Art21 is pleased to announce our latest column: 5 Questions (for Contemporary Practice), written by guest blog alum Thom Donovan (bio here). 5 Questions showcases the work of contemporary practitioners across the arts and other forms of culture work, such as publishing, activism, curation, education, criticism, writing, and scholarship. It will regularly present participants’ responses to a basic questionnaire, followed by elaboration, analysis, and engagement with the work of the participant. Through this column, we hope to sketch a constellation of practitioners who are shaping a discourse about art in relation to cultural politics and social responsibility. The first installment is Thom’s interview with Chicago-based artist collective Temporary Services. — Ed.

1. What inspired you to start Temporary Services?

Temporary Services started in 1998. This was a time in Chicago when a lot of not for profit and/or alternative spaces had closed or were closing. This atmosphere was due in large part to the gutting of funding to these kind of spaces from the National Endowment for the Arts in the wake of the Culture Wars. All the spaces that supported non-commercial, experimental, political, and otherwise more free ways of working no longer existed in our city. This cleared the way for new models of presenting and supporting artists’ work.

Surveying the commercial gallery situation, none of us could imagine putting our work in these spaces or that they would be an interesting means to presenting art and ideas in our city. We still feel this way about most commercial galleries.

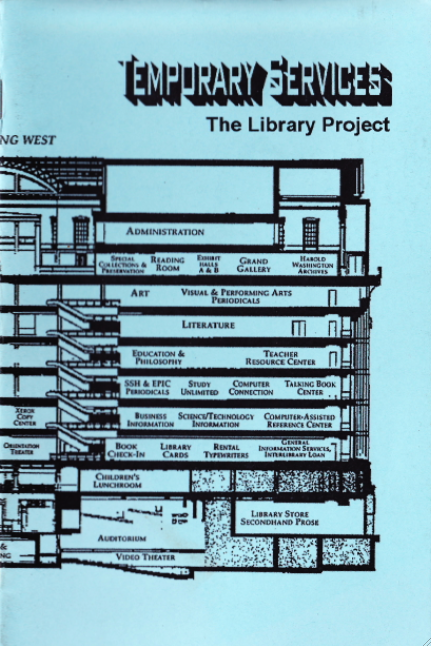

Temporary Services started as an exhibition space in a tiny storefront on the 2800 block of North Milwaukee Avenue — a working-class area that was not a hub for art activity and where our presence was quite ambiguous. Our name, which pointed to the ephemeral nature of some of our projects, as well as the idea that art could be a services to others, blended in with other peculiar businesses and service-oriented storefronts in the neighborhood. In less than a year, the space morphed into a larger collaborative group that at one point numbered seven people. Even while we inhabited this space, we often staged projects on the sidewalk or at different sites. In 1999 we left this space, took on a new office space in downtown Chicago, and then left that space again in 2001 — always while also using other sites as needed and dictated by our ideas for each project. One of those sites was the Harold Washington Library Center, just down the street from our loop office, where we added 100 books by artists and others to the collection without permission (The Library Project).

Back then, and to this day, we were looking to try out new ways of working amongst ourselves and with others, new approaches to presenting art and creative activity, and new sites and contexts that might aid us in expanding the audience for experimental art — by ourselves and by participants in projects we organized, like the aforementioned The Library Project.

2. Why do you feel there is a need for organizations like Temporary Services, which produce aesthetic objects and actions that intend a direct effect upon their social contexts (if that’s how you’d describe what Temporary Services does)?

This partially describes what we do. We work in many different ways. We give ourselves a lot of freedom to not create a formula for cranking out aesthetic works (insert the name of your favorite or not-so-favorite gallery artist here) as well as not branding ourselves by concentrating too much on the group identity (insert the name of your favorite activist art group here). We actually try to fuck with these things directly from time to time to keep things very open and free.

There needs to be a ton more projects, collaborations, and other experimental configurations for artists to really push art out of its incredibly stagnant, decadent, boring-ass position in the world. The commercial market needs to be abandoned on a massive collective scale and artists need to stop relying on others exploiting them to be the definition of how art is made and received. Market-based art forms have only been around for a very short period of time, though everyone pretends that they are an inevitable, natural thing that isn’t to be questioned. The focus of the discussion is often on individual artists and this doesn’t reflect the explosion in the numbers of groups and people who want other ways of working beyond the modernist clichés.

We simply want to support and encourage anyone who finds other ways of putting their art into the world. Hopefully they find ways other than how we do so it increases the diversity of ideas and the possibilities of interesting, challenging aesthetic experiences.

We also feel that there needs to be some counterweight to the horrible educations often being given to artists. Art departments in colleges and universities are often overly-individualized, conservative, market-oriented, and not at all about nurturing and teaching people to find new audiences, to make art relevant in daily situations, to find some way out of the specialist trap of splitting aesthetic hairs. So many artists emerge from their education and immediately get bogged down in this game and think this is what they should be doing to either get an income or respect.

3. Are there other projects, people, and/or things that have inspired Temporary Services (past or present)? Please describe.

All three of us have different personal influences, musical tastes, and political and active leanings that sometimes overlap. Some of the many things that we all agree are inspirational and inspire us: Chicago histories of socially engaged practice that include Haha and their project FLOOD, and the late artist Michael Piazza and his pioneering collaborative and community-based work in the city. Also the many great groups that are active in our city today including Mess Hall (an experimental cultural center in Rogers Park that we co-founded but no longer co-run), the group InCUBATE, the newspaper AREA, Feel Tank Chicago, and Dan Peterman and the Experimental Station. Groups outside Chicago include Group Material, Guerrilla Art Action Group, Act Up, and Ant Farm as well as the Danish groups N55, Learning Site, and Superflex. We are particularly drawn to groups that actively write and self-publish.

We are huge music fans and draw a lot of inspiration from seeing how groups organize themselves. The Dutch band The Ex is one of the most important influences on our group. Punk rock, filthy heavy metal for its visceral power and lack of irony, and experimental musicians who self-release and distribute their own music and take an active role in its placement in the world inspire us greatly and you can still find us, sometimes accidentally these days, in mosh pits.

Of course there are political influences like The Weather Underground and The Diggers, the glorious long history of anarchist thought and action in Chicago dating from Emma Goldman, Lucy Parsons, up through anti-corporate-globalization organizing of the late 90s early 00s.

4. What have been your favorite projects to work on and why?

When asked during a lecture which film of his is his favorite, the American documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman — who all of us greatly admire — responded that this is like asking which of his children is his favorite. None of us have children, but we have dozens of projects to consider. Each brings with it different challenges, parameters, sites, experiences, and people. Usually presenting a project for the first time — coming up with the ideas and solving the creative problems specific to a work or a particular situation — is the most challenging and creatively exciting. Showing an old project in a new place for the first time also has its rewards and challenges too because different works sometimes mean very different things in different places and commonly need a bit of an overhaul or an expansion in order to stay relevant to us or their audience. We’ve had the opportunity to work with a lot of amazing people all over the world — sometimes repeatedly.

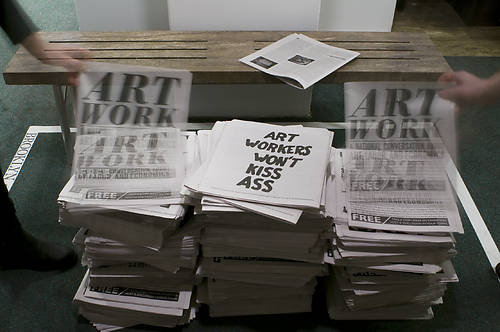

Perhaps our favorite part of the way we work is feeling plugged into an extraordinary and continually inspiring loose knit international community that we can draw on and call into action as ideas necessitate. A recent example of this was the newspaper and website, Art Work, about the sorry state of the economy and how it is impacting artists throughout the U.S. We initiated this project at the invitation of the organization Spaces in Cleveland. From there, more than fifty people contributed writing in print and online and dozens of additional exhibitions, discussions, and events have been organized throughout the U.S. and overseas by contributors and others that felt moved to get involved. It has been inspiring to see what can happen when you loosen the reigns and let others take charge of an issue that deeply matters to them.

5. What projects do you see in the future for Temporary Services? What direction would you like to take the organization in?

We are addicted to self-publishing. Since founding our publishing imprint and webstore Half Letter Press, we have increasingly taken on the publication and distribution of work by others. Temporary Services’ interview booklet series, Temporary Conversations, will continue with the publication of a new interview later this month: Nicolas Lampert speaking with Aaron Hughes of Iraq Veterans Against the War. Soon after that, we will release a book by Mary Patten on the Madame Binh Graphics Collective — a radical, active, printmaking, street art, and postermaking collective with all female membership based in New York City between 1975 and 1983. A book on Mobile Structures — mobile and portable modes of working created by ourselves, other artists, service-based groups, and individuals seeking new audiences, is also in process.

Other projects include exhibitions of an inspirational book collection we curated: the Self-Reliance Library, and a new project titled Designated Drivers, where we’ve asked 25 artists, musicians, curators, and groups to each fill a 4GB USB flash drive with content of their own choosing that exhibition attendees will be able to import into their computers or explore on a host computer and burn onto CDs and DVDs.

Our projects continue to vary in scale and scope, often including other participants who might not get similar opportunities otherwise. Our group structure has been fixed with the same three people since 2002 (Brett Bloom, Salem Collo-Julin, and Marc Fischer) but we continue to take on new projects with additional collaborators whenever we see fit. Our practice remains flexible as ever — an important thing given the funding limitations for art practices that happen outside of the commercial art world. Still, Half Letter Press continues to grow as both a publishing body and a distribution center for limited and self-published materials that we think are important.

We are grateful for the experiences and opportunities that group work has brought us and are committed to helping create mutually beneficial systems of support with others who we respect, old friends and new.

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

I first came across Temporary Services’ work browsing Printed Matter bookstore in Chelsea, NYC, where I discovered the group’s Temporary Conversations interview booklet series and their anthology of quotations about collaboration, Group Work. Since then, I see their name everywhere, and hear it on the lips of countless friends and colleagues.

I guess you could say that I’m a fan of what Temporary Services does but also what they stand for, which is the freedom that art can still allow the individual among others and within a public realm. As Temporary Services say above, their work attempts in various ways to challenge the strictures of the current art world and art market, an economy that tends to work against collaboration, use values, and social transformation.

Interestingly, Temporary Services, while they have received a fair amount of attention from mainstream art critical sources in recent years, have remained committed to the initial goals of their group project. These are to provide service to their communities, to free art from the economic and institutional clutches of a larger art world, and to provide their audience (who are also often participant in their projects) with a sense of agency and permission to explore social and public spaces through aesthetic means. It is also to elevate many “aesthetic means” that are currently eclipsed by the hegemonic values ascribed to art.

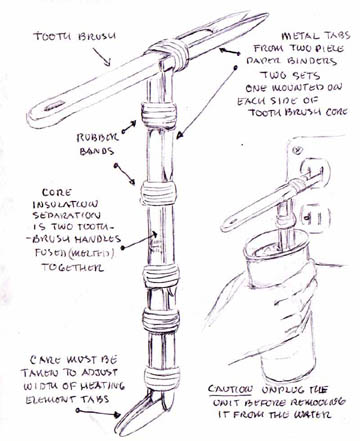

One of Temporary Services’ most popular projects in which they challenge these values is their collaborative work with Angelo, a visual artist currently imprisoned in a California state penitentiary who has produced a series of drawings of “prisoner’s inventions.” These inventions, developed out of prison cultures, include: a cigarette lighter fashioned from salt water, wire, paper clips, a shaving razor, and tape; a camouflaged toilet paper dispenser; and salt and pepper shakers made from aluminum cans and popsicle sticks.

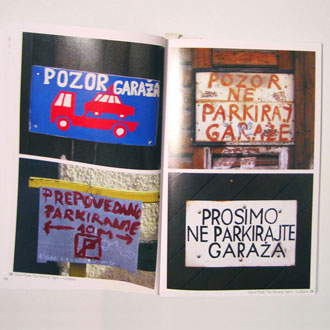

Many other projects by Temporary Services and collaborators elevate art’s use value within a particular cultural or social context. Another favorite of mine includes “Public Phenomena: Informal Modification of Shared Spaces,” a project in which the group documents “informal” uses of signage (parking signs, grave markers, neighborhood rules and regulation signs) within common spaces.

Parking regulation signs from Temporary Services' "Public Phenomena: Informal Modification of Shared Spaces" booklet. Courtesy Temporary Services and Book By Its Cover

Astounding on Temporary Services’ website is the sheer volume of materials the group has made available for public consumption and distribution. With few exceptions, the projects they have worked on—and especially their writings and ‘zines—are archived and easily accessible via PDF. This archive include over nearly ninety booklets. It also includes a labyrinthine backlisting of shows and other public events the group has participated in—a crucial archive of social networks among artists and artists’ groups of the past twelve years. What is not free can be purchased very cheaply at Temporary Services’ press, Half Letter Press, where one may find some of their books and posters, and the wonderful interviews they conduct with musicians such as Kawabata Makoto of Acid Mothers Temple and the Austin-based punk band, The Dicks. As part of their Temporary Conversations series, Temporary Services has also conducted extensive interviews with artists whose aesthetically rigorous practices may not otherwise receive recognition since they produce a social service. The include the work of Suzann Gage, whose drawings revolutionized women’s health care in the 70s, and Peggy Diggs, who was involved with the Domestic Violence Milk Carton Project of 1992 and other projects promoting women’s rights and well-being.

While I do not wish to label Temporary Services’ politics, which, like quite a few art groups currently, is not statist in nature (in other words, not directly aimed at challenging politics at the electoral or nation levels), I would emphasize the political importance of their commitments to Do-It-Yourself culture. The group discusses this commitment in an interview they gave in February of 2007 with Doro Boehme, Lindsay Bosch, and Kevin Henry. One of my favorite moments in this interview, which resounds with a remark Temporary Services made above about art making in the wake of the 90s Culture Wars, is when Marc Fischer describes a generational gap he feels towards Karen Finley and other artists of the Culture Wars generation:

I always felt that kind of generation gap…we’re not so many years removed from some of these people, but you know when those artists like Karen Finley…when their grants were rescinded? I always remember feeling like, “They were expecting money from the government to do that work?!” You know? It seemed that they were of a generation in which you used to be able to really expect that, and because of that, sure, they were really pissed off when they had their money taken away. But I always remember feeling like, “How weird that they asked for funding.” And I think that response comes out being involved with underground music and publishing. I wouldn’t expect the government to give money so the Cheetah Chrome Motherfuckers could come from Italy to play in the U.S. [laughs] Of course the government wouldn’t care. Of course they wouldn’t support it, but Karen Finley expected it?

Coming from a subculture of poetry chapbooks, music fanzines, and craft-style art projects as a teenager, I relate to the generational consciousness partially driving what Temporary Services and the group’s innumerable collaborators do. Many of them have taken matters into their own hands in the face of failures in education, administration, and distribution of resources. Underpinning Temporary Service’s DIY spirit is a more fundamental spirit of culture workers who would create new spaces in which to live, create, communicate, and educate. What Temporary Services and others are getting at—what they are engaging, critiquing, and overturning—are core values having to with the question of who and what art is for? Is it for prestige, for instance, or is it to make something happen; to instigate or activate something? Should it hang on the wall in a museum, gallery, or in the home of a private collector, or should it be something available to anyone who may wish to admit its value and presence? Can, as Temporary Services’ name suggests, art be useful? Can it be in the service of one’s community, friends, and family? Can it produce sustainable economies and infrastructures of care and well-being?

Brennan McGaffey's and Temporary Services' installation of "Audio Relay" at Lewis and Clark University's Hoffman Gallery. Courtesy Portland Art.

In this spirit, Temporary Services disseminates instruction manuals which show people how to do everything from building their own portable radio studios (Audio Relay), to recreating—and in the process demystifying the production, reception, and distribution—of works by conceptual artists such as Mel Bochner, Lawrence Weiners, and Felix Gonzales-Torres. They also produce models of curation and distribution that directly challenge the star systems which have helped to maintain the triad of gallery-museum-academy. Some of these alternative exhibition spaces include a portable exhibition space which can be installed at any moment, in any public space, providing an impromptu “gallery” of works (Free For All Re-Exhibition Strategies). Another is a work in which art works are donated by artists and then chosen and taken home by the gallery goer, “free of charge” (Free for All). This work, whose concept is simple, yields a number of complex effects since the act of choosing becomes an act of valuation. What does it mean to divest one’s self of art works? What does it mean for an audience to be able to collect “freely”? What would it also mean for these works to be exhibited on an impromptu basis, in the line at a bank or the DMV, for instance?

Yet another aspect of Temporary Services work that I would like to emphasize are its interventions into public spaces. One of the more playful of these projects involves the creation of “ravioli,” and the use of them to distribute art and cultural materials publicly (“Chicago Ravioli Project”). The ravioli, which is actually a sealed plastic bag of various sizes, allows an audience to discover art in places they might not typically; for example, along fences or attached to mailboxes. Like public space itself, the ravioli relates the space inside and outside it — what is interior and exterior, seen and unseen, permissible and not permitted, for private and public consumption.

Other projects involving intervention and explorations in public space (a problematic which could be ascribed to many of the group’s projects), include the development of giant, inflatable arms and masks that people can wear for different occasions (“Masks and Public Inflatable Projects in Puerto Rico and Chicago”). Another one of my favorites is a mail art project which involves detourning “business reply” mail at popular corporate franchises such as Starbucks so as to draw attention to the waste produced by the commonly used advertising technique (“Business Replies”).

While I know I have just scratched the service of Temporary Services here, I hope that you will check out their website, which has more content than one will probably be able to take in after numerous sittings. Please also check back on this blog next month for more 5 Questions!

Pingback: Ravioli from Temporary Services | 1 Weird Old Tip

Pingback: Center Field | Is Locale Needed? Netart in the Midwest | Art21 Blog

Pingback: 5 Questions (for Contemporary Practice) with Nato Thompson | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Open Enrollment | Work after work after work… | Art21 Blog