Shaun Richards, "Lost Highway," 2010. Mixed media, oil, and silver leaf on canvas, 96x132 inches. Courtesy the artist.

What does it mean to live and work as an artist in the South? It would be foolhardy to suggest there is a single, unified answer to this question. I think prevailing sentiments and themes emerge, however, through even a cursory glance at a scene like the one here in Raleigh and the Triangle (for strangers to the area, the “Triangle” is a piedmont region in North Carolina, loosely demarcated by neighboring Raleigh, Chapel Hill, and Durham). I grew up here and continue to practice here, and I maintain that there are compelling reasons to consider the changing landscape in this New South as the catalyst for some important American art.

Raleigh is perhaps not your prototypical Southern town; Wake County — in which the city is situated — has surged this decade to become the most populous county in the state, according to recently released data. And the cultural scene is, in many ways, thriving. (It’s finally feeling, at least, like our institutional and informal structures are catching up with the last two decades’ influx of people and energy.) This year alone we’ve seen the opening of the NCMA’s world-class West Building, designed by Thomas Phifer, and the long-awaited breaking of ground for CAM, Raleigh’s Contemporary Art Museum. The public presence of art here has never been stronger, in terms of both state and municipally-supported projects and private initiatives like the creative conference SPARKcon, which rules downtown Raleigh in early September. (Actually, this fall, SPARKcon will share the city’s stage with the Independent Weekly’s massive Hopscotch Music Festival, the likes of which this town has never seen.)

In the broader Triangle, exhibitions and programming at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University have upped the ante in regards to the presence of internationally significant contemporary work and critical discourse in the area. Aaron Greenwald has revamped the Duke Performances series in amazing ways. Full Frame and the American Dance Festival happen here. In Chapel Hill, there’s the University, which boasts the Ackland Art Museum, a top Studio Art program and another great Performing Arts series. Neighboring Carrboro is home to the Cat’s Cradle — and the continued importance of that nationally renowned club to the cultural scene here, in my opinion, cannot be overstated.

This is fertile ground for artists and practitioners. (Not to mention, rent is cheap.) But, insofar as the critical radar of contemporary art writ large only tends to register New York, L.A., and a few select places in between, it often feels as though making the choice to practice here is to accept a place outside the broader dialogue. Still, practicing here is a choice many of us happily make. Over the course of the next week, I’ll be taking a closer look at the often shrewd emotional, strategic, geographic, computational, and occasionally mystic logic behind the choice to practice in the South, particularly this New South of upper-mid North Carolina. I’ve asked a carefully crafted (yet ultimately somewhat subjective) selection of artists practicing in the Triangle to respond to the prompt: why here?

I began these informal conversations by speaking with Tracy Gail Spencer and Shaun Richards. For both artists, as it happens, the answer to the question involves the logic of return. Spencer grew up in Greensboro; Richards in the Tidewater region of Virginia. Both pursued undergraduate degrees in art in North Carolina and made their way to New York after college. And ultimately, both uncovered reasons to bring their practices back to the South.

HL Roaming Gallery 5, 2007. Raleigh, NC. Courtesy Tracy Gail Spencer.

The current cultural gestalt in Raleigh owes a great deal to the urban pioneering Tracy Spencer spearheaded downtown before leaving North Carolina to pursue an MFA at Pratt in 2008. While she was an undergraduate at the College of Design at North Carolina State University, Spencer founded the Fish Market, a downtown gallery whose ongoing mission is to showcase the work of students at COD. After graduating in 2004, she organized a series of roaming galleries in provisional warehouse spaces in parts of the city then relatively devoid of economic and social activity. Artists across the country out of necessity often do the work of pushing into areas that later become cultural hotspots — this has certainly been the case in Raleigh, as the locations of Spencer’s roaming galleries presaged the revitalization of parts of the downtown core.

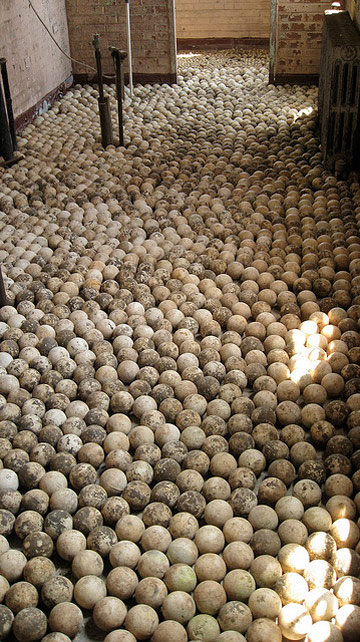

Flocculation balls at The Bain Project, 2009. Courtesy Brooke Chornyak.

In 2008, Spencer began work on what would be her most ambitious curatorial project at the city’s abandoned water treatment plant south of downtown. The E.B. Bain Waterworks, a 1939 Art Deco marvel, had been shuttered since the eighties and virtually undisturbed when Spencer and painter Daniel Kelly began working in concert to assemble a site-specific installation. They culled twelve artists from over a hundred applicants to form a well-rounded team that would ultimately built on the mystique and beauty of the space and its entropic guise. Open only for two weekends in May 2009, The Bain Project captured the imagination of thousands and brought attention to a part of the city virtually forgotten by its denizens.

The archeological tendencies evident in Spencer’s curatorial projects also emerge in her own work. “I stand on a compact landfill of family history, legend, and objects,” she told me. A recent piece, Bloom, hung on the wall of the fifth-floor residence where we met to chat. Saturated hues owned by synthetic ornamental flowers and antique matchbox cars delicately attached to a stretched canvas support vibrate against a pale chamomile gradient that shifts from linen to lemon yellow. Spencer is coming to see her combines as curated selections of objects suggesting both the promise and danger of excavation. She describes her ongoing efforts to dig into her own working-class family roots, obscured by time and tacit acceptance. It’s an example of the kind of situated work difficult to conduct at a distance.

In 2008, Spencer moved to New York City and enrolled at Pratt as the Bain Project was in full swing. She spent time as an intern at the Sculpture Center in Long Island City, collecting and documenting work for the Center’s annual fundraiser, learning about the museum system firsthand. She also worked as an assistant at Tracy Williams, LLC, preparing their collection for Art Basel 09, managing the gallery during the fair, and writing press releases. But her own practice suffered. She made the tough choice to return to North Carolina and transfer into the MFA program at UNC-Chapel Hill.

During our meeting, the ways in which Spencer spoke of arriving at the decision to return south echoed what I’d heard in my earlier conversation with Raleigh-based painter Shaun Richards. Richards’s dalliance with New York began in 2003 when he enrolled at SUNY-Empire State as a non-matriculated graduate student — a situation which afforded him a studio in Manhattan and weekly visits and crits with established practitioners. He found himself working at a commercial art company, trying to maintain his practice in what often seemed like a “pressure cooker” fraught with “rampant careerism.” Scraping by was difficult. Soon, he was fantasizing about the South, conjuring images of pastoral Americana from his Brooklyn apartment. Seeking to return to a full-time art practice and a higher quality of life, in 2006, Richards arrived in Raleigh.

Both Richards’s and Spencer’s reasons for returning lean heavily on the appreciable freedom one is granted here to make aesthetic decisions unencumbered by the weight of the museum-gallery-magazine critical apparatus. Of course, an acute consciousness of the scene can dog an artist wherever she chooses to practice, but the power dynamic in a cultural center of gravity like New York might more frequently and more fatally shift from exhilarating to exhausting. Here in Raleigh, Richards says, he can give himself as much time as he needs to incubate an idea, developing and collecting the formal components he layers into his epic collages, over which he paints images and graphics that speak to the (southern) American situation. Work he developed since his return recently led him to the Bemis Center in Omaha for a three-month residency, during which he produced a series of paintings representing the economic crisis as a series of allegorical car crashes. His canny deployment of typographic treatments from movie posters and his incorporation of materials found at junk and thrift shops are integrated more fully and strongly than ever before. Richards describes his progress since returning: “The work has evolved… (to reflect) an interest in social dynamics, role modeling, and how the media plays into that. I’d still say it’s southern, as that’s part of who I am. But rather than romancing that from afar, here I’m able to affect as well as be effected.”

Despite the literal and critical distance between this place and Northeastern hubs of culture, artists like Spencer and Richards actively choose to stay put and root their practices in the South. The Triangle is home to a growing, active, supportive creative community, and that certainly distinguishes it from some other southern locales. It is still, however, a long way off from the supposed center of contemporary art discourse. There certainly are trade-offs involved in choosing to be here. I hope by representing some of the voices of artists working and practicing here over the course of the next week that I may shine a little light on why the decision to stay is an eminently reasonable one for people who care no less about art and believe no less in its power to change our ways of seeing and being.

I welcome readers (no matter where from) to reflect and contribute their own stories and responses to the prompt, why here? in the comments.