A hair was stuck in the main camera when Liza Minnelli first filmed Liza with a “Z” (1972), a supposedly live special for NBC. Minnelli and crew refilmed, using paid extras for audience members. Biographer Scott Schechter tells this story in The Liza Minnelli Scrapbook, and critic Bruce Hainley retells it in “Just Say Yes,” a painfully tender essay which suggests Minnelli said yes to the “‘brilliance, bisexuality, and betrayal’ she was born into.” Yet saying yes leads her into an obsession with feeling that she is “live” (or alive), rather than “living proof” of a legacy only part her own, and micro-managing how the shards of her complicated cultural identity reach audiences. Broken by culture, she lives in a constant state of “fixing herself up.”

Minnelli could easily inhabit Lari Pittman’s world. A virtuosic micro-manager, Pittman (Season 4) thrives on brokenness, using shards of culture as currency, piecing together glassy seas of artifice until they become, like Minnelli’s live performances, “shameless, intoxicating” (to borrow Hainley’s words) proof of life.

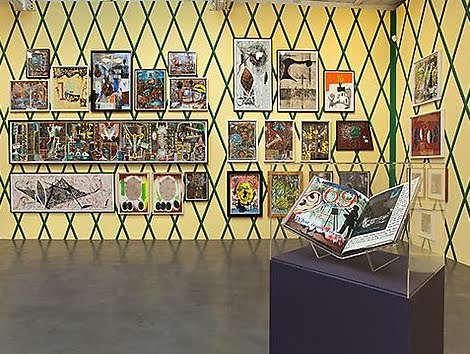

As an artist, Pittman is brutally generous. Each painting represents so much time, energy, decision-making, and rendering that it feels like both a hand-wrapped gift and a vicious affront to the natural world, an alternate landscape you could fall into if you found the organic too spontaneous. For his current dual exhibitions at Regen Projects in West Hollywood, Pittman has filled two galleries. The first exhibition, titled Orangerie, has orange-yellow painted walls with green crisscrosses and functions as a sort of self-curated retrospective.

Orangeries, conservatories originally meant for citrus, tended toward architectural excess in the 17th and 18th centuries–Louis XIV had one at the Versailles that housed 3000 orange trees and sported Neoclassical columns–and their function often seemed secondary to style. Pittman’s is all style. Prints and paintings that span his career hang salon style, and there are books in vitrines. The most brutal of his work seems to be in this room. Mix Vigorously and Ingest (#4), which makes personality, body and nourishment indistinguishable, includes chalices of Charm, Cilantro, and Semen along with an inordinate number of light bulbs; and As a woman of 60, I will have revealed the decor of my interiors, in which ornate test-tubes, x-rays, and accessories crowd into each other, turns growing old into manufactured rebirth.

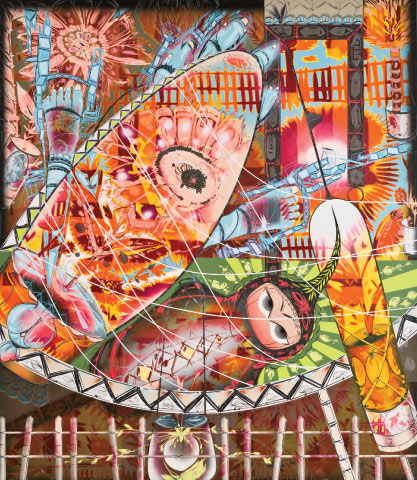

When featured in Season 4 of Art:21, Pittman talked about coming to painting in the 1970s, when artists distrusted if not derided the medium. “I was thrilled that [painting] was abandoned,” he says, “and that I maybe had a chance to fix it up.” He took this to an extreme, adopting art-historical and cultural imagery like a sort of den mother whose children “sprung fully formed.” He’s the overbearing parent of beings he didn’t bear. And in these current exhibitions, his cut-outs, decorations, glassware, religious icons, table cloths, movie stars, webs, and tapestries are not only fixed up but nearly grown up.

In the second gallery, across the street from Orangerie, Pittman’s newest paintings hang at fairly equal distances from each other. They’re sometimes too even-handed and at home in their density, but this seems like something that was bound to happen. If you resist nature so thoroughly that not even a hair can flit across your lens, your world is bound to become so self-contained and comfortable with itself that it begins to feel natural.