Annika Strom's "Ten Embarrassed Men" at Frieze 2010. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian

As part of this year’s Frieze Art Fair, Simon Fujiwara, the winner of the 2010 Cartier award, has conjured up a faux-archaeological Roman site, bits of which are sometimes exposed in the main body of the fair. It’s all genial and non-threatening fun-poking (there’s the unearthed house of a female collector, full of coins and an archaic handbag; you get the picture) and makes enough winking references to make the cognoscenti feel good, so it’s not much of a surprise why he won. This, by and large, is the tone of a selling event that has transformed itself into a cultural one. Disingenuous self-deprecation abounds, aimed at both the skeptical outsider and the knowing insider.

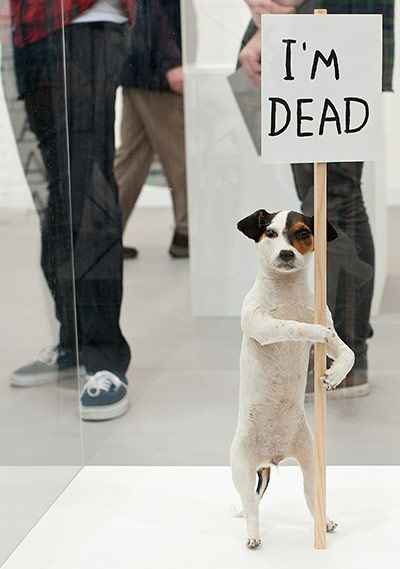

Much funnier is Annika Ström’s Ten Embarrassed Men, a group of identically dressed middle-aged actors, who huddle around en masse looking awkward, organized by the artist as a response to the representation of women in art fairs. How it really works is by providing a welcome bum note to the atmosphere of overweening economic confidence (however hyperbolic) that surrounds it. David Shrigley’s stand at Stephen Friedman Gallery is, as you’d expect, properly LOL-funny, which makes his presence at the art fair a bit anachronistic, and his appropriation by the art mainstream an ongoing puzzle. The artist himself was in attendance, painting temporary tattoos on people’s arms. I watched him slowly paint a fly on a man’s forearm. Everyone looked on, looking serious, filming on their phones.

David Shrigley, "I'm Dead." Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images.

The overwhelmingly enormous nature of Frieze means you have to take a systematic approach to exploring it, which also means that your critical faculties become subsumed to geographical/social anxiety. Have I been here yet? Is that the person with the asymmetrical fringe I saw two minutes ago, or another person with an asymmetrical fringe, and have I been staring at her for too long now with a wrinkled face, and why is she coming over looking cross? The preponderance of things made out of mirrors and/or neon and what was either a huge number of late Baselitz paintings, or one or two late Baselitz paintings that I kept accidentally returning to, made the whole experience Inception-like in its mind-twanging intensity. Luckily there were more than a few little islands of visual enjoyment that justified the queuing – but not the cost, which has shot up to a pretty shameful twenty-five pounds. I have no idea how they justify that, unless that’s another artist commission I wasn’t aware of. LOL – twenty-five quid! For this! (I get it).

Respite from the sea of ice-cream hair and architectural spectacles was provided by works by Richard Tuttle at Stuart Shave, Ryan Gander and Haroon Mirza at Lisson, Des Hughes’ mad medievalism at Ancient and Modern and Tala Madani’s painterly animations at Pilar Corrias. Elizabeth Dee’s display of current queer theorist (queorist?) favorite Ryan Trecartin proved him to be not the academic inside joke I’d expected, but an hilarious and totally engaging heir of Pink Flamingos-era John Waters.

As ever, though, the delights of Frieze are in watching the art world at work, like peering into an anthill after you slice the top off with a spade. One New York gallery used adapted skateboards as seating, hilariously. And in one gallery, I watched a piece made of angled sheets of glass get slowly cracked and smashed by important-looking visitors, as the gallery staff apologized to them for it being in their way or something.

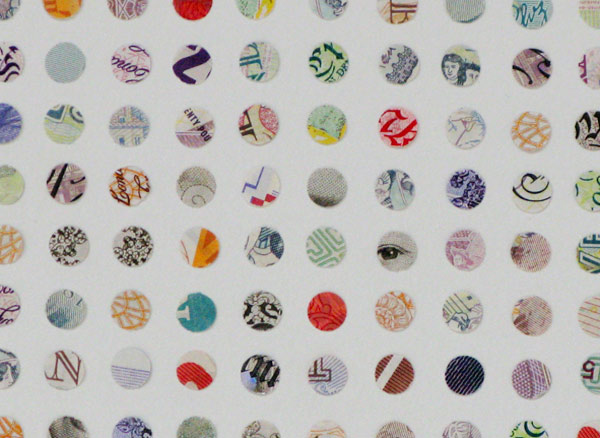

As ever, the peripheral fairs provided greater artistic and fewer satirical delights. The Sunday art fair (a sort of replacement for the now-defunct Zoo Fair, and an alternative to Frieze’s designated new gallery area, Frame) in a cavernous space underneath the University of Westminster, provided alternative viewing conditions for less established galleries. Eschewing the temporary walls that underscore Frieze’s hidden identity as a trade fair, duct tape on the floor created divisions between gallery spaces, much like Tate Modern’s disappointing No Soul For Sale from earlier this year. Whether it was due to its alternative to Frieze’s exhausting slickness, or the quality of the work on show, the Sunday fair felt like a balm in comparison. You wonder whether the often great work on display at Sunday – video and sculpture by Edwina Ashton, a slideshow by John Smith, a tub of badges by Ryan Gander – would have been swallowed up or muted by the thrum of the marquee in full swing. The most emblematic work at Sunday was by Jack Strange at the Limoncello stand: small circles made by hole-punching paper money, displayed in a Hirst-style grid, entitled “£2025”. He couldn’t get hold of enough money to make it bigger, apparently, which was the nicest thing I heard all week.

Jack Strange, "£2025," 2008-ongoing. Single Hole-Punches from £5, £10, £20, £50 Notes. Courtesy Limoncello Gallery.