Last weekend, I stopped at a red light and rolled forward into the intersection to turn right. I didn’t see the pedestrian who was about to cross, and came frighteningly close to hitting him. His body clenched in what I assumed to be anger before he walked around the back of my car. My windows were open and I was nervous. Certainly, I was at fault; still, I didn’t want a confrontation. But when he came up to the driver’s side, he said, in halting English, “I love you.” Then he walked away.

My summer has been like that: situations that I am convinced will be disastrous are instead uncannily poignant, and everything–my life, my work, the art I see–seems to be converging. Art viewing trips turn into drawn out social encounters; social encounters turn into art.

The work of Emilie Halpern, an artist very much interested in convergences, became especially emblematic of the past few months. She kept appearing in shows around Los Angeles (and also in Houston, New York, and Lisbon, though I didn’t see those), and her work constantly seemed to be questioning what it means to love in quiet, unobtrusive ways. Talking with her seemed like a fitting way to end the season, so I visited her Highland Park studio and she told me the story of her summer, which actually began two years ago.

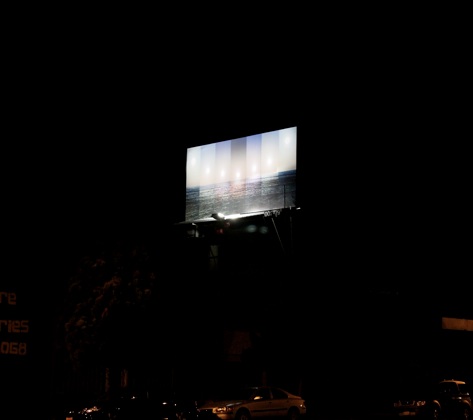

"Cosmos," Emilie Halpern and Eric Zimmerman, 2010. Installation View. Art Palace, Houston, Texas. Courtesy the artist.

Emilie Halpern: After my last solo show at Anna Helwing Gallery [in 2008], everything began to shift, partly because the gallery closed. I did two residency programs, each a year apart, and then—boom—the show at Art Palace Gallery in Houston happened [in May/June 2010].

Catherine Wagley: When I looked at images from Art Palace this morning, I was thinking about how the work broached similar subjects but felt somehow different from your past work.

EH: The shift is subtle. There’s more looseness now and I’m moving at a faster pace, doing less editing. For the last show I did with Anna Helwing Gallery, the work was interconnected, but when I look at it now, I just see how each piece was its own little thesis that I kept refining and refining. When I did these residency programs, I was doing several things at once, not knowing where I was going. Then finally, I looked back and I saw what I had created.

CW: I like the fact that your residencies happen in the spring.

EH: Always the spring. I love going to New England and that’s when things just explode out there. When I was at The MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire in 2009, I arrived at the end of April. I saw the woods without a single leaf and there was still snow melting. Then, within a week, all the leaves came out and everything turned green and it was beautiful. The photographs I did there documented the bare trees in black and white and the lush spring trees that came later.

CW: Were you just responding to your surroundings? You always seem to have some sort of project.

EH: Well, I knew I’d have a black and white darkroom and I thought, okay, I’m going to shoot photographs. I just wanted to enjoy the experience of being a photographer, and I had started to switch to digital so I was getting farther and farther away…

CW: …from the tactile experience of printing?

EH: Yeah, and then I knew I wanted to do ceramics—that’s really new and I think that, more than anything, it’s responsible for the shift in the work. Making clay bowls, that’s a totally different way of being creative than making conceptual art.

CW: I often think about really advanced technology when I look at your work. Partly, this is because you deal with space exploration and scientific minutiae. But you know, even when I think of the love letters and John and Yoko, I think of refinement. So it’s interesting that you would go backward technologically.

EH: Back to the very beginning. Working with the clay suddenly imposed all these organic boundaries. You’re not questioning the material. It just exists. It was a relief for me. My residency at the Vermont Studio Center in 2008 mostly consisted of ceramics and sketchbooks full of notes. A piece for my upcoming solo show at Pepin Moore started there, actually. I read about how a bird that migrates over the U.S. hears both the sound of the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean at the same time. That’s how it navigates. That seemed so impossible to me, though — obviously, it’s not the way we hear. In the piece for the show, the sound of Atlantic Ocean is emanating from one side and the Pacific from the other. When you’re in the center, you can hear both.

CW: Pepin Moore has that great center wall. Are the sounds going to be on either side of it?

EH: Yes, when you’re crossing over from room to room, you’ll basically hear them colliding.

CW: What a great space.

EH: I love it. The gallery was initially going to be somewhere else because China Art Objects hadn’t decided to move [to a new space in Culver City] yet. But the timing was perfect.

CW: And they feel so right in there.

EH: It’s the double rooms, and the lighting, and the loft. That space really thrives on natural light—it works perfectly.

I have an emotional history with that space, actually. I started the MFA program at Art Center College of Design in Fall 1999, when China Art Objects was first opening and so many of my peers were involved. It was the first space I ever heard about in Chinatown and I went to all their shows. It just felt special, and now it feels comfortable. They feel comfortable to me, too, Genevieve [Pepin] and John Ryan [Moore]. They’re warm and so grounded. We did a studio visit and I was saying I was going to take a break from galleries. I felt protective of how my art was changing and needed time to think about what kind of artist I want to be. But they came and I thought, “this is perfect.” It was like seeing someone from across the room and thinking “we’re a match.”

CW: Matching. That’s the story of your work right now: you looked back over the past two years and realized that things fit, but you hadn’t tried to impose that fit from the start.

EH: Right! It’s very Zen: loss of control, and letting things be.

CW: I liked the freedom I saw in those photographs of the Art Palace show.

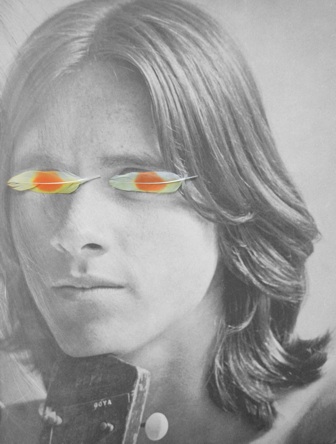

EH: Oh, Art Palace; I though you were going to talk about the feather photograph [Feather Eyes exhibited at Pepin Moore Gallery].

CW: Well, I liked that too. It surprised me.

EH: It’s hard for me to talk about. Before, my work was so researched, so conceptual, so when I would present a piece there was a whole history. I could say this is where it started, this is what it’s about.

CW: I know! Last time we talked, we went piece by piece, talking through each one’s history.

EH: That way of thinking about work began in grad school. When I first started at Art Center, I couldn’t verbalize what my intentions were, so the work evolved in response to that need to be put into words. But now I’ve shifted to talking about the process—where an image came from or how I came to put feathers on top of the eyes.

CW: It’s not a process of laboriousness, but it’s a cumulative process of—

EH: Years of making art.

CW: And living with the same ideas. There’s love; that’s a constant subject. And there’s always something that reminds me of the cosmos, and of the psychedelic.

EH: Yeah, it’s a little bit retro. It’s funny, when I was doing National Geographic collages during my Vermont residency, it wasn’t like I would go buy the latest issue. Instead, I bought one year’s worth of magazines, I think from 1973. The nostalgic appearance of my work has something to do with what happens when you’re looking back at a time; you’re able to pull things out of it that you can’t pull out of your own moment. Somehow, for me, the ‘70s or late ’60s is the perfect amount of time to look back on.

CW: Thirty-some years.

EH: Which is basically how long I’ve been alive. It’s the images of my childhood. Also, it’s a time that I associate with idealized change. Politically, in the art world, and in culture, people wanted to make real changes happen. There could very much be someone who’s radical right now but I can’t see it because I’m in this moment. With the past, you can edit out the failures.

CW: These ideas informed the work you exhibited this summer. The billboard at LAX ART, that was in June?

EH: So chronologically, I did the billboard in the month of June, and then Signs of Life at Richard Telles Fine Art, Country Music at Blum & Poe, Animal Style at Pepin Moore, and Long, Long, Gone at Leo Koenig Inc. in New York. At Koenig, there was a photo of a tape that plays endlessly. It’s a technology that was used in a lot of answering machines. TDK makes one that’s a 6 minute loop. So I took a photograph of the cassette, and then photographed it again, showing the inside, and that’s going to be exhibited at Pepin Moore. That’ll be the end of the road with that piece, the climax.

CW: The end of the endless cassette.

EH: Now that the work is more process-oriented, I keep going with it until it reaches a natural conclusion. Before, I never went back though sometimes, themes reemerged two or so years later.

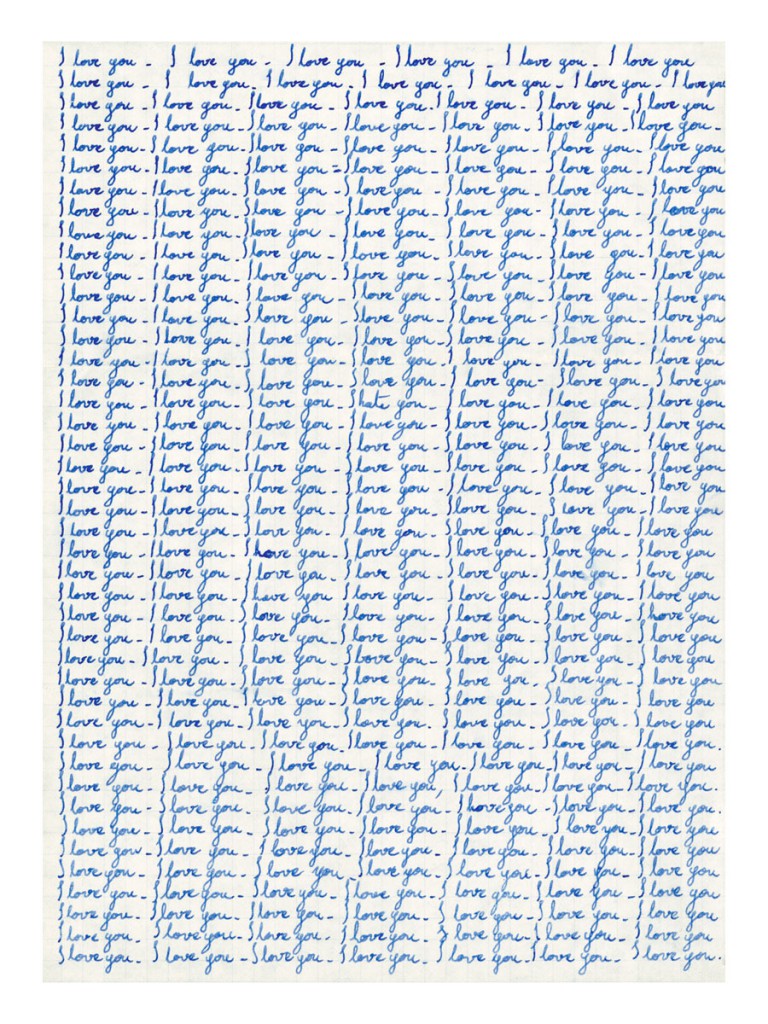

CW: The love letters in the Blum & Poe show, those were reemerging themes?

EH: There was Last Love Letter, which is the older one you saw in my solo show at Anna Helwing, and then there was First Love Letter, which I’d had all along, but had never shown. It’s actually the first love letter I received, scanned and printed. It’s from my 8th grade French boyfriend. It just says “I love you” over and over again but then there’s one “I hate you” that he hid.

CW: Did you notice it as an 8th grader?

EH: I saw it right away. I remember at the time it was just like the room had started closing in on me; everything collapsed. It broke my heart.

CW: But it was a love letter.

EH: But it said “I hate you.” And that was what I learned: it didn’t matter that it said “I love you” 100 times. All I could see was “I hate you.” When I asked him why he had done it, he said that he had wanted to make sure that I was paying attention and that I had actually read the letter, seen each word. The reaction I had and the logic that he had, somehow all of that informed my work so deeply. It was my introduction to love, and how love and hate could collapse so quickly. All it takes is one little drop, and you’re paying attention in a completely different way. The way I defined love for a long time was the way that letter had defined love for me. And, in some ways, that ended with the Last Love Letter photograph. My definition of love changed. It didn’t have be about longing for someone that was faraway, unrequited or painful.

CW: And the love letters were exhibited along with the little tape.

EH: So the tape is titled Lost Time. It’s the amount of time that’s lost every year. It’s 26.3 seconds of audio tape in a loop on a pedestal. Our Gregorian calendar is flawed, and there’s a little bit of time that is unaccounted for every year.

CW: You did a Lost Weekend piece [a stack of 540 images of a progressively disappearing mouth], but that was a while ago, right? At Project Row Houses in Houston?

EH: That’s a nice connection between Lost Time and Lost Weekend, actually. Lost Weekend is titled after what John Lennon called his Lost Weekend, which lasted almost 18 months. Yoko kicked him out, they were on a break, so he went to Los Angeles with Harry Nilsson, they wrote music but it was just a period of his life that was troubled with drugs and alcohol and he was away from Yoko. He had a girlfriend at the time that she actually approved of—

CW: Of course he did!

EH: He’s someone, the more I read about him, the more I realize he didn’t know how to be alone. But it makes for really good love songs if you’re consumed by the idea of having someone, and you exist in response to whether that other person is there or not.

CW: When Lost Time appeared at Blum & Poe, it was less unrequited.

EH: Like the time that’s not being accounted for, that piece is barely there and very ephemeral. In the press release for Country Music, Jeff Poe described the traces his grandmother’s hand had left behind from years and years of touching the wall when going up and down the stairs. That’s a very personal, emotional and yet ephemeral starting point for a show. The show was like his mix tape.

CW: You were on a lot of mix tapes this summer.

EH: And all of them worked, but each was completely different. At Blum & Poe, there was a black square in between First Love Letter and The Last Love Letter. That’s the distance that the moon has drifted from the earth since the last time we landed on the moon in 1972, approximately 5 feet.

CW: Really? And that’s the distance between the first and the last love letter?

EH: That’s a connection I had never made before. They are 3 separate pieces, and the decision to hang them all together was made [by Jeff Poe] in the curating.

CW: It’s your narrative that became his narrative and then became your narrative again.

EH: Exactly! It’s about distance, and time—time and space.

CW: I went to Thomas Solomon Gallery in July and he had this show of early conceptualists–John Baldessari (Season 5), William Wegman (Season 1).

EH: It sounds wonderful already.

CW: It was! It also included Lawrence Weiner [and Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, and Ed Ruscha]. Tom Solomon told me all these backstories—about knowing these artists when they first started, about their friendships. I remember thinking, “Early conceptualism is all about love.” These artists just wanted to make connection with each other. And yes, they were smart and heady, but they were communicating in the way that seemed truest to them.

EH: That’s an exciting thing to realize. Work that seems icy and removed can be filled with so much warmth. . . . When I was at the Vermont Studio Center, I met a poet who’s mother was from Brazil. She told me about how Macaw parrots mate for life, and if they lose their mate, they become suicidal and throw themselves out of trees. That’s when I started doing this Mate for Life body of work, and the first piece was just that single red feather coming out of the wall.

CW: Did you see the Supernatural show at Jancar Gallery? There was a piece by Baldessari from 1996. It’s just this mini-medicine bottle called Tincture—

EH: I saw that on your blog. I had never heard of it!

CW: It’s never been shown: Tincture of a Person Who Wants Everything. Apparently, Baldessari suggested it after reading Tom Jancar’s description of Supernatural: “objects produced to understand the larger world and control one’s position within it.” Wanting things and hoping object-making can help you get them, or help you learn how to exist, feels like what you’re exploring. Also, your work compulsively acknowledges that there’s a world beyond it.

EH: I want to say, come closer, come closer, and have this one small moment with this one small thing, but, all of a sudden, I want the experience to become so much bigger.