Kip[p] Stagg, nineteen years old and a Columbia undergraduate, was walking in New York one night in 1965 when he heard a man’s voice shouting names at him from somewhere across the street: Igor Stravinsky, Maria Callas, Mick Jagger (there was a fourth too, but I’ve forgotten it). The personality behind each name had made a seminal appearance in the city that year—The Rolling Stones played Carnegie Hall on their first-ever American tour—and Stagg knew this. The shouting man, who turned out to be the same Chuck Wein who purportedly got Edie Sedgwick stoned to sabotage Warhol’s Kitchen, knew this too. But to peg Stagg so well, he must have either had stand-out hustling savvy or eerie good luck.

Intrigued, Stagg joined Wein and talked as they walked toward Wein’s destination, which turned out to be Warhol’s Factory. Wein invited Stagg up and they rode the freight elevator to the landing, where they met a topless Brigid Berlin. “It was not a pretty sight,” said Stagg, who soon found himself trapped behind a running camera. The four-minute Screen Test that resulted played at Hollywood’s Egyptian Theater Sunday, August 8th, two days after Warhol’s 82nd birthday. Stagg saw it for the first time that night, right before telling all of us in the audience his story of nighttime New York, precocious Wein and brazen Berlin.

Sunday’s screening, hosted by The Los Angeles Filmforum, included nine other Screen Tests from Warhol’s Reel #4. In each, the unmoving camera meets its subject head on. The result is silently slow and pensive. “You would see the person fighting with his image—trying to protect it,” said Mary Woronov, a self-described “rebel artist” who belonged to the Factory and wrote about it in a memoir called Swimming Underground. Such fighting happens in most of the tests that ran Sunday, but clean-shaven Dennis Hopper of 1964, who appears on the reel twice, seems uncannily comfortable with himself.

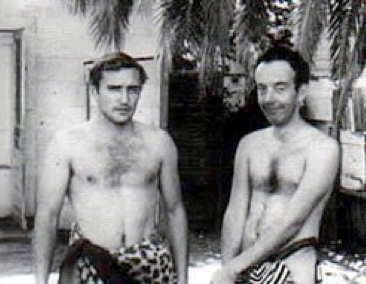

The screening coincided with MoCA’s Dennis Hopper Double Standard, and Hopper also made a brief appearance in the evening’s longer film, Tarzan and Jane Regained . . . Sort of, a peripatetic, painfully drawn-out farce in which the elfish and flimsy Taylor Mead cavorts in a loin cloth at beaches, hotel pools and other Los Angeles haunts (Warhol made Tarzan on his first trip to L.A.). Hopper plays Mead’s stunt double, dashing up a tree to pick a coconut, and fleetingly comparing his biceps with the less-endowed Mead’s. He looks intermittently awestruck and amused the whole time he’s on camera.

There’s a faux looseness to Tarzan that mirrors the faux looseness of what’s been happening in a segment of Los Angeles’ art scene this summer—characters and locations seem haphazardly intertwined, when, actually, they’re deliberate and specific. Easy Rider screened at Hollywood Forever Cemetery a week before clips from the same film would appear in the just-opened Double Standard. James Franco and Kalup Linzy performed for a maudlin soap episode at MoCA’s Pacific Design Center a week before the inside of the same space would be turned into an equally maudlin but more aggressive habitat for Ryan Trecartin’s visually raucous and linguistically agile Any Ever. The films installed in the galleries at MoCA PDC would then be projected to audiences at Cinefamily, the vintage theater on Fairfax Avenue. And Hopper would reappear at the Egyptian. Though none of these events occurred spontaneously, the fact that they feel as though they could have makes them Warholian.

Critic Stephen Koch described Warhol’s shtick in the 1989 documentary A Mirror for the Sixties:

He was constantly asking people, Do you have any ideas? I don’t have any ideas. It was almost a Buddhistic pose of transparency which used other people and sometime someone . . . would say, yes, I do. And that answer would then be fed into what was a very selective understanding of what he, Warhol, was up to.

Warhol was up to curating people. He wanted a microcosm of sometimes attractive, sometimes eccentric, hungry personalities with obsessive brains, the sort who looked like Dennis Hopper or James Franco, knew what Stravinsky and Mick Jagger had in common, and would follow someone as strange as Chuck Wein home late at night.