The day after Ball-Nogues Studio’s installation, Gravity’s Loom, opened at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, I had the opportunity to talk with Benjamin Ball and Gaston Nogues about the project. As an art conservator, I’m most interested in the physical aspects of their work, how it will be represented throughout its exhibition, and how they envision visitors interacting with it.

Richard McCoy: At most museums security guards are often in a position to inform visitors about artworks before any gallery label is read. What if anything would you like IMA security guards to discuss with visitors about your piece?

Gaston Nogues: Last night at the openin,g I spoke to about six of the IMA docents. They wanted to know all of the specific details of the construction of the piece: how many pieces of string we used, how long it is in total, and so on. I think it’s good to tell people those kinds of things. We used 30 miles (about 160,000 linear feet) of string in this installation. I’m guessing that amount of string could be used to stretch completely around the beltway of Indianapolis, to tow a boat down the entire Central Canal Towpath, or stretch from here to Broad Ripple Village and back five times.

Benjamin Ball: The work is a response to the architecture of the IMA building. It picks up on some of the latent history in the Efroymson Family Entrance Pavilion; its oval shape has precedent in Baroque architecture. We saw the Pavilion as being akin to a Baroque dome. Using the dome cornice of the Stockhausen Church in Germany as an inspiration, we interpreted and applied the geometry of the cornice as painted image to the spiraling array of strings in Gravity’s Loom. Like Baroque architecture, the installation combines the effect of architecture, sculpture, painting, and decoration.

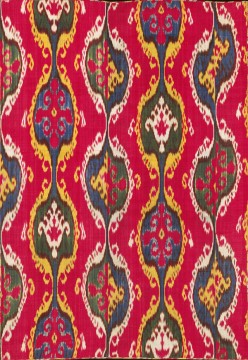

In total, there are 1824 stings and each one is slightly different. Every string has been painted and cut independently using a machine we invented and designed. The process of making the work is a kind of 21st century, 3 dimensional version of Ikat—a textile-making process that involves dying small bundles of yarns prior to them being placed in a loom and woven.

Ikat woven wall-hanging from Bukhara, Uzbekistan, mid 19th century. Image courtesy the Freer-Sackler Gallery.

Repeated bindings and dyeing, coupled with slight shifting of the yarns on the loom yields the design, which has a kind of soft “cloud” effect. It creates a kind of ephemeral and ghostly presence of the Baroque. Here, however, we have used new technology to enable us to make this Baroque-inspired cousin of Ikat in space. It is like painting in space. I would also encourage visitors to take a look at the Ikat collection at the IMA.

GN: You can think of our machine as a kind of printer, but instead of printing a sheet of paper with an image and words, our machine prints out a string with color.

RM: I’ve found that museum visitors are unpredictable—works that I’m convinced are going to be handled roughly are treated gently, and things that I think no one will touch often get handled roughly. Do you ever have a sense of how your projects will be handled?

BB: We’ve made projects for galleries that were meant to be climbed on, punched, and trekked over. We’ve also made things in festival settings that we intended visitors to directly interact with by sitting and climbing. I can’t think of a more rowdy atmosphere for a projecs than at the Coachella Festival or the Warm Up events in the P.S. 1 courtyard. Both of those environments are filled with a lot of people that are, shall we say, “having fun,” and interacting with the work in a direct way.

But with this installation at the IMA, we’re not going for that level of physical engagement. I think the work has an obvious delicacy. My guess is that people are not going to want to touch this.

GN: To break one of the strings it would take someone really, really tugging on a particular string. You’d have to be very committed to yanking one down. By the time someone started doing that, one of the guards would be all over them.

BB: Someone could touch one of the strings or flick it and it wouldn’t damage the work. But I know that if we invited or allowed visitors to do that, then the next thing we know they will be pulling on it very hard just to see what happens. So in this way, we say, “please do not touch.”

Ball-Nogues intern Claude Moussoki and Benjamin Ball examine "Gravity's Loom." IMA photo by Hadley Fruits.

RM: As an art conservator who is constantly trying to protect artworks, I can’t help but just say thanks for saying do not touch!

GN: When we created this piece at the IMA, we weren’t trying to create a tactile experience. It’s a work that choreographs movement, but it is not intended to be touched.

BB: This piece couldn’t be more ephemeral and delicate when, for example, compared to Rip Curl Canyon, which we completed at the Rice Gallery in 2006.

That installation was very different; it had a very different set of considerations that went into its making. In the Rice Gallery piece, we wanted patrons to climb on it, but in this one we say, “look but do not touch.” So with Gravity’s Loom, you can climb under it, even lay down underneath.

In a perfect world, people would restrain themselves, and it would be great to let people touch Gravity’s Loom, but the problem is that some people have low impulse control so the little touch quickly becomes someone pulling on a string and breaking it.

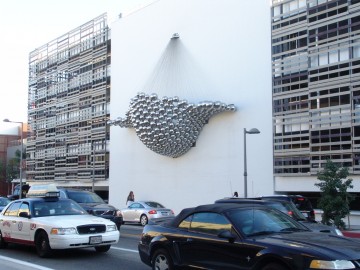

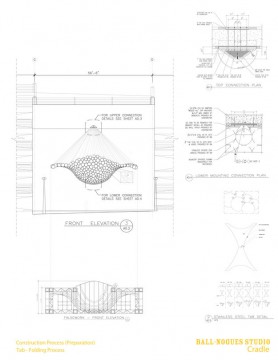

RM: This installation was specifically designed for the Efryomsom Family Entrance Pavilion here at the IMA. After about 6 months, it will be taken down and some of the materials returned to you. By comparison, your recent installation in Santa Monica, Cradle, will be up permanently. How do you approach your choices of materials relative to the duration of an exhibition?

GN: Our approach is to address all of structural concerns first. Cradle, is made out of 316L stainless steel, which is a heavy-duty material. We made the sculpture out of material that is appropriate for the environment. We made all of that piece out of the same metallic alloy and all of it had the same finish, including the welding lines, which were also polished to the same finish.

When we started with the idea for that project, at first we saw the balls as a commodity, as something you could buy at a garden store—“gazing” globes. We weren’t interested in fabricating them ourselves; we were more interested in purchasing something and then using the product as is.

BB: There were some economic calculations involved in that. As Gaston said, we knew that these spheres would be available, that somebody would be manufacturing them somewhere in the world, and that we could get them in sufficient quantities. We also knew that there would be a relatively low degree of tolerance in their manufacture. We were looking for a standardized part, a thing that wouldn’t vary too much. Having said all of that, we weren’t interested in a particular material: we examine every project on a case-by-case basis and find what fits the situation.

GN: For the project at the IMA, we’re interested in being able to see more, to see what the strings will do over time. Will they stretch over time? I’m curious if they will actually droop down over the length of the exhibition. At the same time, I’m interested in knowing if the colors will be faded after six months because they are exposed to direct light coming through the windows. All of this information is important to us and we’ll use it when we are making our next project.

RM: In your recent interview on designboom, you talk about your interest in watching shows like “How It’s Made.” I love that show too, but I also like to learn how artists make their work. So of course I liked the the video MOCA made for you, “The Making of Feathered Edge.” Some artists don’t like to reveal their process to this level, but architects and designers seem to have a different approach to process; they seem to be more open. Can you talk about your interest in sharing information around your process?

GN: We work with a lot of people. I’ve always worked that way. I’ve worked in environments that had a lot of outside consultants and on projects that have a lot of people involved in making something. So maybe it’s that kind of exposure. For example, when I was helping to build one of Frank Gehry’s buildings, I learned that you have to work with a lot of people and you have to be willing to share your vision.

BB: It becomes almost impossible to control the dispersal of information. In our case, we do have consultants who have somewhat of a stake in our projects—and we could clamp down on that and require that they not reveal anything. But a lot of our projects are done with a spirit of cooperation.

In spite of the fact that it might seem as if we reveal a lot of our process, there’s a lot of things we’ll never reveal. One way of looking at the work is through a lens of critical craft—where there is meaning behind the making. But we also conceive of the works in a more aesthetic and experiential sense, independent of making. We understand them in terms of how they effect one’s navigation through space, like architecture, and how one perceives the building itself relative to the work. We want our installations to operate on several levels.

GN: People occasionally call and ask questions about how we’ve made a particular thing that we’ve spent a lot of time researching and experimenting with. We’re not so willing to share all of our information because in the end you have to learn for yourself otherwise it’s like, why do it?

BB: Our projects have a kind of rhetorical aspect to them. We’re saying within the design discourse that the process by which something is made determines or influences the outcome and that the making and production process is meaningful.

The invention of a process becomes an avenue toward pushing into new territory with respect to form making, space making, and what a work can signify. When you’re thinking in architectural or spatial terms and at this scale, structure and material influence what you can and cannot do and the kind of spaces and form you can create.

Pingback: Considering Gravity’s Loom: A Discussion with Ball-Nogues / Art21 Blog « word pond