Traditionally, fall is the time when galleries launch their new slate of exhibitions after a relatively slow-paced couple of summer months. Galleries tend to highlight some of the most prominent artists on their roster around this time, but it’s also common to use the Fall slot to introduce promising new up-and-comers. In Chicago, at least, all the hoopla around the fall openings (many of which took place on a single night several weeks ago) can feel a lot like a high school pep rally: the anticipatory fall preview lists and gallery guides, the minutely detailed gallery crawl maps and the inevitable “best of” Tweets that follow are ways of rousing ourselves from the complacencies of summer in order to get psyched for the upcoming art season.

Kehinde Wiley, "Female Fellah," 2010. Oil on canvas, custom wood carved frame, 45 x 36 inches, 50.75 x 41.75 inches – framed.Courtesy Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago.

All hype notwithstanding, fall invariably works its magic on me. I struggle with lazy gallery-going during the summer (and, let’s be honest here, sometimes during springtime too) yet feel a sense of urgency about seeing everything once September rolls around. I’m pleased to report that my efforts have been richly rewarded this season. There are so many interesting shows, and quite a few really excellent ones, taking place in Chicago right now there simply isn’t space to do justice to all of them here. Let’s start with exhibitions by two artists who were recently interviewed on Bad at Sports‘s podcast. Kehinde Wiley, on view through October 23 at Rhona Hoffman Gallery, presented the latest iteration of his ongoing project World Stage: a series of portraits of young men of color from various cities around the world. Here, we find Wiley focusing on anonymous men from New Delhi, Mumbai and Sri Lanka, as opposed to the well-known rappers and athletes that had occasionally peopled his portraits in the past. Found through on-site “street casting,” Wiley’s subjects pose for photographs that the artist then transforms into grandly scaled history paintings; in so doing, Wiley points out the concerted omission of men of color from art history’s “world stage.”

During Wiley’s discussion with Bad at Sports’s Duncan MacKenzie, Richard Holland, and guest interviewer Dr. Amy Mooney of Columbia College, the artist claimed that his young male subjects actively participate in their own representation through their choice of accoutrement and setting. In this way, Wiley argues, his subjects “have agency” because they can determine the roles they play in their own fictionalization. But Wiley also admits that he has the final say: “the work is manipulated through digital means…the actual painting is where it really ends.” For my part, I’m still on the fence with regards to Wiley’s paintings, which tend to feel mechanical and, overall, a bit too slickly conceptual in their execution. Yet what I liked about this particular group of paintings was the sense of vulnerability and wary discomfort with our (and presumably Wiley’s) gaze these men seem to evince through their facial expressions, despite all the Photoshop machinations Wiley puts them through by the time they get to us. There are hints of real individuals here, buried under all the digital wallpaper and decorative filigree.

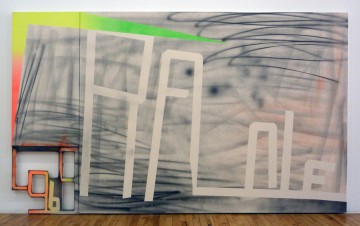

Wendy White, "Le Grau '96," 2010. Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 120 inches. Courtesy Andrew Rafacz Gallery, Chicago

Painting takes a more concrete and robustly physical turn with Wendy White’s swashbuckling abstract paintings at Andrew Rafacz Gallery. White’s approach strikes me as a post-painterly take on a classically Situationist enterprise: the urban dérive. She synthesizes a range of visual stimuli, such as neon lights glimpsed through grimy warehouse windows, billboard and poster typography, polyglot street fashion and post-punk graphic design, in a manner that’s idiosyncratic and intuitive. During White’s conversation with Tom Sanford and Amanda Browder of Bad at Sports, she explained that her use of air brush and spray paint started when “the brush actually touching the canvas stopped making sense for me. Ironically I feel the paintings have become more direct now that I’ve physically backed off from them.” White’s canvases also directly engage their settings: some are placed on the floor; others have cut-out portions in the shape of numbers or windows that give view to the surface of the wall behind them. White relies on gut instincts rather than conceptual directives to make her paintings; partly for this reason, she tends to complete each canvas in a single go. “They’re very much a record of a moment, a time period…three or four hours for the big ones,” she said. This is the first time the New York-based White has exhibited at Rafacz’s gallery in Chicago. (You can find additional installation shots from the show on White’s website).

Dan Gunn, "Multistable Picture Fable," 2010.Acrylic, enamel, glitter, glue, colored pencil, plexiglass, ribbon, furniture, basket, lycra, marbles, on plywood, panelboard, particleboard and wood with hardware.Dimensions variable, approx. 8' x 15' x 6'. Courtesy the artist and Lloyd Dobler Gallery, Chicago.

Like Wendy White, Chicago artist Dan Gunn makes objects that challenge normative ways of looking at a flat surface. Gunn’s extravagant, enveloping installations aren’t paintings, although I find it perversely pleasurable to think of them in precisely those terms. Titled Multistable Picture Fable, Gunn’s small solo show at Lloyd Dobler Gallery consisted of a sculptural environment composed of individual flat panels of various materials and sizes that are hinged together like doors, fences, or, to my mind, run-on sentences.

Multistable Picture Fable makes me think of makeshift wooden forts and secret hideaways. The installation must be walked around (and around and around) in order to be apprehended. At one point, the hinged panels seem to rise up and swirl around your body, creating an inviting private alcove that encourages the kind of intimate consideration of form and surface that institutional art presentations, with their warning signs and “don’t touch!” admonitions, hardly ever allow. Each panel is wildly different from the next: some are painted, some have paintings affixed to them; some are curtained by fabric, others are stained or left bare, the better to show off the integrity of the original surface. The panels echo each other and converse, and invite you to do the same. If, for argument’s sake, we do choose to view these objects as paintings, we find distinctions between inside/outside, back/front, surface/support becoming unstable and ultimately losing their grip on us entirely. They’re exposed as fictions, or “fables,” as rules that are meant to be broken.

Edra Soto, installation view of "Homily" exhibition. Left: "In Memory Of Our Sentiment (mausoleum)," 2010. Right: "The Triumphant Vessel," 2010. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Foreground: "Communion II," 2010. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and ebersmoore, Chicago.

Edra Soto, "In Memory Of Our Sentiment (mausoleum)," detail, 2010. Wood and steel, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and ebersmoore, Chicago.

In an exhibition titled Homily at ebersmoore, Chicago artist Edra Soto reinvests religious iconography with personal symbolic meaning. Soto, who was born in Puerto Rico, makes weird and wonderful sculptures, paintings, and drawings that celebrate the myriad forms that love takes, whether it’s romantic or familial love, the adulation of celebrity, religious devotion, or the unconditional love that pets have for their “people.” In this exhibition, Soto has re-imagined ecclesiastic gathering spots familiar to Catholic Church-goers–the mausoleum, the Stations of the Cross, the Eucharist–on her own terms. A large, slanted staircase painted bright blue looks like a Minimalist sculpture, but the white hand rail that Soto has thoughtfully provided quickly gives its true purpose away: these entirely functional stairs are meant to be walked up or sat upon. When viewers make their way up the steps and peek over the top, they find a glass-topped case containing four skulls: two human, one of a dog and another of a cat, all “planted” in a bed of earth and surrounded by cactii. Soto tells me this represents her immediate family in Chicago, her husband and family pets whom she holds closest to her heart. Next to this, a tall form swathed in a paint-spattered white shroud holds up a tower of champagne glasses filled to the brim with blue paint, which has splashed from the top and onto the wall beside them. Soto has also reinterpreted the Stations of the Cross as an intimate family devotional that honors her mother- and father-in law, her husband, and of course her beloved dog. By placing these works within an art gallery, Soto also seems to suggest that art and its institutions provide another outlet for expressions of love and devotion. Fittingly, Soto used the second room of the gallery as a group exhibition showcasing three young artists whose work she admires: Corinne Halbert, Thad Kellstadt, and Carmen Price.

I’ve run out of time, space, and most certainly your attention, yet there’s so much more happening in Chicago this Fall to share! Please keep your ears tuned to Bad at Sports’s podcast over the next few weeks; we’ll be interviewing Dexter Sinister on October 10th (Episode 267), who are currently exhibiting at UIC’s Gallery 400; Dutes Miller and Stan Shellabarger (Episode 268), whose show will open at Western Exhibitions next month, and Luc Tuymans on November 7th, (Episode 271), whose big retrospective opens at the MCA Chicago in early October.

Pingback: Four for Fall | Centerfield on Art:21 blog : Bad at Sports