest in dissecting and understanding the world. In his Art:21 interview, Baldessari explains, “I don’t see what I do so much as humor as I see it as an attitude or how I look at the world… it’s a way to make sense. If I were trying to be funny it would be a different kind of work.”

John Baldessari, "Wrong," photoemulsion and acrylic on canvas, 1966-68. Via a-n.

While Pure Beauty originated at the Tate Modern and will arrive at the Met in October, Baldessari created a special work to celebrate the exhibition’s opening on his home turf. The interactive piece, entitled In Still Life 2001-2010, allows the viewer to create his or her own version of Abraham van Beyeren’s Banquet Still Life by digitally rearranging more than three dozen elements within the 17th-century painting held within LACMA’s permanent collection. Available as an application for the iPad and iPhone or else as a good old fashioned website, the piece actually began, as the title suggests, in 2001 when Baldessari created an on-site version, in which LACMA visitors could arrange elements of the same still life painting and project the image onto the gallery wall next to the original work. Whereas users of the earlier iteration could print and email their remixed still life images, the participants can now share their compositions on Flickr and Facebook.

The author's version of "In Still Life 2001-2010." Courtesy: ForYourArt/John Baldessari.

At first glance, Baldessari’s foray into net art might seem abrupt. Yet within the context of the retrospective exhibition, one can view it as part of his longstanding interest in democratizing the process of relating to art, and leveling the artist/viewer/artwork playing field. Moreover, given works such as Choosing (A Game for Two Players): Carrots, In Still Life 2001-2010 feels like a natural continuation of Baldessari’s leitmotif of play, selection, and decision-making as a metaphor for the artistic process and for the way we live our lives. While Baldessari says that he chose a “generic” still life, he believes that there is a hierarchy among the elements within the painting: “The lobster is the most important object in the painting. I’m just anticipating everyone trying to make the lobster dance and do back flips.” But can the iPhone app run simultaneously with the camera feature? I would like to make the lobster dance around the photos I take of the back’s trucks.