I am happy to once again be blogging for Art21. This is the first of three posts loosely based around contemporary art from/in Latin America.

Living in a city other than New York means that visits to it become shameless frenzies of nonstop art viewing. Every new show and space that has sprung up in one’s absence must be experienced, lest an essential trend or development be missed. One of my favorite stops on my summer treks there was the recently opened Henrique Faria gallery on East 67th Street. Faria, who previously ran Art Cabinet on Madison Avenue, has used his first few exhibitions in the new space to define an intriguing sub-genre within Latin American conceptual art that is sure to receive increasing attention in coming years. In contrast to the better-known, participatory examples of conceptualism from the region—Tucumán Arde (1968) in Argentina, Cildo Meireles’s Insertions into Ideological Circuits (1970) in Brazil, CADA’s street-based protests in Chile (late 1970s-early 1980s)—these more cerebral practitioners favored photography and language-based works on paper. On first glance, their work hews closer to the North American and European “conceptual art” that Uruguayan artist Luis Camnitzer distinguished from Latin American “conceptualism,” but they were no less focused on the disastrous political events unfolding around them in the 1970s, and it is this subject matter that creeps into their displays of language and information.

The show that I saw at Henrique Faria in June was Horacio Zabala and Margarita Paksa: Analogies and Differences. These two artists’ oeuvres make a fruitful comparison with Juan José Campanella’s recent film El secreto de sus ojos [The Secret in Their Eyes], which won the 2010 Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. All three provide narratives of just before and after 1976 in Argentina, when a right-wing military junta overthrew the government and ultimately disappeared some 30,000 people. Campanella frames the period through a police procedural: a detective tracks down a perverse killer who, once the junta comes to power, is released from prison as a member of the death squads in Ford Falcons who are assassinating “subversives.” The widower of this killer’s original victim is found, decades later, to have kidnapped him and kept him alive in a barn on his property. This is an allegory for holding onto bitterness and trauma: victim and victimizer alike remain chained together, unable to move forward. At the beginning of the film, waking from a nightmare, the detective scribbles temo, or “I fear,” on a pad, yet by the end he is able to transform it into te amo, “I love you,” through the addition of a missing “A” for Argentina—a suggestion that the trauma has been “worked through,” the dark period and its mysteries behind us.

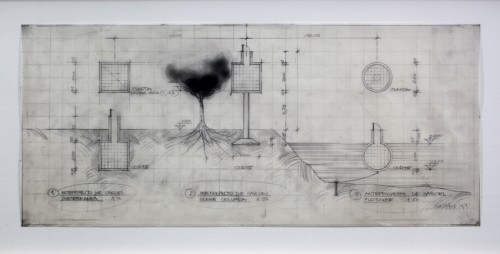

No such consolation is to be found in Zabala and Paksa’s works from this period. Apocalyptic and bitterly humorous, Zabala’s Anteproyectos [Blueprints] were produced while he was associated with the Centro de Arte y Comunicación, one of the few venues for progressive art in Argentina in the 1970s. The Center’s galleries in Buenos Aires were constructed underground in futuristic, bunker-like spaces. Its stable of artists, which included Víctor Grippo and Luis Benedit, developed their works through blueprints and architectural plans that were exhibited alongside the finished products. Zabala dispensed with the result and exhibited only plans: fantastical structures designed to protect one individual at a time from disasters such as floods or atomic bomb detonations that described as much prisons as sources of safety. The Center itself seems to have been a point of reference as an art venue that, to keep exhibiting in a state of emergency, effectively sealed art off from the outside world.

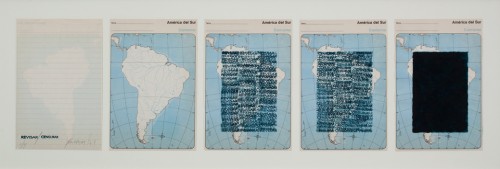

In this series of works on paper, Zabala gradually covers a map of South America with ink-stamped words revisar and censurar: “to revise” and “to censor.” When Holland Cotter, in his New York Times review, observes that both of these artists have “limits,” he is referring to the apparent bluntness of this phrase, but it is in Zabala’s exertions of the hand—now meticulously drawing, now pounding—that he goes beyond mere protest message to use form and media themselves as instruments of impotent rage.

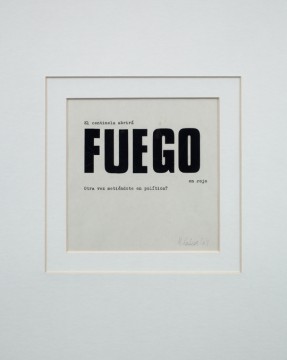

Paksa appeared in the Buenos Aires art world before Zabala, having produced both sculpture and participatory works from the mid- to the late 1960s. In 1968 she was involved with Tucumán Arde, the now famous collaborative anti-dictatorship protest staged by a host of artists, journalists and activists. Yet her subsequent text- and information-based works share neither the silence of her quasi-minimalist sculpture and environmental actions nor the direct and clear messages advanced by Tucumán Arde-style political art. One produced soon after seems to express ambivalence about the possible consequences of political action, reading “The sentinel will/ FIRE/ in red/ Getting yourself into politics again?”

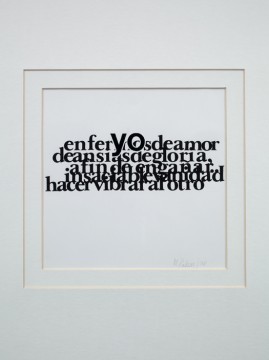

Paksa’s works on paper from the late 1970s were produced during years of worsening crisis and repression, and situate the trauma of violence and disappearance at the level of text and communication itself: sentences are subjected to distortions that interrupt or destroy their legibility. A particularly devastating work of 1973 (not pictured here) memorialized the barbaric torture suffered by the singer Victor Jara, a victim of the Pinochet coup in Chile. It reads “me erc/ or taron../ la as/ manos,” a poetic fragmentation of the phrase “me recortaron las manos,” or “they cut off my hands.” This work hails from Paksa’s Sin foco (Out of Focus) series, in which language’s very ability to bear witness to atrocity is in mid-collapse.

Henrique Faria’s new group exhibition, its first in a newly doubled gallery space, is titled Latin American Conceptualism I and was on view until October 9. The gallery will also be hosting an exhibit on Venezuelan conceptual art for the Pinta Art Fair in New York in November.

Daniel Quiles, a guest blog alum, is Assistant Professor of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago.