Still from Peter van Bagh's documentary, "Helsinki Forever," 2008. Courtesy the Finnish Film Foundation.

I didn’t sleep much in Helsinki. Though it was my second trip there and my umpteenth time in the Nordic countries, I somehow booked my travel to coincide with Juhannus, Finland’s midsummer. Simply put, midsummer is the annual summer solstice, falling in or around June 21 each year. We Americans give this seasonal astronomical event an acknowledging nod or, if we’re feeling festive, a bbq. But for Finns, Juhannus involves a mass exodus from civic and economic duties, as droves of city mice evacuate the capital for their country homes and a pre-lapsarian return to the simple life. In Finland, at least, this consists of gigantic, competitive bonfires, endless sauna-ing and dips in the frigid North Sea, lots of drinking and weird Estonian liquor, and grilled things.

This past year, I curated a touring film program called “Package Deals: Finland” and this summer, I returned to Helsinki to get a deeper, closer look at what contemporary Finnish art and cultural policy look like. I will go into more detail about the artists I met, spaces I visited, and artwork I experienced in future posts but since I’m setting the scene here, I’ll start with my home during my two-week stay: Suomenlinna and its tenants, the Helsinki Artist-in-Residence-Programme, or HIAP.

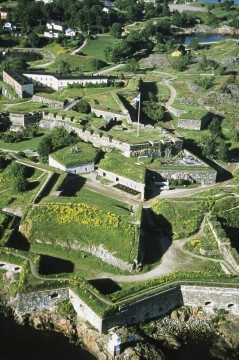

If you make your way through the Kauppatori market at the tip of Helsinki’s harbor, resisting an unbelievable array of berries from Lapland (including these), reindeer skins, and fried herring, hop on a short ferry to one of Europe’s most incredible landscapes: Suomenlinna, or Sea Fortress. Fifteen minutes out in the Helsinki archipelago, this group of eight islands — and UNESCO World Heritage Site — is home to an old fortress and a still-operational Naval Academy training recruits to protect Finland’s 800-mile eastern border with Russia. Suomenlinna, as my new Finnish friends told me, is also home to a prison and rumored to be haunted (which did not allay my solitary midnight walks from the ferry dock back to my residence).

I visited as a tourist here in summer 2009, a friend and I then weathering our traveler’s exhaustion on cliff rocks and posing with old cannons. This time, I had booked a room as a researcher in HIAP’s residency housing for two weeks. Each evening after a day filled with meetings and art-viewing, I took the ferry back to Suomenlinna, walked the 15 minutes to my temporary home on Susisaari island, and took stock of my surroundings. Staying at HIAP was, as with most artist residency programs, like being in art camp. The residences, divided into researcher housing and studio spaces, neatly lined up one side of an open courtyard replete with playground. Unlike other art camps, however, this one dated back to the 18th century and was surrounded by the Baltic Sea.

Though currently Helsinki’s main artery to contemporary art, HIAP hasn’t always been the only game in town. FRAME, the Finnish Fund for Art Exchange, was the largest supporter of the country’s contemporary artists until its operations came under fire from the government last year. FRAME organized exhibitions at home and abroad, published Framework magazine (the Finnish Art Review), and patronized artists via Finland’s enviable welfare-state system. HIAP originally functioned as the outward-looking complement to FRAME’s homegrown support, welcoming artists from abroad to enrich Helsinki’s art scene, introducing new ideas and contacts to artists working in Finland — essentially in an act of cultural diplomacy.

With FRAME’s future now uncertain (the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture will set out new guidelines by year’s end), HIAP is quite possibly poised to pick up where FRAME left off. Founded in 1998 by a coalition of various Finnish arts organizations, HIAP experienced a major growth spurt beginning in early 2007 after NIFCA — the Nordic Institute for Contemporary Art, a pan-Nordic cultural council of sorts, serving all 5 Nordic countries — had been shut down by the Nordic culture ministers in an attempt to privatize what they saw as bloated cultural bureaucracies (almost 20 other organizations also got the ax). NIFCA moved out of Suomenlinna, leaving its own artist residencies behind. FRAME administered the spaces for a few years and then the Ministry of Education and Culture invited HIAP to take over. HIAP functions on a budget of a little more than fifty million euros (almost half is public funding from the Ministry of Education and Culture, Arts Council of Finland, and the city of Helsinki; the rest comes from Finnish private foundations and Nordic and international sources). With a second residency in Kaapeli (the Cable Factory) on the western side of Helsinki and exhibition spaces both there and on Suomenlinna, HIAP’s staff of seven houses and exhibits a rotating cast of roughly 60 artists from Finland and abroad year-round, and another 70 or so through its public programming.

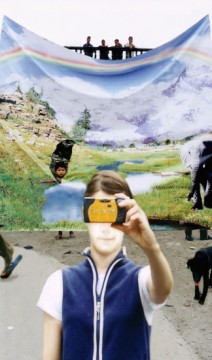

Stuart Hawkins, "Disposable Camera," 2005/2006. Customs: Series of C-Prints 10 x 5 inches, 25.4 x 12.7 cm. Edition of 3. Courtesy Zach Feuer Gallery, New York.

On an invitation from the governing body of Suomenlinna, HIAP had recently reopened Gallery Augusta, a large cavernous space left over from the NIFCA days. Built in 1866-68, it has been used variably as a soldier dorm, prison camp, civilian apartments (with sauna and laundry), and storage space. When I was there, the excellent Snapshots of Tourism, an exhibition curated by HIAP’s Marita Muukkonen and former chief curator of Kiasma, Maaretta Jaukkuri, was on view. On a tour of the show, Muukkonen explained how the works — made by international artists who had all, at some point, made art in the Nordic countries — questioned the “touristic gaze” in our complicated global landscape. To see pieces by Amar Kanwar (India) and Cildo Meireles (Brazil), in dialogue with work by well-known Nordic artists like Jeppe Hein and Jens Haaning was a testament to Muukkonen’s and Jaukkuri’s curatorial sophistication (notably, however, the show featured only one Finnish artist).

HIAP also serves as a cultural ambassador to its tenants. Prior to the midsummer exodus, all us residents and guests, along with HIAP’s staff and their families, boarded a tour bus and headed four hours north to an annual regional art festival in Mänttä, in central Finland. At the festival, housed in a giant warehouse-like hangar, we explored the work of 49 artists working across the country. Standouts included artists Sami Sänpäkkilä, Anneli Nygren, Anssi Kasitonni, and Vappu Rossi. The exhibition, organized by guest curator Annu Vertanen, was seriously over-installed — the plethora of work diluted the overall viewing experience and made it difficult to remember what I had just seen. This may be the Achilles heel of the regional art festival’s pluralistic attempt to please all. However, I appreciated Mänttä’s version nonetheless for the varied experience of contemporary Finnish art it offered, most of which was new to me anyway.

After a few hours in Mänttä, the June sun blazing into our skulls, we ventured across town to a private house-turned-museum, Honkahovi. Living in Chicago, I confront the legacies of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe on a regular basis. Yet at Honkahovi, I was still enthralled with the space and the works on view. Honkahovi’s modest yet smart summer exhibition, Slowly but Surely, was a proposition of how to slow down our frenetic lives to a meditative amble. With its sculpture-laden grounds reminiscent of Copenhagen’s superb suburban art museum, Louisiana, I thoroughly enjoyed the dichotomy of very contemporary art installed in a mid-century home (the house was originally built in 1938; once private, it returned to public hands when the owners passed away in 1991). Here, I got a taste of a different, quieter curatorial practice—one clearly not striving to please all save the few fortunate visitors that seek out this charming, out-of-the-way place.

Finally, a long day of bus-riding and art-viewing behind us, the residents and I landed back in Helsinki exhausted and starving. What better way to end a Finnish cultural pilgrimage than with national cuisine? Feasting on cabbage rolls and guzzling mugs of Lapin Kulta beer, we marveled at how we — an unlikely group of artists and administrators from Australia, Ireland, Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, and elsewhere — were privy to Finnish culture on a scale and in locations inaccessible to most foreigners. The admirable team at HIAP brought us together, one group among many they foster all year long. After dinner and yet another ferry ride back to the island under the midnight sun, I briskly trotted through Suomenlinna’s tunnels back to my apartment. The cobblestones massaged my feet while I tried not to think about the ghosts rumored to be in those tunnel walls.