We’re accustomed to porticoed Greek temple-style museums, white-walled galleries, conspicuous label texts, a high level of organization, and clearly-defined thematic spaces. For those of us who are city-dwellers, we expect outdoor public art to remain confined to our meticulously landscaped parks. When art projects unexpectedly seep out of these borders — which they increasingly do — the result is often surprising and delightfully engaging, redefining our environment as the ultimate museum, and promoting creative efforts as approachable and fun exercises to be found around any corner.

Here I consider the natural world as the physical setting for art. “Natural world” need not necessarily mean, however, the untamed wild, but any site upon which humans build the basis of their lives. Cities are prime hubs for inventive initiatives: whether it be in the form of waterfalls, icebergs, or elephants on parade, art has the unique magical power to transform our mundane man-made environment into that of an urban jungle.

Some open-air art exhibitions can reflect social concerns and encourage change, as did the many eco-focused projects — from Angela Palmer’s Ghost Forest, to Mark Coreth’s Ice Bear, to Millennium ART’s CO2 Cubes — planned around last winter’s UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen. The event inspired a virtual explosion of art, practically converting the country into a cultural institution capable of city-wide curation, and featuring an impressive array of work both official (the RETHINK: Contemporary Art and Climate Change exhibition at the National Gallery of Denmark) and unofficial (Banksy’s I Don’t Believe in Global Warming graffiti). Other projects are less morality-based, and involve a more light-hearted, whimsical approach; notable examples include tracking designer chair envy (the Blu Dot Real Good Experiment) and Luke Jerram’s ongoing Play Me, I’m Yours venture in impromptu musical performances.

Olafur Eliasson, “New York City Waterfalls” (2008), Brooklyn Bridge, New York City. Image via Flickr. Photo by Michael Sorgatz.

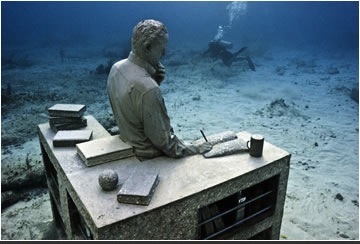

My favorite current art scheme is one that is isolated from the urban landscape and wholly submerged in the natural environment … literally. The Underwater Sculpture Museum off the coast of Isla de Mujeres and Cancun, Mexico, is a product of the contemporary penchant for intermingling ecological concerns, science, and aesthetics. Housed within the protected site of the Cancun National Marine Park, the museum showcases work by sculptor Jason de Caires Taylor. Though situated near marine reefs, the sculptures are designed to lure snorkelers and divers away from the fragile ecosystem. The museum’s three inaugural sculpture groups — The Gardener of Hope, The Archive of Lost Dreams, and Man of Fire — are to be joined by over 400 additional Taylor sculptures by the end of the year, and phase 3 will invite additional artists to install and display their work in the seascape. The very materials of the sculptures echo the overall conservation mission of the museum; indeed, Taylor collaborated with marine biologists to create a pH-neutral concrete composition for his work that actually serves to attract and anchor coral, sustain ecological processes, and replenish biodiversity. The art incorporates ghostly nods to the voices and character of the local population: the life-sized human figures are based on actual members of the community, and The Archive of Lost Dreams contains real bottled messages of fear, loss, hope, and belonging.

Jason de Caires Taylor, “The Archive of Lost Dreams,” Underwater Sculpture Museum, Mexico. Image via the artist’s website.

Though the museum can be toured via glass-bottomed boat, it would be well worth the extra effort and cash to explore it as a snorkeler or diver. The underwater location allows for the rare, total three-dimensional immersion into the artwork itself, as there is no distinction between the sculpture and its environment — they are inseparable. The experience is matchless: the sea manipulates visitor perceptions of size, distance, and color; the act of swimming encourages greater spatial engagement; and the symbiosis between the natural and artificial reef habitats creates an incessant interplay that results in a constantly-evolving environment. Weightless and buoyant, there are no walls to dictate your movement, no distracting sensory stimuli such as beeping security sensors or crying children. The underwater museum affords the visitor with the ultimate exercise in meditation, in experiencing something personal and profound. Surrounded by spectral visages of an entirely flooded human world, floating among wildlife, one can attain a cerebral sense of transcendent mystery.

Jason de Caires Taylor, “Man On Fire,” Underwater Sculpture Museum, Mexico. Image via the artist’s website.

I don’t mean to imply that city green spaces cannot be highly skilled and inventive at presenting wonderful art entwined with nature. New York City’s imaginative High Line, the abandoned railway-cum-elevated park, has an active public art program and employs a full-time curator to organize installations of work by contemporary artists such as Valerie Hegarty, Spencer Finch, and Stephen Vitiello. The High Line has been so wildly successful that officials from cities such as Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, Rotterdam, and Hong Kong are considering similar transformative projects, and the founders of Friends of the High Line recently won the Rockefeller Foundation’s Jane Jacobs Medal awarded to those whose work “creates new ways of seeing and understanding New York City.” Across the country in San Francisco, the site-based art exhibition Presidio Habitats will be on view until May 2011 in the national park, featuring animal habitat proposals commissioned from artists, architects, and designers.

Are there exciting or unusual examples of public art in your area? How do you see these works engage the community? Please share any insights in the comments section below.